Ryukyu classical music, said to have been played at the royal court during the Ryukyu Kingdom era. This music has endured the hardships of the kingdom’s downfall and the Battle of Okinawa, and continues to thrive in the hearts of the people to this day. National Living Treasure Owan Kiyoyuki has dedicated his life to exploring the essence of Ryukyu classical music through both performance and theoretical research.

Ryukyu Kingdom-era court music and Ryukyu classical music

Okinawa was once the Ryukyu Kingdom. The music that developed as court music during that era is known as Ryukyu classical music.Ryukyu classical music is primarily composed of “uta sanshin,” which involves singing Ryukyu songs in an 8-8-8-6 rhythm while playing the three-stringed string instrument called the sanshin. Depending on the piece or stage setting, accompanying instruments such as the koto, kokyu, taiko drums, and flutes are added, creating an elegant world. Representative pieces range from 12 to 13 minutes, with some lasting over 20 minutes.

During the Ryukyu Kingdom era, classical music was performed exclusively by the samurai class as part of their official duties at the royal court. After the kingdom’s fall, the samurai who lost their official roles left the castles and began performing commercially for the common people. Since then, this art form has been passed down through generations, and Ryukyu classical music has been preserved in Okinawa across the ages.

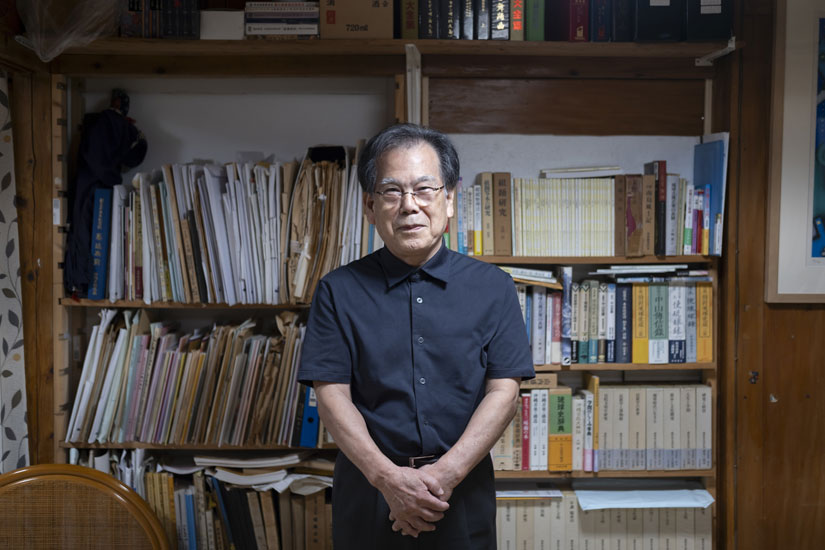

A master of Ryukyu classical music in the Afuso-ryu style, Owan Seiji is a renowned performer of the three-stringed instrument and flute, active on stages such as the National Theater of Okinawa. He is also known as a scholar dedicated to researching the theoretical framework of the “forms” within the Afuso-ryu style.In 2023, his contributions were recognized, and he was designated as a Living National Treasure and a holder of Important Intangible Cultural Property for Ryukyu Classical Music.

Self-taught master of the sanshin and flute

My parents are performers of Ryukyuan classical music, and I grew up listening to them play the sanshin. When I was in elementary school, I started teaching myself to play the sanshin that was at home, and I began singing and playing Okinawan folk songs that I had heard on the radio. I started developing an interest in classical music when I was in middle school.By listening to his father’s daily practice sessions at home, he naturally developed an ear for the music and eventually learned to play one of the masterpieces of Ryukyuan classical music, “Fishibushi.”

“My father didn’t know I could play, so he was surprised when I performed it for him for the first time. He said, ‘You’re really good!’ Then he invited me to join him, and I started participating in practice sessions with the adults.”

I also started playing the flute in middle school. The reason was a certain incident related to music class.

“In class, we needed a vertical flute called a recorder (at the time, they were mainly made of bamboo), but I accidentally bought a horizontal flute used in Ryukyuan classical music. I couldn’t bring myself to tell my parents, who had paid for it, and the music teacher didn’t tell me to replace it, so I ended up playing the horizontal flute alone in class.Unlike vertical flutes, which produce sound simply by blowing air directly into them, horizontal flutes require some experience to produce sound. Since the teacher had no experience with horizontal flutes, I had to learn everything on my own. Later, I started joining my father’s practice sessions on the flute. Thinking about how I might never have ended up playing the flute in Ryukyuan classical music if I hadn’t made that mistake, I realize how interesting life is.”

Ryukyu classical music schools: Nomura-ryu and Anfu-so-ryu

Ryukyu classical music has three major schools: Tansui-ryu, Anfu-so-ryu, and Nomura-ryu. Mr. Owan is currently renowned as a master of the Anfu-so-ryu school, but his father belonged to the Nomura-ryu school. He says that until he was in high school, he studied the three-stringed instrument and flute of the Nomura-ryu style under his father.The reason he joined the Anfuso-ryu was because he met Nishie Kishun after graduating from high school. Nishie was a performer who was designated as a Living National Treasure for “Kumi Odori Music Sanshin” in 2011. At the time, Nishie was studying under Miyazato Haruyuki of the Anfuso-ryu.

“One day, Nishie invited me to go with him to Miyazato-sensei’s place. At the time, there were few people who could play the flute in Ryukyuan classical music, so he probably took me along because I was one of the few who could play it.I played the flute in front of Miyazato-sensei, and Ohama Choei-sensei, a master of the flute, listened over the phone. This led me to join the Anfu-so school, where I studied the three-stringed shamisen under Miyazato-sensei and the flute under Ohama Choei-sensei.“

The melody of a song not written in the ”Koukou-shi” sheet music

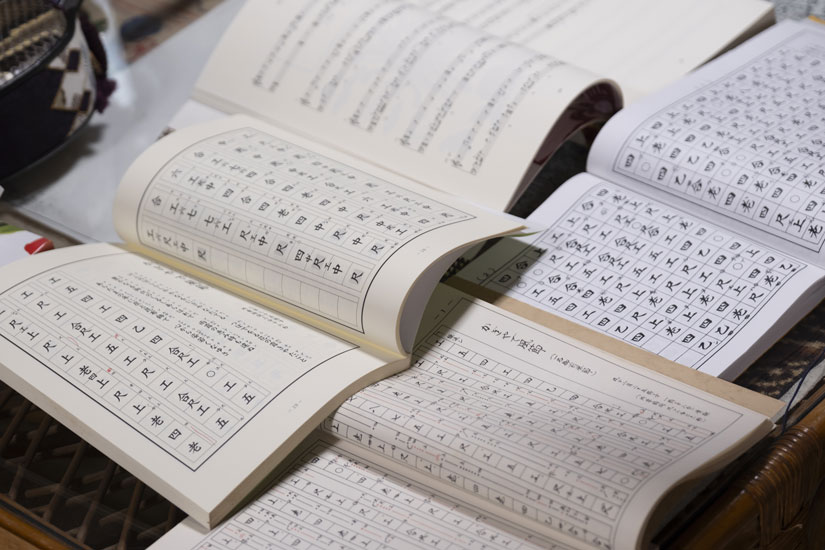

Okinawan music is typically performed by a single person who sings and plays the sanshin simultaneously, as the two are inseparable, hence the term “uta sanshin” (song and sanshin). The sheet music is called “kunkunshi,” which includes notations for the sanshin’s fingerings and vocal melodies.The major difference between the Nomura style and the Anfu-so style lies in the “kunkunshi.” While both styles include hand positions for the sanshin, the vocal notation is written in the Nomura style but not in the Anfu-so style. Therefore, while the Nomura style is sung according to the vocal notation, the Anfu-so style is transmitted orally from master to disciple, which is a significant characteristic of this style.

“At first, I was confused by the difference between the singing style I had learned from my father in the Nomura-ryu and the singing style I was learning from Mr. Miyazato in the Anfu-so-ryu. Furthermore, since there are no vocal scores in the Anfu-so-ryu, Mr. Miyazato’s singing seemed to vary each time, leaving me unsure of what the correct way to sing was. Moreover, even when studying under the same teacher, interpretations can vary from person to person, resulting in differences in singing style among disciples.Folk songs are a form of music where each person can express themselves freely, but classical music is a form of music with rules and formal beauty. Even though I was studying the same Anfuso-ryu style under the same teacher, I wondered if such discrepancies were acceptable. Even though I was singing in a way that my teacher had approved of, I was sometimes criticized by other students, and I struggled with where I should place myself.

Theoretical research that began with concerns about differences in performance

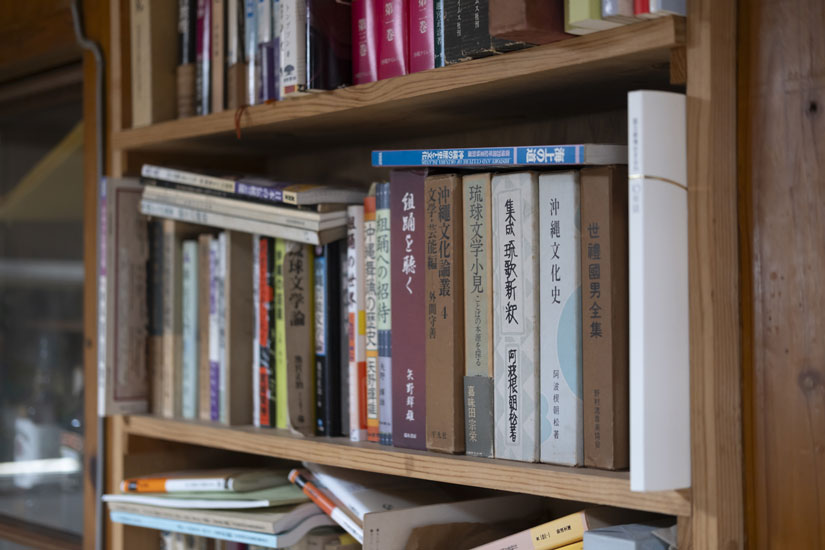

So, Mr. Owan decided to trace the origins of his master’s singing style and pursue a theory that he could fully accept, relying on the few remaining old documents on Ryukyuan classical music.Among the recordings of Anfu-ryu songs and sanshin performances, the oldest is said to be the performance by Kin Ryōjin, along with the paper “Ryūkyū Ongaku Kō” written by Tomihara Shusei. As his research continued, he discovered that the performance and theory corresponded, and he began to identify the “patterns” (forms) within them.

“In other words, I was able to clarify the rules behind why certain singing techniques are used. Classical music is composed of small parts, or patterns, that come together to form a single piece. By understanding the fundamental patterns, I no longer feel lost, and I can play with a sense of ease.”

At the same time, he came to believe that even in classical music with its rules, “differences in individual performers are acceptable.” “Mistakes and differences are two different things,” Owan explains.

“Mistakes are not allowed, but differences are acceptable. I want everyone to share this understanding. Simply imitating the master is not enough; you must play in your own way, using your own sensibilities, to create authentic music. It is important to have a sense of what is acceptable within the rules. For example, the pauses in singing. These can be described as changes in length or rhythm.The subtle timing is what makes it art. If you stick too much to the rules, it becomes bland. But you can’t just break the rules either. That subtle timing comes with repeated practice. So, I think it’s important for the individual to have some leeway in how they apply the rules. It’s important to have an environment where individuality is accepted. I want to create an environment where young people can express their individuality.”

The happiness of still having goals

Mr. Owan describes his own path as “still far from complete.” The lyrics of classical music from the Ryukyu Kingdom era tell the stories of the people who lived during that time. How should these lyrics be sung so that they resonate with people of a different era? Should the vocal techniques used when the music was performed acoustically within the palace be employed, or should the louder vocals used during the period when the music was performed outdoors be adopted? Alternatively, should the vocal techniques be adapted to suit the post-war era, when sound equipment became available?How can one pursue their best voice? Where does one draw the line in preserving Ryukyu classical music?

“Every day, I experiment and make mistakes, and because I feel it’s not yet complete, I want to keep going. Having goals to strive for is a source of happiness.”

Through doubt and pursuit, and repeated new discoveries, Owan’s journey to sincerely explore Ryukyu classical music will continue.