Ono City, located in the northeastern part of Fukui Prefecture on the border with Gifu Prefecture, is blessed with a climate of widely varying temperatures and subsoil water from the foot of Mount Hakusan, making it the third largest rice producing area in the prefecture. Masayuki Matsuda, the owner of Shirobei, a natural rice farmer who insists on using no pesticides or fertilizers, won the highest award in a rice competition. What is Mr. Matsuda’s commitment that produced this rice?

Oddball from Small Rural Community in Fukui Prefecture Wins Top Prize in Rice Competition

The Morime district of Ono City, Fukui Prefecture, where Mr. Matsuda lives, is a small community of 45 households, 40 of which are engaged in traditional farming. In 2006, he began growing rice naturally, without using pesticides, fertilizers, herbicides, or fungicides, in a pristine environment. Currently, 2.5 hectares of the 3.2 hectares of rice paddies are used to grow naturally grown rice varieties such as Akisakari, Himegomomi, Milky Queen, Sasanishiki, Asahi, and Nikkomaru. Weeding is kept to a minimum and no animal manure or other fertilizers are applied in order to keep the environment close to that of the wild. However, in 2015, its rice won a gold medal in the most difficult overall category at the National Rice and Food Taste Analysis Competition International, the largest rice fair in Japan, and has won gold medals and special excellence awards in various categories to date.

Akisakari” has its roots in ”Koshihikari

Koshihikari,” Japan’s representative rice, was actually born at the Agricultural Experiment Station in Fukui Prefecture. It has a large grain size, sweetness, and a rich aroma when cooked, and is harvested in large quantities. It is now grown all over Japan as a representative of delicious rice, and Fukui accounts for 70-80% of the rice harvested in Japan. However, due to the effects of global warming, the temperature during the “ripening period,” when the ears of rice emerge, blossom, pollinate, and the rice grows and enlarges, has become too hot, resulting in a deterioration of rice quality, known as “high temperature injury. In 2008, Fukui Prefecture developed the “Akisakari” variety as a countermeasure against high temperature damage. Having its roots in Koshihikari, it is tolerant of high temperatures and has a late maturation period to avoid high temperatures as much as possible. It is characterized by its slightly chewy texture, and the more it is chewed, the sweeter it tastes.

After trying it, I felt that Akisakari was the best for the region.

Mr. Matsuda began growing Akisakari right around the time it was announced. In 2012, an acquaintance secretly entered Mr. Matsuda’s Akisakari rice in a rice and taste evaluation contest. Although it did not win an award, it was highly praised, and he began growing it in earnest, thinking that he could produce rice that would win awards. The following year, he was certified as the “BEST FARMER” in the same competition, which received approximately 5,000 rice samples , and the selected Akisakari rice received the Environment Kingdom Special Excellence Award in the special cultivation category. Mr. Matsuda’s award was narrowly chosen based on the sum of his scores for eating quality, which is measured by an analyzer to measure moisture, protein, amylose, and fatty acids, and taste quality (miduchi), which measures the umami component of white rice.

Concerned about his family’s health, he moved to safe cultivation methods that do not use pesticides.

Mr. Matsuda insists on being recognized in competitions because he wants the people around him to understand the value of his naturally grown rice. He became ill after his son, who was spraying pesticides with him, inhaled them and collapsed. Concerned about his health, Mr. Matsuda began to teach himself how to grow rice without pesticides, recalling his childhood experience of growing rice using cow manure as fertilizer when his father ran a dairy farm. The rice harvested at that time was so beautiful and clear that it won the second prize in an evaluation by an agricultural cooperative, which was rare at that time.

Miracle apples” sparked a strong interest in natural cultivation

As he gathered more information, he came across the book “The Miracle Apple,” which was also made into a movie, written by Akinori Kimura, who is known as a charismatic figure of natural farming. He became interested in the natural way of farming, and began to attend seminars and workshops on natural farming around the country on weekends and with his salary. What surprised me the most was that when I put freshly cooked rice in a jar with the lid on, it fermented and smelled good. Organic rice was just going to rot and turn to mush,” he said. This was the farming method I was looking for, and I decided to spend the rest of my life on it,” said Matsuda.

Year after year, he realized that it is difficult to cultivate rice in soil accustomed to chemical ingredients.

Rice grown under the cover of the surroundings was highly appreciated.

The first year they started growing rice without pesticides, fertilizers, or fungicides, they were able to harvest four bales per square meter of rice paddies, half of what they had been able to produce with pesticides and chemical fertilizers. The following year, however, the harvest dropped dramatically to only one bale. Seeing the rice paddies overgrown with weeds, his relatives were furious, saying, “We have gone crazy because we do not use pesticides and fertilizers. Mr. Matsuda believed that the problem lay in the soil soaked in chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Unable to overcome the many voices of opposition, such as, “If weeds grow, diseases and insects appear, it will cause trouble in the surrounding rice paddies,” he suspended pesticide-free, fertilizer-free, and fungicide-free cultivation. However, Mr. Matsuda was not ready to give up and decided to continue cultivating only one field in secret. As a result, the rice harvested from that one acre was recognized in a prestigious competition, which changed the attitude of those around him, and Mr. Matsuda gradually expanded his naturally cultivated acreage.

After decades of using chemical fertilizers and pesticides that became widespread after World War II, the soil is not easily restored to its natural state. It is important to remove the chemical components by digging the rice fields deeper to expose them to the air and by using the power of plants with deep roots, such as wheat, to take care of the soil. Even after 16 years of doing so, the weeds are finally getting under control. It will take more time,” said Matsuda, crushing the weed-covered soil with his fingers.

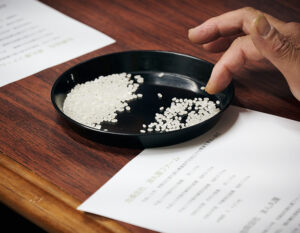

He is taking analytical data to “visualize” his pesticide- and fertilizer-free production.

Nevertheless, when I go out to the rice paddies now, I feel that the environment is gradually returning to the way it was in my childhood, with more snakes and frogs, and ducks flying in and out. The yield is still unprofitable, at most about 4 bales per hectare. There was a time when I tried to increase the planting density while checking how the rice was growing. He has also tried to make the rice fields more attractive to ducks, which eat weeds, by repeatedly flooding the fields with water. He is continuing his research by collecting rice data (data on amylose, which determines the viscosity of rice when cooked, and other quality data) for each rice paddy, which he will use for the following year’s cultivation.

In addition, in order to add value and increase the price per bale, they have asked the Tsukuba Analysis Center to measure residual pesticides and radiation to confirm safety. They also measure data on the analysis of brown rice components such as protein, carbohydrates, and sodium, and disclose this information when offering the rice as a tax return gift to hometowns and for publicity purposes.

How do you convert the evaluation of rice into needs?

Another thing that Mr. Matsuda is trying to do is to store the rice after harvesting. He keeps the brown rice in a cool storage at 12°C to ensure that the taste value does not change. He says that even one year after harvest, the taste of such rice does not deteriorate to the point where one cannot tell that the rice is old. If the rice is stored well, it does not oxidize and turn yellow, and it can be eaten for a long time,” he says.

When a tasting event was held at a local community center, Mr. Matsuda’s rice was rated as the best tasting rice compared to the same variety from other regions. However, even with such a reputation, when the price was discussed, rice stores and mass merchandisers would not take it up. The challenge for the future, he says, is how to turn the reputation of the rice into a need, and to get consumers who buy the rice once to become repeat buyers.

What is the true rice that Mr. Matsuda is aiming for?

Mr. Matsuda’s goal is to produce rice that has been grown without too much human intervention, that adapts to the local environment, and that has characteristics unique to that area. Many modern rice varieties are supposed to be grown with an abundance of fertilizers and pesticides. He is looking forward to seeing how such rice will explore cultivation policies and change its flavor in response to his own cultivation methods that are being evaluated.

It is said that when rice is grown naturally, it eventually becomes closer to the original species. Modern rice has a strong aroma when cooked and taste when you put it in your mouth, and many varieties of rice play a leading role in their own right. My rice is grown as it is, which I believe makes it closer to the original form of the plant called rice. I think it will be rice that is the star of the show, but not the main attraction, and not too tasty that it complements side dishes. Rice is a staple food, and Mr. Matsuda believes that it should not have too much individuality in order to keep eating it for a long time without getting tired of it.

I want to create a healthy Japan with naturally grown rice.

I want to keep my philosophy in mind,” he says, ”because if you only learn how to cultivate rice, you are just imitating others and will fall behind . When he looks at the condition of his rice paddies and the yield of his harvest, he almost fails many times, and every time he does, he remembers his starting point, his philosophy. Natural cultivation is so difficult and unprofitable considering the time and effort involved that only a few people engage in it.

Since they do not use herbicides, most of the 2,500 hours of annual farm work is spent weeding and mowing. He is absolutely confident in the taste of his rice, saying, “ If only there was a chance for people to try our rice once.” He is passionate in his words, saying, “I want to create a healthy future for Japan with strongly grown rice,” while adding value through competitions and analytical data based on his particular farming methods, which he started because of the health of his family.