Kota Nakamura is the fourth generation of “Edo Kumihimo Tadashi Nakamura,” a 130-year-old kumihimo (braided cord) workshop, and is a Chiba Prefecture-designated traditional craftsman who mainly makes hand-knitted obi-jime and haori cords. He has won many prizes at the East Japan Traditional Crafts Exhibition, and his braided cords, which enhance the beauty of kimonos, have been well received and he has given many demonstrations at department stores and kimono stores.

Edo Braided Cords Supporting Japanese Clothing Culture

Matsudo City borders Tokyo and Saitama across the Edo River. The area around Matsudo Station, the center of the city, has a history of prosperity as a post station along the Mito Kaido Road in the Edo period (1603-1867). Despite its location amidst such scenery, Nakamura Masashi, a long-established Edo kumihimo (braided cord) shop in Matsudo that has continued to carry on the history of traditional crafts for about 130 years since the Meiji Era, is located in the area.

Edo Kumihimo passed down from generation to generation

Kumi-himo is a traditional craft with a history of about 1,400 years. As the name suggests, it is made by combining several strings of threads to create a strong cord that is easy to tie and hard to untie. It has been used for a variety of purposes, such as strings for scrolls with sutras written on them and strings for armor, but demand for obijime expanded especially in the middle of the Meiji period (1868-1912), when the o-taiko knotting style of tying obi (sash) became popular. Even today, “Edo Kumihimo,” which was refined in the old town people’s culture, continues to support the Japanese dress culture.

Nakamura Tadashi also mainly produces obijime and haori cords. Nakamura Tadashi says, “The method of making kumi-himo has been handed down from generation to generation through trial and error. So, in this braided cord business, I am faithful to what has been handed down, and I do it with precision,” says Nakamura. Without being eccentric, the braided cords are to stabilize the obi or haori and to enhance the overall appeal of the kimono. Nakamura’s braided cords are so highly regarded that he now receives requests for haori cords from professionals and comic storytellers.

Fresh colors in tradition

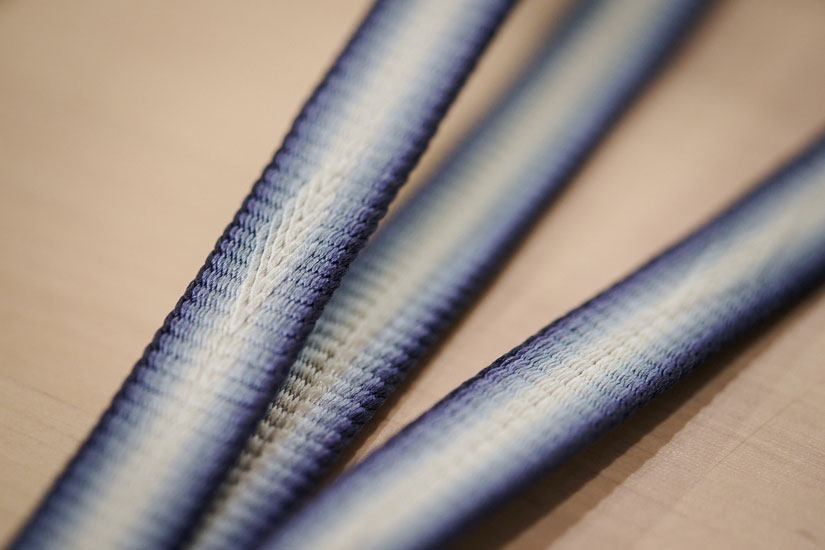

The raw materials for the braided cords made in Nakamura’s workshop are silk yarns, and most of the plain dyed cords are dyed by Nakamura himself.

Nakamura says, “I dye while envisioning the shape of the finished braid. He says, “The color must be one that can be used to coordinate with a kimono. I am always looking for colors that have been around for a long time, but also give a fresh impression. How can we interpret tradition in the modern age and brush it up? The dyeing process offers a glimpse of such a quiet challenge.

Unique techniques and tools for kumi-himo

Braided cords are made in various parts of Japan, and each region has its own characteristics. Kyoto’s kumi-himo has a flamboyant coloring, reflecting the noble culture of the nobility. Edo kumihimo, on the other hand, reflects samurai society and merchant culture, and is unique in its use of subdued colors and the braided patterns created by the crossing of threads and yarns.

There are four main types of stands for braiding: round, square, twill bamboo, and high.

Hand-kumihimo, a technique that requires a fine sense of balance

The most typical stand for Edo kumihimo is the round stand. The first step in the process is to make a bundle of threads and tie it to a “kumitama” (braided ball).

As the number of threads per bundle is reduced and the number of balls is increased to 8, 16, 24, and so on, it takes more time to complete the braid, but more detailed expression can be achieved. Nakamura calls this “the number of pixels in a braided cord” in a modern way.

The strings attached to the braided balls are placed on a round stand and braided while crossing diagonally opposite strings. The braided cords extend downward each time they are braided because the braided cords are suspended by weights from holes in the upper board of the round stand, and the weights are gradually applied to the cords. This is the reason why Mr. Nakamura calls “kumi-himo is mechanics.

Nakamura says that good braided cords are “moderately tight and flexible,” and that machine braided cords tend to be too tight and hard. The proportion of machine braided cords has increased considerably due to the balance between cost and productivity of obijime, and almost all cords distributed are machine braided. The percentage of hand-knitted strings is really decreasing. That is why the value is found in hand-knitted strings, which have both the skill of braiding and the ability to determine the weight of the weight to be used,” he says.

In addition, the degree of twisting to give strength to the strings also affects the hardness of the finished product, so the degree of twisting must be adjusted one by one with fingertips. The difficulty of braided cords lies in how to balance these various factors,” he says. But the abundance of variations is the fun part of making things.

Inheriting tools filled with the wisdom of predecessors

In addition to the round stand, Mr. Nakamura also makes active use of the “Ayatake stand. Ayatake stands are used for weaving by inserting a weft thread to a warp thread, just like in weaving. While the beauty of the braid is accentuated by the use of a round stand, the ayatake stand is not as thick because it is hammered in with a spatula, and is characterized by its neatness and fine texture.

Mr. Nakamura is also in the process of repairing an old kumidai he inherited from a retired craftsman. The wooden gears mesh with each other to form a semi-automatic string. Mr. Nakamura hopes to pass on the wisdom of his predecessors.

Mr. Nakamura’s Aim for Kumihimo

Mr. Nakamura began learning to make kumi-himo at the age of 17. After two years at a crafts school, he became involved in the family business in earnest, but at first he was so absorbed in the process that he was not interested in the colors and designs. However, after she began to sell kimono at department stores and kimono stores, Nakamura’s mindset changed.

Obijime that enhances the beauty of a kimono

I went from looking at braided cords at home to actually meeting people wearing kimonos at demonstrations,” he says. From there, I became more and more interested in coordinating kimonos, and I got into making obijime,” he says. Mr. Nakamura is now particularly interested in kumi-himo, a type of braided cord. In addition to the functional aspect of a firm tightening, it is “an obijime that looks beautiful when combined with an obi and a braided cord.

Nakamura’s approach to making obijime with the idea of coordinating with kimono and obi in mind is as follows: “Subtract patterns and colors rather than adding them. Even a single color can be seen as expressive enough,” and the goal is “the beauty of the overall appearance of the kimono rather than an over-emphasis on the obijime. By doing so, he says, “Obijime that can be easily matched with various kimonos are created.

Nakamura’s style incorporates a modern sensibility into this basic stance. Nowadays,” says Nakamura, “a slightly thinner obijime is more popular. It gives a cleaner appearance,” he says. Nakamura says that the observation he has gained through demonstrations enriches his own sensitivity.

Handing down the culture of kumi-himo to future generations

Nakamura confides that the number of craftsmen in the world of kumi-himo is decreasing. Even if the younger generation is interested in kumi-himo, it would be a waste if they are forced to say that it is impossible for them to work with it. At least, I would like to lay the groundwork so that they can manage to make a living. The reason why he has started participating in traditional craft exhibitions is not only to brush up his skills, but also to have people recognize the quality of his work and to link it to a reliable sales channel. In fact, until now, he has dealt almost exclusively with wholesalers, but the number of kimono stores and other interested parties has increased, leading to the diversification of sales channels.

Mr. Nakamura also focuses on training his assistants. I think the great value of traditional crafts is that they can be handed down to future generations and continue to be made, even after my death,” he says. Edo kumihimo is the product of Nakamura’s will. It is sure to continue to beautify people’s outfits in the future.