In a small town with a population of about 10,000 in Kamitakai County, Nagano Prefecture, there is a temple that is well worth a visit. It is Ganshoin, a Soto Zen temple located in Obuse Town, famous for its chestnut confections. This temple, where you can see masterpieces by the famous ukiyo-e artist Katsushika Hokusai, who was all the rage during the Edo period, attracts many tourists throughout the year.

Obuse Town is popular for sightseeing and confectioneries made with chestnuts.

Obuse Town, home to Gansho-in Temple, is located in the northern part of Nagano Prefecture, the same region as Hakuba Village, famous for skiing. Despite being the smallest municipality in the prefecture in terms of area, it preserves a rich history and traditional culture. The town is known for its picturesque streets and popular confectionery shops that specialize in chestnut-based sweets, making it one of the top tourist destinations in the prefecture. Gansho-in Temple is one of Obuse Town’s tourist attractions, attracting a steady stream of sightseeing buses during the season.

The stage where Kobayashi Issa recited a poem about himself, “Gansho-in”

“Skinny frog, don’t give up, Issa, here I am.” This is a poem by Kobayashi Issa, a poet from Shinano Province (now Nagano Prefecture) who, along with Matsuo Basho and Yosa Buson, is considered one of the leading haiku poets of the Edo period. It describes a small, thin frog fighting with a larger frog over a female frog. It is said that Ichiyō composed this haiku to encourage himself, drawing parallels between his own circumstances and those of the frogs. The pond where this scene took place is located at Gansho-in Temple.

The History of Gansho-in Temple

Founded in 1472, this temple has undergone many changes, including two fires, before reaching its current form. It is also famous as the family temple of Fukushima Masanori, a warlord known as one of the “Seven Spears of Shizugatake” and a close confidant of Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

Originally a vassal of the Toyotomi clan, Fukushima Masanori switched allegiance to the Tokugawa clan. In 1619, he was accused of violating the military regulations and had his lands in Hiroshima, which he was then governing, confiscated. He was exiled to the Shinetsu region, a punishment similar to demotion. At that time, Fukushima Masateru, who was a devout follower of Zen Buddhism, is said to have designated the temple as his family temple in his new domain.

The main attraction for tourists is Katsushika Hokusai’s masterpiece.

The main attraction for tourists visiting here is the “Hachiman Phoenix Painting” depicted on the ceiling of Oma. This is the work of Katsushika Hokusai, a ukiyo-e artist who left behind many masterpieces such as “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji.” Hokusai created this work during his later years while staying in Obuse Town. At the age of 88, Hokusai, with the full support of Takai Kōzan, a wealthy merchant from Obuse whom he had known in Edo, enlisted the help of his daughter, Katsushika Ōi, a ukiyo-e artist, and other craftsmen to complete this painting over the course of about a year.

The enormous phoenix painting covering the entire ceiling is said to be the largest of Hokusai’s works. Its powerful brushwork, which seems to leap off the canvas, and its vivid colors, which remain as vibrant as ever despite never having been repainted, captivate viewers. However, when it comes to sacred beasts painted on temple ceilings, the image of a dragon is probably more familiar nationwide.

So why a phoenix at Gansho-in Temple?

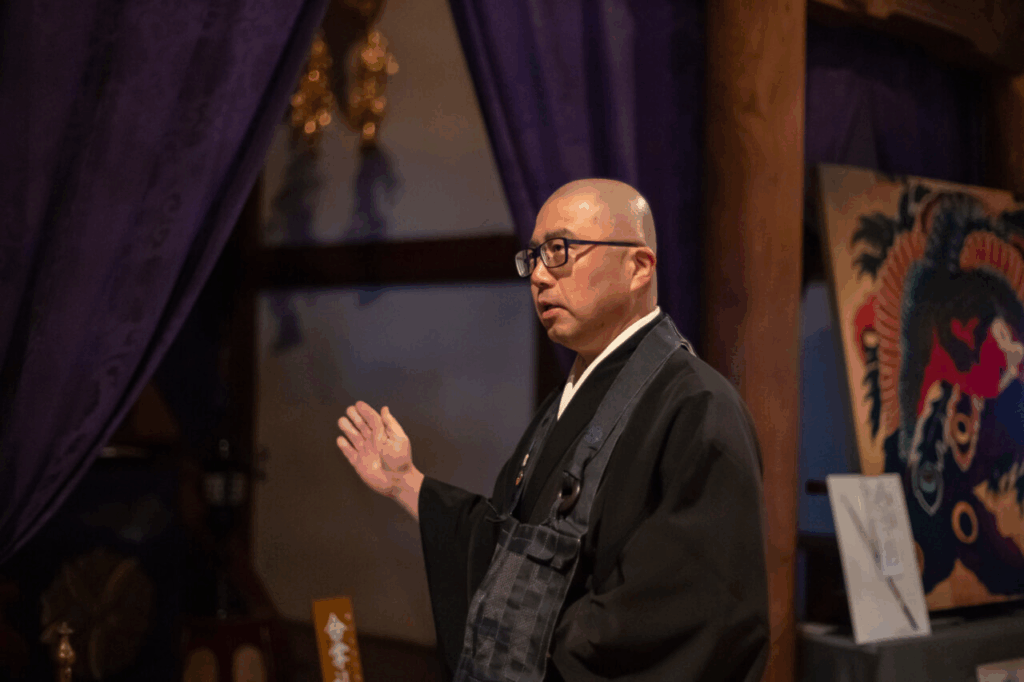

The head priest of Gansho-in Temple, Watanabe Masami, explains his interpretation of the “Eight-Direction Gazing Phoenix Painting.”

According to the head priest, Watanabe Masami, while there are no records in literature, he suggests that the inspiration for this work may lie in the thoughts of Takai Kōzan, who encouraged Hokusai to create it and was the project’s greatest collaborator. Takai Kōzan strongly felt the Buddhist concept of “impermanence” (mujō), which means “nothing in the world is permanent; everything is constantly changing,” in the world at that time. Hokusai, who understood this, may have depicted the “phoenix,” which represents the opposite of “impermanence,” or “eternity.” While this is merely Watanabe’s speculation, if it were true, it would be a touching story of the strong trust built between Hokusai and Takai Kōzan, who were nearly a generation apart, and the dramatic legacy they left behind in Nagano Prefecture with this masterpiece of the century.

Head priest Masami Watanabe and Gansho-in Temple

This year marks Mr. Watanabe’s eighth year as head priest. Before becoming a priest, he worked as a salaryman for 14 years. He graduated from the economics department of university, but did not major in Buddhism. However, his mother’s family home was Gansho-in Temple, so he had been familiar with Zen since childhood and was interested in it.

His interest deepened during his backpacking travels as a salaryman. Visiting Christian and Islamic regions, he encountered various religions, which prompted him to reflect anew on Buddhism and his own roots in Zen. Now, as the head priest of Gansho-in Temple, he draws on his experiences as a salaryman before entering the Buddhist order, as well as his diverse experiences as a traveler, to deliver sermons that follow the centuries-old Zen tradition while adding his own interpretations.