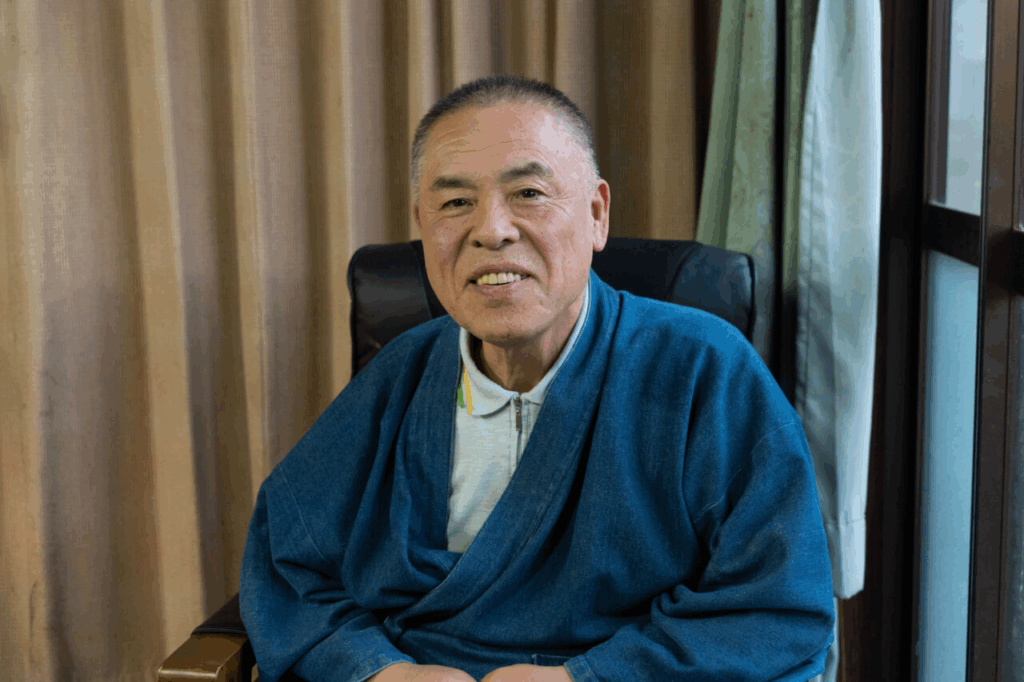

Located almost in the center of Fukui Prefecture is Sabae City. In the mountainous eastern part of the city lies the Kawada district, a center of traditional lacquerware production in the Echizen region. Here, traditional techniques that have been passed down for 1,500 years are being combined with modern designs and functionality to create lacquerware for the contemporary lifestyle. One of the pioneers of this movement is Atsuo Yamagishi, who created lacquerware that can be used casually at the dinner table every day, with even scratches adding to the charm of the piece.

Echizen lacquerware is typically made by craftsmen who divide the work among themselves. Why is it made by families?

At its peak, Echizen lacquerware accounted for 80% of the domestic market share for commercial lacquerware. The history of lacquerware in the Kawada district, where it is produced, dates back 1,500 years, and the production of lacquerware is still carried out today by specialized craftsmen working in a division of labor. As a result, even today, there are many lacquerware wholesalers and craftsmen’s workshops in this town of about 4,000 people. Atsuo Yamagishi not only creates lacquerware but also produces lacquer artworks commissioned by galleries and other clients. His workshop, “Kinju,” is located in the mountains, a short distance from the town center.

Currently, the workshop’s signature lacquerware items are produced by Yamagishi’s son, Yoshiji, who has taken over the business, with the production process divided among family members, from the base coat to the final finish. The reason they produce everything in-house is that the technique used by the Yamagishi family is unique, making it difficult to outsource to other workshops.

When one hears “lacquerware,” one might typically imagine red or black bowls with a glossy finish. However, Yamagishi’s bowls feature brush strokes visible on the surface, giving them a slightly textured feel. They also have a warm, wooden texture and a unique shape that fits comfortably in the hand. Compared to the traditional lacquerware made in the Kawada region for use in inns and restaurants, the distinctive features of Yamagishi’s bowls are that each one has a unique expression and that they are designed so that even if the lacquer gets scratched from daily use, it doesn’t matter.

We hope that people will use these lacquerware pieces, which require careful maintenance, in their daily lives at home.

At its peak, Echizen lacquerware accounted for 80% of the domestic market share for commercial lacquerware. The history of lacquerware in the Kawada district, where it is produced, dates back 1,500 years, and the production of lacquerware is still carried out today by specialized craftsmen working in a division of labor. As a result, even today, there are many lacquerware wholesalers and craftsmen’s workshops in this town of about 4,000 people. Atsuo Yamagishi not only creates lacquerware but also produces lacquer artworks commissioned by galleries and other clients. His workshop, “Kinju,” is located in the mountains, a short distance from the town center.

Currently, the workshop’s signature lacquerware items are produced by Yamagishi’s son, Yoshiji, who has taken over the business, with the production process divided among family members, from the base coat to the final finish. The reason they produce everything in-house is that the technique used by the Yamagishi family is unique, making it difficult to outsource to other workshops.

When one hears “lacquerware,” one might typically imagine red or black bowls with a glossy finish. However, Yamagishi’s bowls feature brush strokes visible on the surface, giving them a slightly textured feel. They also have a warm, wooden texture and a unique shape that fits comfortably in the hand. Compared to the traditional lacquerware made in the Kawada region for use in inns and restaurants, the distinctive features of Yamagishi’s bowls are that each one has a unique expression and that they are designed so that even if the lacquer gets scratched from daily use, it doesn’t matter.

We hope that people will use these lacquerware pieces, which require careful maintenance, in their daily lives at home.

Mr. Yamagishi was born into a family of lacquer artisans that has been passed down for generations, and he inherited the techniques from his father as the fifth generation. In his mid-20s, when he exhibited his work at an exhibition outside the prefecture, he noticed that the questions from customers were not about the beauty of the lacquerware’s design, but rather about how to use it at home and how to maintain it on a daily basis. “Perhaps people think that hand-painted lacquerware like ours is difficult to use in everyday life,” he thought.

Originally, lacquerware was used on special occasions such as weddings and funerals, so it may be considered too delicate for everyday use. The beautiful, jewel-like luster may also make people hesitant to use it, fearing they might scratch it. With this in mind, Yamagishi began researching lacquer itself with the goal of developing durable lacquerware that could be used without hesitation in everyday life.

When he went into the mountains to collect lacquer sap (the process of extracting sap from lacquer trees), he discovered that the raw lacquer sap, which has a whiskey-like brown color, hardens into a stone-like substance that cannot be scratched even with a fingernail. However, when trying to enhance the durability of the vessels by applying multiple layers of lacquer to the wood, the lacquer became prone to cracking and peeling due to impact.

Upon researching literature on lacquerware, I learned that to make the vessels less prone to cracking and the lacquer less prone to peeling, the “wood base” (the raw, unfinished wood) is more crucial than the “coating.” By using a technique called “wood hardening,” which involves allowing the wood to absorb a large amount of lacquer, the wood itself becomes harder, improving the adhesion of the subsequent base coating. When I actually made vessels using this method, customers reported that the time before they needed repairs was significantly extended, and some pieces could be used for over 10 years without maintenance.

As a lacquerware artist from Echizen, it took time for Yamagishi’s dedication to be accepted.

To further enhance the strength of the base, the coating liquid was mixed with ground lacquer powder and grinding powder to achieve the optimal composition. While the durability was satisfactory, there were some issues. Typically, lacquer used for coating is filtered before application to remove impurities and prevent brush marks from remaining. However, since Yamagishi’s lacquer already contains powder, brush marks inevitably remain. Nevertheless, the texture created by these brush strokes adds character to the lacquerware’s surface, making any scratches less noticeable. For the final finish, the surface of the completed piece was sanded with sandpaper and intentionally given a matte finish to mimic the worn appearance of aged lacquerware. This was an innovative twist on the then-popular trend of intentionally washing new jeans to create a worn look.

At the time, the bowls that Yamagishi-san had designed were handmade with a strong sense of craftsmanship, with brush strokes still visible. It was vastly different from the neatly shaped lacquerware now lined up in the workshop, so when the local artisans, including Yamagishi’s family, saw the bowl he brought, they strongly opposed it, saying, “Are you trying to sell such poorly painted work?” When he asked a relative to handle the next step in finishing the bowl, they responded, “Can you really make something like this?” and kicked the box containing the bowl, leaving him feeling humiliated.

Despite this, Yamagishi persisted, relying on family members who understood his approach, and managed to complete the piece. He immediately took it to a local wholesaler, but the concept of accepting imperfections was too radical, and no one was willing to place an order. Yamagishi then leveraged the connections he had built through previous events to exhibit his work at events and retail stores nationwide.

These one-of-a-kind Echizen lacquerware pieces grow more beautiful with use.

After holding several solo exhibitions at a friend’s shop, Yamagishi’s innovative and unconventional tableware designs gradually gained recognition. One day, after being featured in the magazine “Katei Gaho,” inquiries began pouring in from pottery shops and galleries across the country. Typically, handmade pottery, which emphasizes its natural texture, is considered difficult to coordinate with traditional lacquerware due to their differing styles, especially when placed on the same table. However, the craftsmanship of Yamagishi’s vessels and plates makes them easy to pair with traditional ceramics.

They also complement the works of other ceramic artists with strong individual styles, blending seamlessly when placed together on the same table. For example, when pairing a ceramic cup with Yamagishi’s lacquerware as a saucer, the rough texture of the ceramic bottom does not leave noticeable scratches on the lacquerware. Yamagishi’s “casual lacquerware” steadily gained popularity, leading to solo exhibitions across the country. In 2005, he had the opportunity to hold solo exhibitions and lectures at four locations in New York City, and he continues to hold exhibitions at department stores and galleries in Tokyo several times a year.

As he pursued techniques that left brush strokes visible, Yamagishi encountered “negoro-nuri,” a traditional Japanese lacquering technique originating in Wakayama Prefecture. This technique involves applying a base coat of black lacquer and then layering red lacquer on top. As the piece is used, the red base gradually becomes visible through the black surface. He also incorporated the “Asahi” technique, also known as “gyaku negoro,” which involves applying black lacquer over a red lacquer base, causing the red to gradually emerge from the black surface with use. This expanded the range of his artistic expression.

For woodworking, he uses the “mokkan-shiki” method, which involves solidifying wood powder and soaking it in a large amount of lacquer to create a stronger base. This wood base does not warp or crack even after drying, allowing it to be used for many years and fully enjoying the natural aging of the vessel. “Even if a family purchases several of the same bowls, each one will develop its own unique character depending on who uses it.” These vessels are truly created into one-of-a-kind pieces by the people who use them.

The original beauty of Fukui’s traditional Echizen lacquerware, infused with a modern sensibility.

Additionally, since he began holding solo exhibitions, Yamagishi has been actively engaged in creative activities that incorporate traditional techniques with a modern sensibility in lacquerware and lacquer-based works.

In the past, he created colorful lacquerware items such as cups, plates, and chopsticks for national touring exhibitions as an artist. However, after falling ill several years ago and finding it difficult to work with his right hand, he decided to focus on painting, which can be done without using his right hand. He began creating one-of-a-kind pieces by using the back of jackets, wooden panels, and washi paper as canvases, freely expressing his ideas. In the past, he would have his wife hold the vessels or press down the paper, but now he fills a bowl with water and uses cloth or paper as weights to create pieces on his own. “I’m challenging myself to see how far I can take my work using only my left hand, immersing myself in my own world,” he says with a smile.

His current favorite piece is a work in progress called “rough carving,” where lacquer is applied to the sturdy material of a vessel cut from wood. He feels a sense of vitality in the roughness of the material before it is carved.

In the lacquerware industry today, new combinations and techniques that were previously unimaginable, such as applying lacquer to resin, are emerging. “There are still so many things I want to try,” says Yamagishi. The lacquerware and lacquer art he has created are at the heart of this movement, serving as wings that carry the culture of lacquer and creating hints for the future survival of the Kawanoda region.