Ota Sake Brewery in Wakasakura-machi, Tottori Prefecture, brews sake in separate tanks for each producer and rice variety. Benten Musume is a sake that takes time to ferment well, and is perfect for warming up. We take a closer look at the roots of the sake brewing process by Shotaro Ota, the fifth generation of the Ota Sake Brewery.

A castle town with clean water where fireflies live

Located in the southeastern tip of Tottori Prefecture, Wakasa-cho (Wakasa Town) has a population of approximately 3,000 and is adjacent to Hyogo and Okayama Prefectures. The town is 95% forested and surrounded by three mountains, Hyonosen, Higashiyama, and Ouginoyama. Fireflies fly around the rich water source from the Hatto River that flows through the center of the town, and the starry sky is often seen. In the Kamakura period (1185-1333), “Wakasakura Onigajo” (castle of the Wakasakura demons) towered over the town, which was also a post town on the highway leading to Harima and Tajima Ryogoku (present Hyogo Prefecture).

There used to be several sake breweries, but now there is only one. Shotaro Ota, the fifth generation owner of the Ota Sake Brewery, has been working hard to produce delicious sake using local rice, even while the brewery has been closed for a period of time.

Brewing sake that continued despite being forced out of business

The history of Ota Sake Brewery dates back to 1909. The brewery became independent from the brewery where Mr. Ota’s great-grandfather, who was a toji (master brewer), worked. Every winter, the brewery invited the Izumo Toji from Shimane to brew sake, and the brewery has continued to operate in this style for generations.

However, when the toji became too old to come to the brewery, the company stopped making its own sake in 1992. Ota’s father, the fourth generation of the family to manage the brewery, relied on the practice of buying sake from other breweries by the bucket (i.e., buying sake made at other breweries and only storing and bottling it himself). After a 10-year absence from the brewery, Ota Brewery resumed sake brewing in 2002.

Shotaro went to college in Tokyo and worked at a local bank after graduation. After working for about seven years at outlets in Okayama, Osaka, and other prefectures, he decided to take over the brewery after seeing his father and the employees at the brewery resume sake production and become more energetic.

Benten Musume, a delicious local sake rice

Ota Sake Brewery’s only brand of sake is Benten Musume. The name comes from Wakazakura Benzaiten, which has been affectionately known as “Benten-san” since ancient times. The brewery named the sake after Benzaiten, the god of business, beauty, and water, in the hope that the sake would be as beautiful as Benten-san.

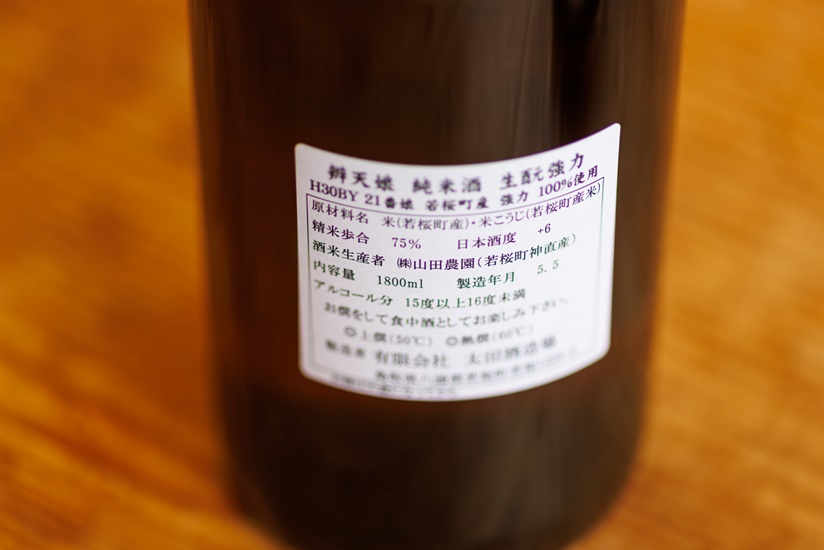

All sake rice is grown in Wakasakura-machi, and only contract and in-house grown rice is used. The main feature is that each farmer and each sake rice is brewed in separate tanks and shipped without any blending. The taste naturally differs with different producers. We want to express the unique flavor of each type of rice,” which is why the company decided not to blend the rice. The label not only lists the variety of rice, but also the name of the producer. Each brewing tank is named “No. 1 Musume, No. 2 Musume, etc.,” so that the customer can enjoy the differences in taste created by the brewing period, farmer, and sake rice.

Bringing out the best of Tottori’s indigenous rice

Five types of sake rice are used. They are “Goriki,” which is the revived rice of Tottori, “Torihime,” a new variety produced through crossbreeding in Tottori, “Tamasakae,” “Yamadanishiki,” and “Gohyakumangoku.

Among these varieties, Torihime is the shortest and most resistant to collapse, and its large grain size makes it easy to secure a good yield. The flavor is light, with a hint of apricot. However, it is difficult to handle because of its tendency to break easily during milling, so the number of breweries using it has dwindled to a few.

However, Mr. Ota has decided to take a hard look at the cultivation of Torihime, and has been cultivating it himself and discussing it with farmers who grow it under contract. He continues to observe the harvest, timing of fertilizer application, ear length, and other factors each year, and uses the data to share opinions on how best to produce the sake rice he wants.

Generally, when sake rice is polished, the more of the outer part of the rice that is shaved off, the better the flavor will be. This is because the outer part of the rice contains a lot of protein, and the more of it that is present, the more cloying the flavor will be. However, if rice can be produced with a lower protein content per grain, it can be made without a lot of polishing. Because he grows his own rice, Mr. Ota thought, “By adding rice without polishing as much as possible, we should be able to make sake that maximizes the characteristics of the rice.

Torihime’s Bentenmusume, made with such ingenuity, has a rich, apricot-skin-like aroma. This flavor was established because the rice was not cut down too much.

To achieve “even better when heated,” melt the rice thoroughly.

When Ota Sake Brewery reopened, they asked Mr. Hiroshi Uehara, an accomplished Tottori Prefecture sake brewing engineer, to provide guidance. Mr. Uehara’s philosophy of sake brewing: “Sake is pure rice, and it is even better when heated. He is a sake brewer who believes that sake is only good when it is heated up.

Just as freshly cooked warm rice tastes good, sake tastes better when it is warmed up, as the original flavor of the rice can be felt. In order for more people to drink sake, we want to make sake that does not sag easily even when stored at room temperature, and that can be drunk little by little every day.

To achieve this, we use only soft rice, which is possible only in Wakasakura-machi. When the temperature is high in the summer, rice becomes hard to protect itself, but in Wakakura-machi, where the rice is grown in cold water from the mountains, the rice is less likely to harden and grows softer. Softer rice melts more easily and slowly develops sweetness and flavor.

The brewery does not rely on the recommended timing of when the alcohol content reaches a certain level, but rather judges the timing based on whether or not the rice has fully dissolved. He believes that “good sake cannot be made without good rice,” and he places great importance on fully dissolving the rice so that the flavor of the rice will be reflected in the sake as much as possible.

It is said that if rice is fermented too long, it tends to develop astringency and bitterness, but letting the rice ferment for some time gives the sake a thicker flavor and a mellowness that comes from maturation. For this reason, it takes about two years for the sake to be ready for shipping, and some are aged for as long as 10 years.

If you know how to drink heated sake

Bentenmusume is only at its best when heated. Sake is best drunk at the same temperature as the body, as it is easily absorbed by the stomach, has a pleasant aroma, and goes well with meals. Bentenmusume also has a sourness that is due to the fact that it is fermented thoroughly, and it is said to stimulate the appetite as one drinks it.

In recent years, sake is often drunk chilled. But I want people to know that there is another way to drink sake: heated. I want to show people that there is an easy and delicious way to enjoy sake in everyday life,” says Ota.

We want to preserve it along with our food culture.

It is the sake’s food that you will want to match with the warmed sake. The culture of food and preservation is what allows sake to survive. That is why Mr. Ota has commercialized “nare-zushi” (fermented mackerel sushi) and “narazuke,” both of which have been eaten in Wakazakura since ancient times.

Wakazakura is a mountainous area surrounded by snow in winter. In the past, it was difficult to move around the town, and there were times when fish from the sea did not come in, which led to the development of nare-zushi, which can be preserved for long periods of time. The lactic acid bacteria produced from the mama (a type of rice wine) brings out the flavor of the fish and slows its decomposition, allowing it to be stored for up to two months. Narazuke, on the other hand, is made by slowly marinating the fish in sake-kasu (sake lees) for more than two years, and the seven times the fish is pickled gives it a mild flavor.

Although it is no longer made in every household, he hopes to preserve the unique taste of kamazuke and kasuzuke, as well as the sake that has been passed down with the food.

Sake that accompanies the daily life of Japanese people.

Bentenmusume may not be for the masses, as the longer it is aged, the more one can taste the differences in the flavor of each farmer’s sake rice. However, its unique flavor appeals to those who are attracted to it. And once you are hooked, you will be hooked.

While the consumption of sake is declining, Mr. Ota’s goal is to make sake that is close to the daily lives of Japanese people.

He wants to create sake that will be enjoyed for 100 years to come, and that will continue to be part of the food culture. Mr. Ota’s goal of sake brewing will continue in the future.