Seikichi Hasegawa is the son of his father, Shunko Hasegawa Ikkosai, a tea ceremony metalworker in Nagoya, and is the fourth generation to succeed him. At first glance, his metalwork tea ceremony utensils may seem simple, but the intricate detail and design give them a striking beauty. In addition to making tea utensils, he also works on elaborate reproductions of “disposable industrial products. We asked him about the true meaning behind his unique creations.

Born into a family of traditional tea ceremony metal workers in Aichi Prefecture

In a quiet residential area in Showa Ward, Nagoya City, a gate with a Japanese flavor suddenly catches the eye. Beyond the gate stands a Japanese-style house where Seikichi Hasegawa, who is heir to a family of tea ceremony metalworkers, carries out his work. Mr. Hasegawa’s family was a Tsubajishi for the Owari Tokugawa family, who succeeded the feudal lord of Nagoya in the Edo period, and his name has been Ikkosai for generations. During the Edo period, he used to make tsubas for sword accessories, but after the Meiji Restoration (1868-1912), sword manufacturing went into decline due to the ban on sword belts. The family then began to make metal tea ceremony utensils by utilizing their skills in processing tsubas, and these skills have been passed down through the generations to the fourth generation, Mr. Hasegawa.

In the Edo period (1603-1867), the Owari Tokugawa family popularized the culture of enjoying tea in Nagoya. This culture is still alive in Nagoya today. As a result, there are many people who enjoy tea and many wagashi (Japanese confectionery) shops. As a result, the local culture has deeply influenced the Hasegawa family’s business.

What are metalwork tea ceremony utensils?

By the way, when we think of tea ceremony utensils, many people probably first think of matcha bowls made of pottery such as Bizen and Hagi. Metalworkers work on pouring hot and cold water into tea containers and confectionery vessels used to decorate tea cakes. In other words, they play a supporting role in tea ceremony utensils. Considering this, Mr. Hasegawa says of his metalworking tea utensils, “I think it suits me to produce them in a more subdued manner, taking a step or two back, in harmony with the pottery.

However, as he immersed himself in this world, Hasegawa also realized that “making only tea utensils was not enough to fully express the skills he had honed and to develop himself and his house,” and he decided to take advantage of the skills he had cultivated to create artworks.

After studying in London, he returned to Japan to take over the family business.

It was probably his experience as an exchange student that led him to think of taking over the family business. After graduating from high school, he went to London to study sculpture for two years.

He says, “Although metalworking and tea ceremony utensils are different genres, I learned a lot in London that I am still using today. Indeed, Hasegawa’s works have a stateless atmosphere that is somehow exotic, even though they are tea ceremony utensils.

After returning to Japan, Hasegawa learned his skills under his father, but when it comes to his own works, he says, “I want them to reflect the times in which they were made. Living in the current era, he has seen, heard, and thought about many things, and his life has unconsciously influenced his work.

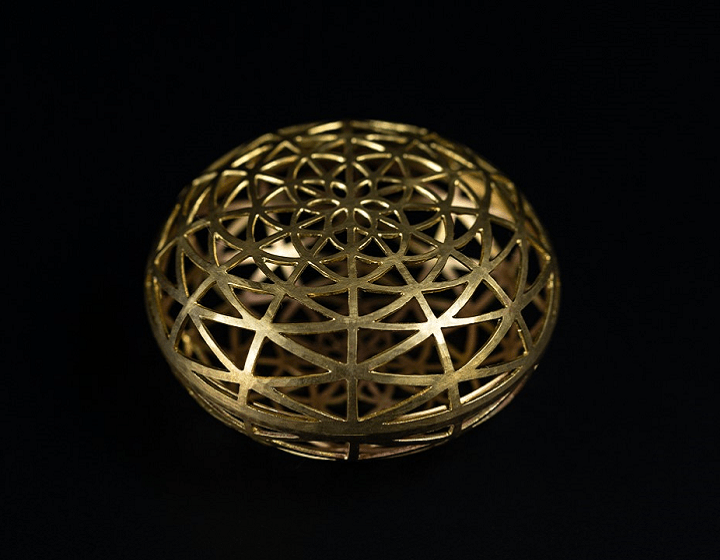

The style of Hasegawa’s work is one of his charms. He has mastered the techniques handed down from generation to generation, but he is not bound by traditional Japanese design, and has had contact with a variety of objects, including foreign jewelry and church decorations, and has flexibly fused his sensibilities.

Metal for “disposable industrial products.”

Mr. Hasegawa, who actively incorporates techniques that are not part of the traditional metalworking format, next turned his attention to “disposable industrial products. These are not tea utensils, but so-called works of art. For example, cans, paper bags, and bubble cushioning materials, also known as “petit pouch,” are elaborately reproduced in metal. Because these materials are so far removed from metal, they require a great deal of skill to reproduce elaborately, making them worthwhile to make.

In the world of tea ceremony utensils, flowers, plants, and living creatures are often used as motifs, and their organic forms and lives are often incorporated into the artwork, but for the artwork, he dared to choose inorganic objects as the subject matter. He explained the reason for this: “I reproduce disposable industrial products through metalworking. The more time and effort I put into it, the less meaningless it seems, but I quite like that feeling. I quite like that feeling,” he says, smiling wryly.

Tea utensils on display at an exhibition

He would not release an artwork based on the motif of “disposable industrial products” to the world if he felt that it was not a work of art. With this in mind, Mr. Hasegawa quietly continued the detailed and painstaking work, which seemed daunting. When he looked at the completed work objectively, he felt it was safe to present it to the world as a work of art. When he mixed it with tea utensils and exhibited it at an exhibition, he was pleased with the response from visitors.

Although the work had no use like tea utensils and was simply a piece of art, people were interested in it, saying, “That’s a unique piece,” and they were amused, saying, “What are you making? The appeal of the works reached not only those who were interested in the world of tea ceremony and tea utensils, but also those who had never had contact with the world of tea before, and many comments were received.

With this opportunity, Mr. Hasegawa decided to continue the “disposable industrial products” series in parallel with the tea ceremony utensils, increasing the number of variations of his works. Later, he expanded his scope as a goldsmith by exhibiting his work in exhibitions with the theme of “superb craftsmanship” that transcended the boundaries of tea ceremony utensils.

Having Two Axes Makes Me Feel Easier

The fact that he now works not only in the family business but also in artwork has eased Hasegawa’s mind. Tea utensils are designed with a slight pull back while considering the push and pull with pottery. On the other hand, the “disposable industrial product” series allows him to create as much as he wants. Even though they are the same metalworking, these two completely different directions make the production of each more enjoyable.

While meeting and talking with clients and visiting private exhibitions are also important parts of his job, Hasegawa says that working quietly in his workshop is more to his liking. During the daytime hours when natural light is available, he works at a brisk tempo, tapping and shaping metal, while at night he listens to the radio and devotes himself to detailed work with localized light. Day and night, he faces metal with sincerity and sometimes a sense of fun.