Pate de verre,” the world’s oldest glass-making technique, has its origins in ancient Mesopotamia. In Kyoto, there is a couple of craftsmen who have sublimated this technique into a one-of-a-kind art craft by adding the essence of Japanese craftsmanship to it. Their eldest son, glass artist Tomofumi Ishida, is the one who inherits and evolves this technique.

The birth of glass was about 3,500 years ago. What is the oldest glass technique “pate de verre”?

Pate de verre ” is a technique that originated approximately 3,500 years ago during the ancient Mesopotamian civilization. It is a type of casting glass in which clay or stone molds are filled with silica sand, crystal, or metallic ore powder for coloring, and the entire mold is then fired in a kiln.

Glassmaking using this technique is thought to have continued for about 1,500 years, but when the technique of blown glass was invented in the late 1st century B.C. during the Roman period, pate de verre, which was more labor-intensive than blown glass, declined. Since there were no written records of the technique, it came to be known as a ” phantom technique.

Artists attracted to this “phantom technique

Pate de verre once again attracted attention at the end of the 19th century. This was triggered by the Art Nouveau movement. During this period, many artists, including Amalric Walter and G. Algee Rousseau of France, produced works in pate de verre. However, none of them disclosed their techniques, and the method of making pate de verre was once again shrouded in mystery.

In 1932, the Iwaki Glass Works, Japan’s first private Western-style glass factory, began to reproduce the technique, and in 1975, art historian and glass craft specialist Tsuneo Yusui, who has studied the Mesopotamian pate de verre in the field of experimental archaeology, published his first book on the subject, “The Mesopotamian Pate de Verre. In 1975, Tsuneo Yusui, an art historian and specialist in glass art, reconstructed the Mesopotamian pate de verre production technique from the field of experimental archaeology, and began public education on the technique in1977. In this trend, there were artists who incorporated the pate de verre into their work. Tomofumi Ishida told us, “It was a little later that my parents, who were dyeing designers in Muromachi and Nishijin in Kyoto, came across pate de verre and began to study it.

Aiming to create glass crafts that incorporate Kyoto’s sense of beauty

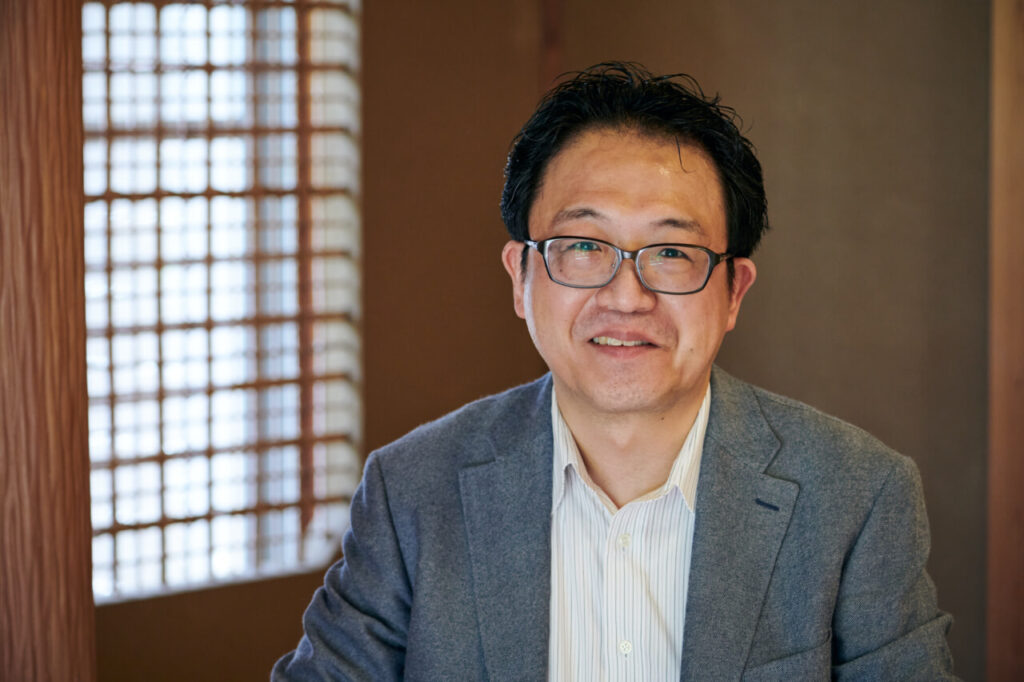

Wataru Ishida | Ishida Glass Studio (ishida-glass.com)

Tomofumi’s parents, Wataru and Seiki Ishida, who were active as kimono and obi designers, first heard of Pate de verre in 1985 when they visited an exhibition of Art Nouveau pieces. Wataru, who had always enjoyed ceramics, and Seiki, who had studied the tea ceremony and flower arrangement and loved beautiful things, were fascinated by the smooth texture of Amalric Walter’s nudes, which were different from glass or ceramics. The duo decided to create glass works with motifs of chrysanthemums, pine trees, pretty birds, and plants, while adding the essence of Japanese craftsmanship, which is their main occupation.

However, neither of them had any experience in making glass works. They even attended a culture class in town, but the finished pieces seemed completely different from the ones they had been attracted to. So, they purchased an electric furnace and began research at home while working as draughtsmen, but it was no easy task. The pate de verre technique was not easy to understand, and the fact that the two artists wanted to create their own style made the hurdles even higher.

There was no one to serve as a benchmark. Seven years of groping

Seiki recalls that when he first began his research, he was very troubled by the fact that there were no predecessors to serve as role models.

In the world of traditional art, there are always masters, such as living national treasures. Whether to aim for the style of such masters or to go in the opposite direction. When there is a person who can serve as a benchmark, one’s own path is set. There were people in Japan and abroad who created pate de verre, but these people were not the benchmark for the couple’s research.

For example, the delicate use of color, exquisiteness, and meticulous handiwork that is created down to the smallest detail. The couple, who both work in the traditional art world of Kyoto, insisted on a pate de verre that would be aesthetically pleasing only to Japanese craftspeople. They wanted to complete a ” Japanese pate de verre ” that did not yet exist in the world, but was it really feasible? For seven years, they groped in the dark, side by side with anxiety, but they did not stop their research while earning an income from their work as designers.

Using plaster molds to break out of their predicament

The problem of ” cracking ” was a particular concern during the production process. Another problem was the limited number of shapes that could be produced.

One day, however, they saw a plaster mold being used in the ” kanshitsu” technique of lacquer painting and tried using it instead of clay molds, which allowed them greater flexibility in their production. I saw that plaster molds were used in the “kanshitsu” technique, and I decided to use them instead of clay prototypes, which gave me more freedom in my production. The Ishida’s goal of creating a pate de verre filled with the essence of Japanese craftsmanship was quickly approached.

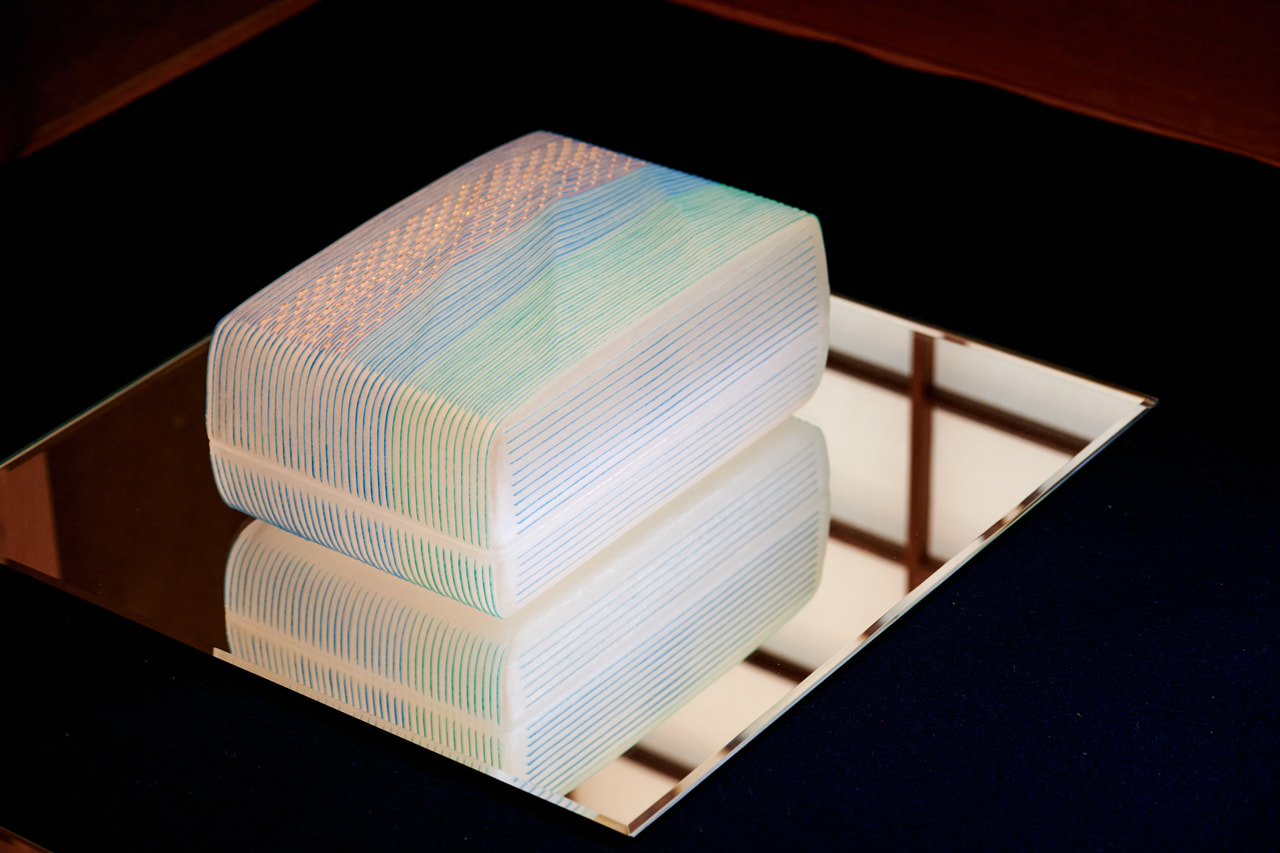

What the Ishidas created was a delicately crafted pate de verre in bright white. Until then, pate de verre was mainly dark-colored, heavy figurines and vessels typical of the Art Nouveau period, but works such as “Cleo de Merode” (owned by the Kitazawa Museum of Art) by Belgian-born glass artist Georges Deprez, which was well received in Paris from around 1900, are representative examples. Works such as “Cleo de Mérode” (owned by the Kitazawa Museum of Art) by Belgian-born glass artist Georges Deprez are representative examples. The fragile colors and textures of Mr. and Mrs. Ishida’s works, reminiscent of the amber sugar used in Japanese confectionery, and their appearance as if they themselves emit a faint glow, as well as the delicate patterns applied by the hand of kimono designers, have brought entirely new possibilities to the world of pate de verre.

In 2000, Wataru’s “White Pate de verre” won the Incentive Award of the Japan Crafts Association at the Japan Traditional Crafts Exhibition. In 2009, Wataru was recognized as a Kyoto Prefecture-designated holder of Intangible Cultural Assets, and the name ” cast glass” was given to his “Japanese part de verre. This was the moment when the research that the couple had begun together was engraved in history as a genre of traditional Japanese craftsmanship.

It took three months to complete the work. The work continues to require precision and concentration.

Pate de verre is completed through a number of processes. First, a prototype is made from plaster or clay, over which refractory plaster is applied to create the outer and inner molds. After carving a pattern on the outer mold and inserting colored glass powder into the carved grooves, the mold is filled with glass powder kneaded with glue and fired in an electric furnace. The firing temperature is about 800°C, which is lower than the firing temperature of blown glass, known as “hot work. The temperature is adjusted by opening the electric furnace when the firing temperature reaches 800 to 900°C so that the hot molten glass is spread to all areas between the outer and inner molds. On the other hand, if the firing temperature is too low, the glass will not melt, so delicate adjustments are necessary.

After three hours of firing, the plaster is allowed to cool slowly for three days to a week. The reason it takes this long is that refractory plaster and glass shrink at different rates. Rapid cooling deforms the plaster, and this distortion exerts force on the glass inside, resulting in the glass inside being distorted or broken. Therefore, it is necessary to cool it slowly. Although the process of slow cooling is now computer-controlled, this is still a very difficult point in the production of pate de verre.

The plaster mold is then broken, taking great care not to damage the glass inside, and the glass removed is polished and finished. It takes about three months to complete the entire process. The large number of steps and the time and effort required for each step are the characteristics of Pate de verre.

Tomofumi says, “It is necessary to imagine and calculate every detail of the finished product, including size and volume, to determine what kind of work you want it to be. This is because it is not possible to make modifications during the process. That is why he has to concentrate on each task, and the maximum working time is seven hours a day.

It was only after traveling around the world that I came to appreciate Japanese craftsmanship.

Born to Mr. and Mrs. Ishida, pioneers of Japanese pate de verre, Tomofumi studied at the Tokyo Glass Art Institute after graduating from high school, and then spent the next two years traveling around Asia, the Middle East, Latin America, and New York while devoting himself to art research. This period was also a time for him to explore his own position in the world.

After visiting various parts of the world and experiencing the objects made by different peoples, Chishi once again became aware of the beauty of Japanese crafts andthe magnitude of what his parents were doing. To this day, Tomofumi continues to add new essences to the genre of “Japanese pate de verre” that his parents established, aiming for further evolution.

Exotic,” “nature,” and “form. Evolving the inherited technique with his own themes.

While inheriting the delicate Japanese essence of Wataru’s and Seiki’s work, Tomofumi’s creations also have an oriental element in the use of colors, patterns, and forms. Chishi’s works are also inspired by nature, and his mastery of the different nuances of blue is also evident.

The “Pate de verre line engraved bowl ‘Kaze wo Kiku,'” which won the Asahi Shimbun Award at the 2003 Japan Traditional Crafts Exhibition, is one of the pieces that truly showcases his unique taste. This work was also highly praised for its success in producing a platter using an open piece mold, which requires more precise temperature control, rather than the press molds used by Wataru and Seiki.

My parents, who designed patterns for Nishijin textile belts and kimonos, focused mainly on patterns, but I have taken the opposite approach, thinking of patterns first of all in terms of form, ” says Tomofumi. By daring to explore his own style in an area that his parents have not yet tried, he is exploring the possibilities of Japanese pate de verre.

Japanese Pate de verre techniques that transcend oceans

In 2006, Tomofumi finally took up the challenge of making lids, which had been his parents’ forte, with his “Pate de verre Senkoku Mon Hako” (line engraving box), which won the Japan Crafts Association President’s Award attheJapanTraditional Crafts Exhibition. Chishi says that this piece best expresses the beauty of craftsmanship in which form and design come together, but at the same time, it is a piece in which he was able to realize his own unique style while following the style of his parents.

What can I do as an inheritor of the Japanese part de verre? The answer to this question, which Tomofumi has been searching for, seems to have come from “overseas.

In August 2022, Chishi was invited by the International Festival of Glass, a British glass organization, to give workshops and slide lectures at universities and other institutions to teach the technique of pate de verre.

The world’s oldest glass-making technique has been reconstructed as a Japanese craft genre after a long time, and has once again crossed the ocean to impress local people.

A couple who believed in the potential of Japanese crafts created the Japanese pate de verre. Tomofumi is now trying to convey this aesthetic to the world.