With the globalization of food culture, the Japanese diet has undergone rapid changes. The annual per capita consumption of rice in Japan has continued to decline since 1962, finally reaching less than half of its peak in 2020. As the Japanese food culture has declined, sake, which has been enjoyed along with Japanese food, has also been on the decline, being pushed aside in favor of beer and wine. As the market shrinks, simply following the old style will lead to decline. Naotaka Miyasaka, president of the long-established brewery Miyasaka Brewery in Suwa City, Nagano Prefecture, and his son Katsuhiko, also struggling between tradition and respect, have begun a new challenge without giving in to adversity.

Miyasaka Brewery is located near Lake Suwa, the largest lake in Shinshu, and is widely known for its 360-year-old sake called “Masumi,” which is derived from “Masumi no Kagami,” a mirror used at Suwa-taisha Shrine, famous for the Omihashira Festival. The company boasts the largest production volume in Nagano Prefecture and is a nationally renowned sake brewer, but its journey has not been an easy one, according to Katsuhiko, the next head of the company.

History of Miyasaka Brewery

The original Miyasaka family was a vassal of the Suwa family, which ruled the region until the Warring States period. Tossed into the war between Takeda and Oda, they put down their swords and embarked on the sake brewing business. However, as times changed from the Meiji to the Taisho era, and the brewery’s business became difficult, the family switched to miso brewing. Instead, Masaru Miyasaka, the great-grandfather of Katsuhiko Miyasaka, was entrusted to take the helm of the sake brewing business.

Masaru Miyasaka, who was in his 20s at the time, focused on improving the quality of the sake he brewed, dreaming of one day creating the best sake in Japan with other toji of the same age. In 1943, Miyasaka Brewery finally won first place in the National Sake Competition. The company went on to win awards at other prestigious sake competitions, and Miyasaka Brewery, an obscure sake brewery in Shinshu, was thrust into the limelight.

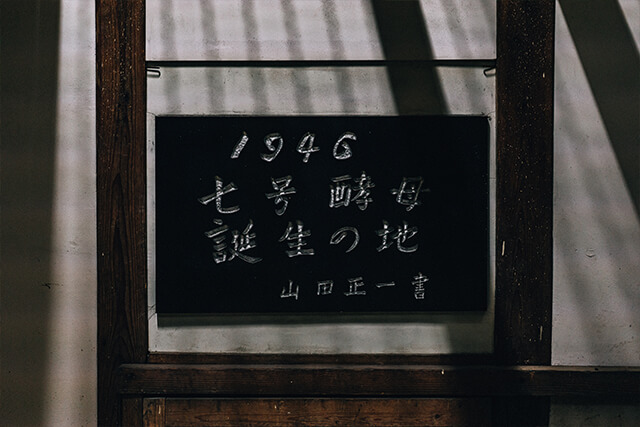

The “No. 7 Yeast” that supported the brewery’s breakthrough

The reason for Masumi’s great leap forward was due in large part to the brewery’s proprietary yeast, “Shichi-go Yeast,” which was eventually recognized as a superior yeast.

Masumi, which repeatedly won top prizes, attracted the attention of many researchers, and as a result, Dr. Shoichi Yamada of the Ministry of Finance’s Brewery Research Institute, the highest authority at the time, visited the brewery to inspect it. This alone was an honor in itself, but after carefully inspecting every corner of the brewery, Dr. Yamada discovered a new type of yeast in the fermenting mash. This was Miyasaka Brewery’s brewery yeast, later named Shichi-go Yeast.

Yeast is a type of fungus used in the fermentation of sake. It is so important that it is said to have a greater influence on sake than rice, especially in the production of aroma components and acidity, which are related to flavor. At that time, there were still many sake breweries that used wild brewer’s yeast, but wild yeast was an unstable fungus that carried risks such as contaminating the brewery.

On the other hand, this No. 7 yeast has stronger fermentation power than conventional yeasts and can ferment even at low temperatures. It is characterized by a clear taste and a gorgeous orange-like aroma, and has less off-flavor that can be produced by high-temperature fermentation. The No. 7 yeast, which has brought a breath of fresh air to the sake industry, was brought back to Japan by Dr. Kikuchi and distributed as “Kyokai Yeast” to sake breweries throughout Japan. The widespread use of Shichi-go Yeast led to an improvement in the quality of the entire industry and contributed greatly to the production of safe and delicious sake. Even today, more than 70 years after its discovery, Shichi-go Yeast is said to be used in more than half of the nation’s sake breweries, and is still enjoyed by sake drinkers.

From Japan to the world. Sake brewing with a global perspective

Anticipating the coming of a new era, Miyasaka Brewery pushed ahead with its expansion into Tokyo. After graduating from Keio University and studying abroad at Gonzaga University in Washington State, the current president Naotaka joined the company in 1983, and began using his study abroad experience to expand overseas sales channels around 2000. In this way, Miyasaka Brewery has continued to produce sake that is in tune with the times, always reading the times and looking ahead to the future.

And now, in 2019. In the new era of the Heisei Era and the 2025 Era, Miyasaka and his son Miyasaka have undertaken a reform. It was a major shift in the brewery’s approach, a return to its roots, to use only the No. 7 yeast, which is synonymous with the brewery’s own yeast.

Switching to the No. 7 yeast yeast

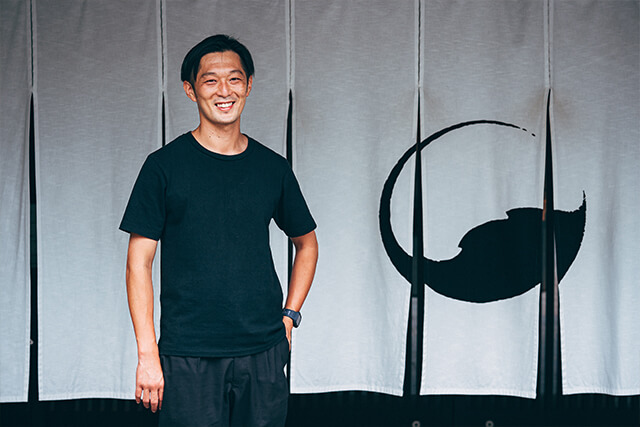

Katsuhiko, who currently serves as the president’s office manager, worked in apparel at a famous Tokyo department store after graduating from university before leaving in 2013 to join the brewery.

However, the sake industry had already begun to diversify, and following trends was no longer the only “right” thing to do. Sake itself has stepped out of the traditional ring and established itself in the world as a “SAKE” along with wine and beer. Katsuhiko felt that in order to compete in this layer, it was necessary to further express his own individuality and attractiveness and “make sake that is different from others. He saw the value in specializing in a narrow field. In 2019, he launched a project to create a new line under the two themes of “individuality unique to Miyasaka Brewery” and “high quality food sake that enhances the flavor of food.

However, it was said that it was difficult to produce a gorgeous flavor with the No. 7 yeast. It took many prototypes and a considerable amount of time to achieve the desired flavor and aroma. Even after the taste was confirmed, it was not easy to unify all the sake brewed with the No. 7 yeast. Sometimes, they even used hints from sake breweries outside of the prefecture.

The four sake products that were released were named “Shinju-AKA,” “Urushukuro-KURO,” “Hakumyo-SHIRO,” and “KAYA. Miyasaka Brewery is proud to have created these sake products through a process of trial and error, so that they can be served with any dish at today’s varied dining tables.

Launched in 2019, this series is appealing for its beautiful water and cool breezy taste of the Suwa region. The rebranding of “Masumi” is an excellent realization of Katsuhiko’s vision of “sake that adds color to the daily dining table. The idea of returning to the basics and innovation was a unique expression of the appeal of the No. 7 yeast.

Miyasaka Brewery’s goal for “Masumi from now on

Miyasaka Brewery, which began to develop products specializing in No. 7 yeast with the aim of entering the global market, also changed its symbol mark to coincide with the rebranding. The company created a simple, sophisticated logo of “a single ivy leaf reflected in a water mirror” from kanji, a powerful and dignified image that is typical of Japanese sake.

Ivy is the family crest of the Miyasaka family. The ivy has been a symbol of prosperity since ancient times. The shape of the ivy leaves reflected in the water mirror and sake cup represents the harmony of the brewer’s philosophy of “harmony, brewing, and good sake,” as well as the circle of the brewery. The duality of tradition and innovation contained in the brand message of “connecting people, nature, and time,” the gentle and harmonious flavor of the No. 7 yeast, and the desire to promote sake culture around the world are all expressed in the symbol.

Incidentally, the symbol mark was chosen for the rebranding so that people overseas who cannot read Japanese will remember Miyasaka Brewery’s sake. We believe that a universally recognized symbol will serve as a bridge to spread Miyasaka Brewery’s sake throughout the world.

Katsuhiko also says that expanding overseas is not only a way to promote sake, but also “an opportunity to reevaluate the value and characteristics of sake and to reaffirm its recognition. For example, when approaching an overseas city where Miyasaka Brewery is barely known, the sake from their own brewery needs to be explained from scratch. Each time, he says, he has to verbalize and explain the brewery’s sake, which in turn deepens his own understanding of Masumi and, by extension, Japanese sake.

When they were looking at overseas expansion and seriously trying to compete on the same layer as the great sake breweries overseas, they strongly felt that inspection visits alone were not enough to gain the knowledge needed to do so. Interaction through business will lead to deeper exchanges and learning.

Compared to wine and beer, the sake industry was like an isolated country. On a global scale, wine has a circulation of 2 trillion yen, while sake still has only about 45 billion yen. The goal for sake in the future is to become a sake that can compete with wine in the global market. Katsuhiko says he hopes Miyasaka Brewery will be able to play a part in this goal. His eyes are already filled with a sense of self-awareness and dignity as the next head of the company.