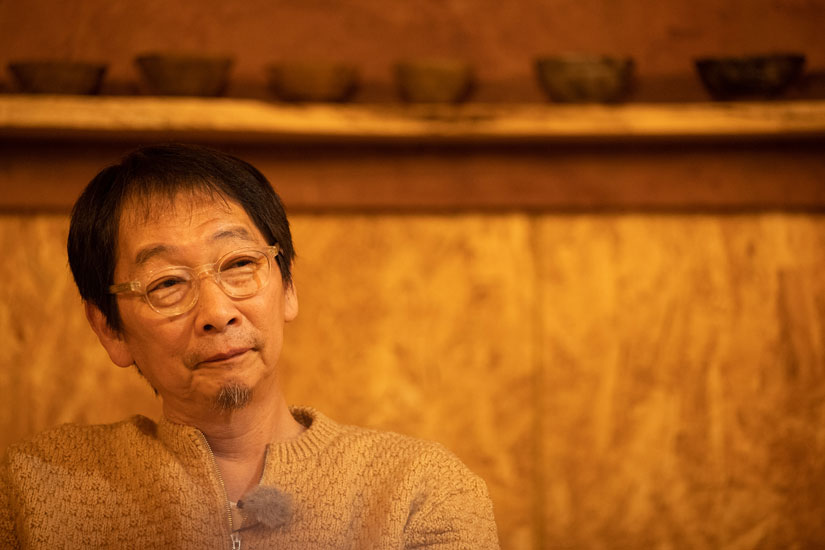

In Numata City, Gunma Prefecture, Yoshizawa Ryoichi is the third-generation owner of a 100-year-old finger joint shop. Finger jointing is a traditional Japanese technique of assembling furniture and fixtures without nails or metal fittings, using only wood. Yoshizawa combines this finger jointing with lacquer work to create “lacquerware,” challenging himself to create new products that value human connections.

A 100-year-old traditional woodworking shop takes on the challenge of creating new works.

Yoshizawa Ryoichi, a master woodworker, learned the craft from his father, who founded “Yoshizawa Shibori Shop” in Numata City, located in the northern part of Gunma Prefecture, approximately 100 years ago. While working under his father, the second-generation master, Yoshizawa sought to enhance the wood grain of his pieces by incorporating lacquer techniques. At the age of 18, he spent a year apprenticing at a lacquer shop in Tokyo’s Higashi-Mukojima district. At the time, he used the “fuki-urushi” technique, which involves applying raw lacquer to the wood and then wiping it off with cloth, a method commonly used in woodworking to beautifully highlight the grain of the wood. He applied lacquer to the woodworking pieces made by his father and himself.

In his early 40s, while working on a commission basis, fulfilling orders as requested, his father, the second-generation owner, passed away. As he was reflecting on his approach to his work and preparing to take over the family business as the third-generation owner, the Great East Japan Earthquake struck. This disaster made Yoshizawa realize the importance of human connections, prompting him to reflect on his relationships with past customers and begin asking himself how he wanted to approach his work and what kind of craftsmanship he aspired to create moving forward.

Unbound by the traditional framework of finger joint work, he embraced a more free-thinking approach.

“When my son was in his third year of high school, during a career counseling session, his teacher asked him, ‘What do you plan to do in the future?’ He replied, ‘I want to take over the family fingerboard shop.’ That one sentence made me think he was willing to work with me. It made me want to create various things together, enjoying the process, and leave something behind. It really moved me.”

For Yoshizawa, who was considering ways to rebuild relationships with customers, his son’s declaration to take over the family business inevitably changed his perspective on work.

With many of his regular customers growing older, he also felt anxious about whether his son could continue doing good work in the future. He wondered if it was better to continue making pieces for his regular customers in the same way he always had, or if he should use the remaining years of his craftsmanship to create pieces freely. After much consideration, Yoshizawa began searching for a way to build a future together with his son.

What he arrived at was a “process-oriented approach to craftsmanship” that values dialogue with those involved, exchanging ideas with customers, and creating works together.

Yoshizawa says that he feels the greatest joy when creating works freely, unbound by the traditional framework of finger joinery. His shift from a craftsman focused on preserving tradition to a creator who enjoys expression has become a new charm of Yoshizawa Finger Joinery, leading to the acquisition of new customers.

The power of lacquer, an adhesive used since the Jomon period—Made with Earth

Yoshizawa revisited lacquer as a medium to create works freely, unbound by the constraints of traditional woodworking techniques.

“Basically, I use lacquer on wood. Lacquer has the role of organically connecting various materials, and in the Jomon period, it was also used as an adhesive. Therefore, I freely attach various materials using lacquer.”

As the words suggest, he uses rice husks, stone powder, and even items like pottery and iron coated with lacquer. Around this time, he also began seriously experimenting with “colored lacquer,” which involves mixing pigments into lacquer to create various colors.

“Lacquerware crafts are often referred to as ‘lacquerware,’ but since ‘lacquerware’ refers to the work of lacquer artisans, I prefer to call my work ‘lacquer craft.’ I value both woodworking and lacquer work equally, so I refer to my work as ‘lacquer craft.’”

The intersection of woodworking and lacquer connects various regional elements into works of art, which in turn connect people to objects. These connections then link people to one another, creating a larger, more profound wave of connection.

Focusing on a select clientele to pursue the work I truly want to do.

Currently, Yoshizawa is very selective about who he works with. As a result, he is increasingly involved in collaborative projects with chefs and architects from Japan and abroad, where he makes proposals as a woodworker and works together with them to create something.

“Rather than being asked to make something specific, I’m getting more jobs where I’m asked to join a project and come up with something interesting (laughs).”

Yoshizawa’s approach to creating things involves having extensive conversations with clients to capture their desired image and then bringing it to life through creative ideas. By focusing on a specific target audience, he is able to connect with people he truly wants to work with, and his work is expanding beyond genres.

“I prefer jobs where people say, ‘That’s interesting! Who made that?’ rather than explaining techniques or skills. I’m really enjoying being able to do that kind of work right now.”

Creative challenges begin with encounters with people.

Yoshizawa’s encounter with a chef who inspired him to focus his work on specific targets was a pivotal moment in his career. It all began when Chef Kotaro Noda of “bistrot64,” a restaurant in Italy that has earned two Michelin stars, asked a friend to guide him around the Tone Numata area in search of ingredients.

Yoshizawa, who has always loved sake, food, and people, and had accumulated knowledge over the years, accompanied Chef Noda on a two-night, three-day tour of farms in the area, introducing him to the local produce. As expected, the tour was a great success, and eventually, the conversation led to the idea of Chef Noda hosting a one-day dining event at a ski resort in Minakami Town. At that dining event, Yoshizawa’s work was used as tableware and was highly praised by Chef Noda.

The conversation continued about creating something new together, and when Chef Noda became the executive chef at Ginza Shiseido’s “FARO,” he commissioned Yoshizawa to create lacquerware boxes for serving dishes. The creative world of a restaurant where Italian and Japanese cultures overlap, and where food, tableware, and space come together. Discussing how to design the tableware that would play a part in this world, and brainstorming ideas with Chef Noda, the time spent exploring a worldview that only the two of them could create was incredibly enjoyable.

Not overdoing it, not underdoing it.

Meeting Chef Noda inspired me to narrow my focus, which has led to opportunities to create dishes that enhance various types of cuisine. I now receive requests from chefs of different genres and also seek advice from them, expanding my repertoire of dishes I can create.

“Creating and using tableware is about not overshadowing the dish itself. Tableware always accompanies food, and to highlight the chef’s creativity, the tableware must not overpower the dish. Finding that balance is the most important and challenging aspect of my work.”

I don’t find much interest in pieces that overemphasize traditional craftsmanship, making the “traditional” aspect too prominent. On the other hand, if something is lacking, it leaves me with the regret of thinking, “I should have done this a little differently.” When I can strike that middle ground, it feels the most satisfying to me.

“Working with chefs from various genres, I realize that my clients are very creative. Whether they are Western or Japanese chefs, they understand their own style and are seeking new ways to express themselves in exciting ways.”

To narrow down the target audience while still meeting truly interesting people, he holds an exhibition called “Autumn in the Sake Brewery” once a year, gathering craftspeople from within and outside the prefecture in an old sake brewery. There, in addition to showcasing works, she invites chefs to prepare daily changing lunches and dinners, allowing participants to experience the interplay between food and tableware, thereby gaining a deeper understanding of their use and feel. Even chefs who have since earned Michelin stars continue to participate.

What she wants to do upon reaching her 60th birthday

During the winter, Minakami Town in Gunma Prefecture is known for its heavy snowfall. Within this town lies the Fujiwara district, where a traditional wooden tray called the “Fujiwara Bon” was once crafted. This tray features a wooden surface carved with radial patterns using a chisel. The craft began in the mid-Edo period as a way to utilize the abundant local timber and generate income during the winter months. Some of the pieces were even presented to the imperial family and are now coveted by antique enthusiasts.

However, a few years ago, the last artisan passed away, and the tradition came to an end. Yoshizawa-san, who had seen the Fujiwara Bons in his youth, initially found them unappealing and thought they were outdated crafts that had fallen out of favor. However, after turning 40, he began to see their beauty and launched a revival project as he approached his 60th birthday.

Additionally, Yoshizawa feels that people who engage in craftsmanship tend to value the first-person perspective. Therefore, he creates opportunities to think in the second and third persons, fostering a collective discussion about new challenges beyond the third-person perspective through interactions with others.

“I believe that without carefully observing old things and interpreting their beauty in your own way, you cannot create something new. There are many techniques from the past that are no longer practiced today but can serve as references.”

He incorporates old and traditional elements as one of his expressive methods, blending them with images derived from conversations with clients. His unique style, rooted in traditional techniques and modern sensibilities, harmoniously combines a sense of coolness that is both intuitive and timeless.

The presence of colleagues who help him expand his horizons.

Since starting to work with Chef Noda, Yoshizawa has had more opportunities to think and talk about “food and agriculture.” New encounters have led to interesting interactions with people and connections with many stimulating individuals. Through projects with these people, he feels that his world is expanding.

“As I get older, when I talk to younger people, I want to have conversations that expand their world as someone who is older. However, I feel a growing fear that the people who can broaden my world are gradually disappearing.”

He emphasizes that interacting with people who can make the unknown world interesting and broaden one’s perspective is absolutely essential for someone who creates things.

When traditional techniques and inspiration from peers come together within Yoshizawa, another fascinating work unlike anything seen before will undoubtedly emerge.