Located in the northeastern part of Fukui Prefecture, the “Kamishō Satoimo” from Ōno City is a brand-name vegetable known nationwide for its small size, tender texture, firm consistency that doesn’t fall apart when cooked, and chewy, mochi-like mouthfeel. It is a unique variety that cannot be grown in other areas. What kind of farmers’ dedication and passion go into producing this Kamishō Satoimo?

“Uesho Satoimo” cannot be grown anywhere else.

The cultivation area of “Kamishō Satoimo” is located in Ōno City, which borders Gifu Prefecture and is one of the heaviest snowfall areas in the Hokuriku region. Surrounded by mountains over 1,000 meters high, including the sacred Mount Haku, the area is a fan-shaped plain with well-drained sandy soil formed by sediment from the mountains. The significant temperature difference between autumn and winter is said to enhance the sweetness of crops, and many of the rice and vegetables grown here, nourished by the gentle mountain spring water, are specialty products or raw materials for Fukui Prefecture.

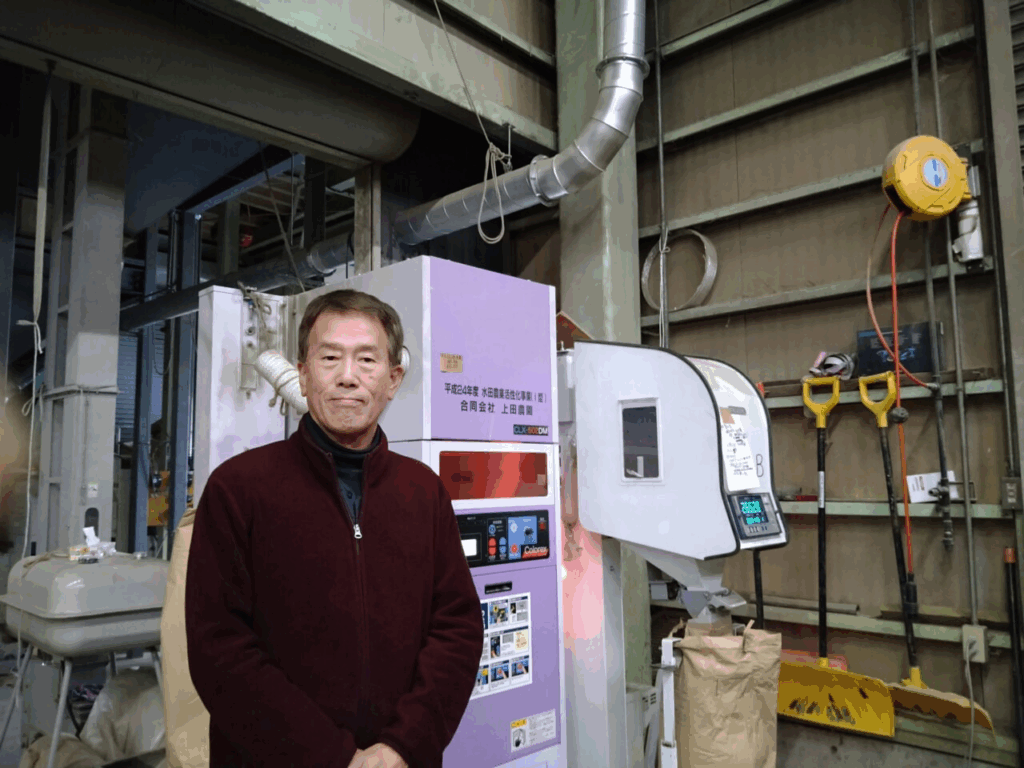

In the Kamijo district of Ono City, Kamijo Satoimo Co., Ltd., a joint venture company, cultivates and sells “Kamijo Satoimo.” Established in 2007 by Teruji Ueda, the current representative and a former full-time farmer, the company was founded to preserve agriculture in the region, where production has been declining due to an aging population. It was a pioneering effort to diversify agriculture, which had been passed down through generations, to support the local community. The company currently employs 10 people and operates approximately 120 hectares (equivalent to about 26 Tokyo Domes) of farmland, producing and shipping 27–28 tons of Kamijo Satoimo, as well as rice, soybeans, buckwheat, and wheat.

The characteristics of the land are reflected in the taste and texture of satoimo.

The wine term “terroir” refers to the soil, climate, and growing environment, but it also seems to apply to satoimo. The main production areas of satoimo in Fukui Prefecture are centered in the Okuechi region (the northeastern part of Fukui Prefecture, including the Ono Basin and surrounding areas). Depending on the region where they are grown, there are differences in size, stickiness, and taste. Even within Ono City, small areas like Kamishō, Shimoshō, and Sakaya have subtle differences in firmness and texture. During local festivals where people bring their satoimo to be cooked in large pots, “the firmness of Kamishō satoimo stands out, and when mixed with satoimo from other areas, they tend to fall apart, making the difference clear,” says Ueda with a smile.

Kamishō Satoimo was registered under the national “Geographical Indication (GI) Protection System” in 2017 to protect local specialty products unique to the region. However, there is no specific variety with that name; it is a traditional local variety that farmers in the Kamishō area have been cultivating for generations. About 50 years ago, Fukui Prefecture took the lead in selecting superior strains, maintaining and managing them as “Uejō Satoimo,” and promoting them as a branded vegetable both within and outside the prefecture. Because it is a variety deeply rooted in the region, even if you take the seed potatoes to another area and grow them there, they won’t taste the same. Due to its rarity, it commands high prices in the market during the peak shipping season.

It retains its shape even when simmered and has a moist, tender texture.

In the local area where the deliciousness of Kamijo Satoimo is well-known, the most common way to eat it is as “Ono’s local dish, Koroniku” (simmered dish). To fully enjoy the nutritious mucilage, the skin is not peeled off, but instead, the soil and outer skin are scrubbed off with a brush, and the potatoes are simmered slowly with sake, sugar, soy sauce, mirin, and a small amount of water until all the moisture evaporates. Finally, drizzle with mirin to give it a glossy finish. When you bite into it, the skin pops, and the strong sweetness and concentrated starch flavor blend with the chewy texture. It is also used in croquettes, oden, tempura, and noppei soup, making it one of the main dishes that brighten up the winter table in Ono.

Taking advantage of its characteristic inability to be grown consecutively, it supports the local agriculture.

At Ueda Farm, from late March to April, when the snow begins to melt, we cover the fields with plastic mulch to retain heat and plant the taro tubers. From May to June, we make holes in the mulch to allow the taro sprouts to emerge, then implement weed control measures.

Taro, native to Southeast Asia, thrives in steamy, humid climates and prefers heavy, sudden rains like monsoons, but good drainage is also crucial. By raising the ridges to prevent water from pooling in the soil and carefully managing irrigation while keeping the soil dry, the plants grow to over 1.5 meters in height by August. Harvesting begins in mid-October, with each plant yielding approximately 500 grams of Satoimo. Harvesting is completed before the first snowfall, and sorting and shipping are finished by late December.

During the peak shipping season, local staff are hired part-time to ensure sufficient manpower. The central figure is Terumi-san, the wife of the owner. Each tuber is carefully separated by hand from the dug-up plants, and quality checks are conducted to remove those with insufficient drying, damage, rot, or disease. “Large tubers are shipped as is, while smaller ones with difficult-to-peel skins are processed in a potato washer to remove the outer skin before shipping.”

The Mission of Full-Time Farmers in an Aging Society

Uesho satoimo (taro) has been a popular winter food due to its long shelf life and high nutritional value. However, once a field is used for satoimo, it must lie fallow for seven years to avoid crop failure caused by soil depletion.

Mr. Ueda took over farmland from neighboring farmers who found rice cultivation difficult and achieved efficient cultivation by rotating crops such as satoimo, rice, soybeans, and wheat. “As the aging population progresses nationwide, many rice fields are left abandoned. By taking over these fields and managing them efficiently, I hope to contribute to regional revitalization,” he says. Between crop rotations, the fields are flooded with water, which cleans the soil of impurities. Growing soybeans or wheat improves soil texture and drainage, so these crops are planted the year before the field is used for taro.

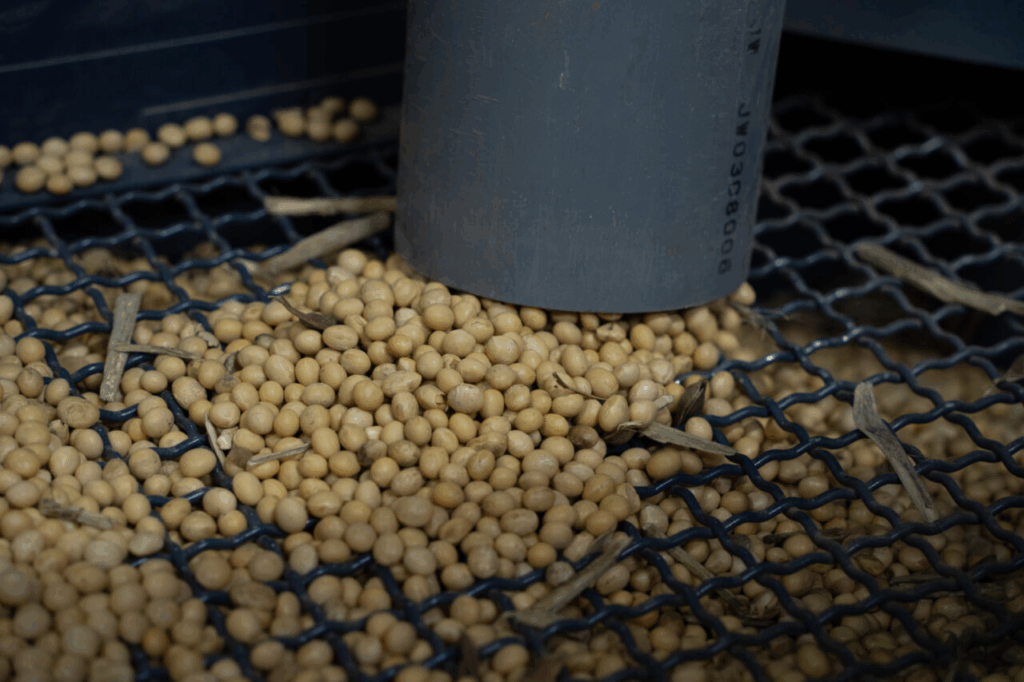

Ueda-san also cultivates another brand vegetable unique to the Kamijo region. It is a traditional local variety called “O-daruma Aodai,” which has been grown in this area for generations. The beans are large, smooth, and have a strong sweetness. The black spot on the belly makes them unsuitable for sale as miso or other products, so they have traditionally been consumed only within the community. “These are rare, traditional native varieties that local women have kept alive because they’re so delicious,” Ueda says proudly. They also make excellent boiled beans, miso, soy sauce, and tofu. This Oodaruma Aodai soybean can only be grown in Kamijo and requires a lot of effort, so it cannot be produced in large quantities. Ueda cultivates them using reduced pesticides and no chemical fertilizers, and processes them to enhance their brand value.

Embracing the 6th Industry for Regional Revitalization

“The joy of creating and the happiness of eating are our company’s motto,” says Ueda. To add further value to Uejō Satoimo, he established ‘Uejō Agricultural Processing Co., Ltd.’ in 2009 and began processing and selling rice, soybeans, and Satoimo. Uejima Satoimo, strictly managed as a branded vegetable, has strict shipping regulations, inevitably resulting in some damaged or imperfect produce. Ueda’s farm alone produces 600–700 kg annually. He collects this from the entire region, ensures a consistent supply, and sells it as processed products. They developed a “side dish series” of products like “frozen Uejō taro” and “premium taro croquettes,” which are easy to enjoy at home without preservatives or chemical seasonings. These are sold at roadside stations, wholesalers, and their own website.

They are expanding production in an environment where even elderly women can work comfortably.

Uejima Satoimo, a brand-name vegetable that has gained nationwide popularity, is facing a potential decline in production due to the aging of farmers, according to Ueda. For example, during harvest, satoimo grows by attaching baby tubers to the parent tuber planted in the ground. After digging them up, the tubers must be transported to the workspace in their original state, where the hard, inedible parent tubers are separated using simple specialized tools. The plants, still covered in soil, are heavy, and transporting them from the field to the truck, then from the truck to the workspace, as well as returning the soil to the field, is a time-consuming and labor-intensive process.

Ueda-san recognized this issue over a decade ago and has been working to mechanize the production and shipping of satoimo to reduce reliance on manual labor. He collaborated with manufacturers early on to mechanize processes from field preparation to planting and harvesting, and in 2020, he conducted pilot tests of a harvester that can pick up taro tubers without human intervention, wrap them in nets, and load them onto trucks, as well as a machine that separates parent and child tubers. Going forward, he plans to incorporate IT technologies such as GPS-based planting to further reduce farmers’ workload and expand production.

“Not just in Ono, but across the country, the number of producers is declining. We need to improve efficiency from planting to harvest, make production more accessible for women and the elderly, and ensure sufficient profits to sustain operations.”

As harvest volumes increase, sales channels become essential. Ueda is actively expanding sales through the company’s website and e-commerce platforms. He emphasizes that agriculture is not just about production but also generating revenue, and that contributing to regional revitalization is his mission.

Currently, Ueda Farm offers a two-day weekend, paid leave, and maternity leave to encourage long-term employment. As a result, the staff is primarily in their 30s and 40s. By working alongside this younger generation and sharing visions and aspirations for the future of agriculture and the region, Ueda believes that Ono’s agriculture will be preserved and nurtured alongside traditional varieties.