Located in Soma City, Fukushima Prefecture, a prosperous castle town, is Yamagataya Shoten, a small soy sauce and miso brewery that has been in business for about 150 years. Founded in 1863, the company has been in business under the name “Yamabun. The fifth-generation owner, Kazuo Watanabe, is the man behind this long-established business, which has been loved under the name “Yamabun. In the six years since he became the owner, he has won the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries Award, the highest award at the National Soy Sauce Competition, which has been held since 1973, four times. The name is spreading throughout the country.

Nationally Recognized Soy Sauce from the Fukushima Method

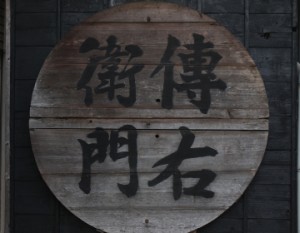

The wooden house has a time-honored charm. The storefront boasts an array of products, including shoyu, miso, koji (malted rice), amazake (sweet sake), and sagohachi (koji pickles). Hidetoshi Nakata turned his gaze toward the back of the store, following the aroma of the miso.

You also sell miso by weight,” Nakata said.

Kazuo Watanabe, the owner of the store, nodded smilingly and offered him a sample. We start with a taste of their signature product, Yamabun Honjozo Tokusen Soy Sauce. The deep, mellow umami and appetizingly savory flavor spreads in the mouth.

The process of making shoyu begins with the preparation of koji (malted rice) from soybeans and wheat. The malted rice is then used to brew the moromi, which is aged for six months and pressed to make kiage, or raw soy sauce, a labor-intensive and costly process.

In an effort to ease the burden on breweries, Fukushima Prefecture has decided to establish an integrated production system at its kiage factory. The Fukushima method of centralizing the production of namaage, pioneered in Japan, has spread to other parts of the country. Today, half of all shoyu sold on the market is made using this method.

There are various types of namaage, such as round soybeans and dark soybeans, and Fukushima Prefecture offers several types of namaage for each type. By combining them, it is possible to create a brewery’s own unique flavor.

Polished secret techniques enhance the flavor.

After the soy sauce is cooked, each brewery performs a fire-working process, which is said to be the most important step in bringing out the best of the shoyu. Mr. Watanabe takes us on a tour of the factory, explaining the ingenuity of each brewery.

The secret of adding “kaeshi” has been passed down from generation to generation at Yamagataya. The mirin (sweet sake) is boiled down, sugar and shoyu are added, and the mixture is left to simmer for 10 days before adding the kaeshi, which is added just before the temperature reaches 80°C. “Some of the brewers I know also use kaeshi,” says Watanabe. This is a unique technique that even the brewers I know have never heard of, but it adds depth of flavor and aroma to the finished product,” he says.

The process of heating the soy sauce over a period of time and then raising the temperature allows the higa, or aromatic flavor, to become more pronounced and to persist.

What kind of dishes does this shoyu go well with?

Mr. Watanabe thinks for a moment before answering, “Since it’s a shoyu from the sea, it goes well with fish,” he says. He recommends it for boiled fish such as flounder.

The color, shine, and taste are so good, and it doesn’t fall apart easily, that some professionals, including inns and Japanese restaurants, say they can’t use any other soy sauce,” he says.

In recent years, orders from all over Japan have been increasing due to the good results of the product at the competition. Mr. Watanabe’s smile is as happy as ever that the local people are so pleased with his product.

In the old days, every castle town had a brewery. In the old days, every castle town had its own brewery, and Soma used to be lined with many of them, but now it is the only one. I would like to pass on the castle town of Soma to the next generation through the taste of my hometown and its food culture of shoyu and miso.