Gunma Prefecture, home to the World Heritage-listed Tomioka Silk Mill, has long been a center of the silk industry. One woman is fascinated by the history of the silk industry and the process of producing thread from cocoons. She is Hiroko Nakano, a Zaryo dyeing and weaving artist. Ms. Nakano has inherited the “Jyoshu Zaguri,” a thread-making technique that had nearly died out, and has been presenting works that meet the needs of the modern age while preserving the traditional technique.

Inheriting the traditional Gunma Prefecture “Jyoshu Zaguri” silk spinning technique

Sericulture has long flourished in Gunma Prefecture. In 1872, the Tomioka Silk Mill was established as a model factory for mechanical spinning, contributing greatly to the development of the Japanese silk industry. The “Jyoshu Zaruri” developed in Gunma Prefecture at the end of the Edo period (1603-1867) is a method of spinning cocoons using wooden tools to draw threads from cocoons.

A device called a kosha is used to wind the cocoon silk from cocoons boiled in hot water to the desired thickness while turning the handle of the zaruri.

In order to inherit the now rare traditional technique of “Jyoshu Zaruri,” Mr. Nakano first studied spinning techniques at Usui Silk Mills, one of the largest silk mills in Japan, which produces 60% of Japan’s silk yarn, before opening the Zaruri dyeing and weaving studio “canoan” in 2003.

Zaruri” culture takes root in Gunma

One of the reasons why Nakano, who was born and raised in Takasaki City, Gunma Prefecture, was attracted to zaruri in Jyoshu is the historical background of this region, where from the end of the Edo period until around 1965, women in each household made thread from cocoons and made clothing for their families as a handicraft for sericulture farmers in Gunma Prefecture.

In order to protect the quality of the silk, cocoons that were no longer suitable for the factory and could no longer be shipped to the factory were used for zaruri in Jyoshu, which was practiced by the women of the farming households. While the Tomioka Silk Mill and other mechanized mills have been mass-producing yarn since the Meiji Era (1868-1912), the farmers did not want to see the “loving family business,” which had been passed down in the local community, die out.

Another reason he was attracted to Jyoshu zaruri was the overwhelming difference in feel.

He said, “There is something special about the fluffy, smooth, airy, and uniquely supple texture of textiles made from threads drawn by hand while slowly turning them with a wooden tool.

The charm of spinning raw silk from cocoons by hand

Nakano’s workshop produces a wide variety of cocoons, from ultra-fine yarns to extra-thick yarns suitable for thicker fabrics such as tapestries, and by taking advantage of the characteristics of cocoons, she produces threads of various cilia (ratio of length to weight, which indicates the thickness of a fiber or thread) and textures.

In the usual process of making yarns, thin yarns are first made and then twisted together to the desired thickness, but Nakano decides on the thickness of the yarn from the beginning and adjusts it directly from the cocoon to suit the purpose while feeling the thickness of the yarn with his fingertips.

Kimonos, obis, scarves, and other fabrics all require a certain thickness of fabric. The process of winding threads directly from cocoons according to the thickness of the fabric, with an image of the product to be made in mind, is truly a craftsman’s art.

Creating richly textured products by hand

Generally, the process of making cloth is a division of labor. Silkworm farmers raise silkworms and ship cocoons, which are then made into yarn at a silk mill. The dyeing shop dyes the finished threads, and the weaving factory weaves the dyed threads into cloth. The general public rarely learns about the process of how cloth is made.

Mr. Nakano, who has always loved cloth, became interested in how cloth is made, and in the process of researching, he came across Jyoshu Zaruri. He was fascinated by the process of making thread from cocoons and textiles from the thread.

Designing the threads and weaving the cloth by himself

With a desire to produce silk fabrics designed from threads, he began to learn various techniques of thread-making, including Jyoshu Zaruri, which utilizes the characteristics of cocoons to produce various textures. I also became interested in dyeing threads, so I studied natural plant dyeing. After producing beautifully colored threads, I wanted to try my hand at making cloth, so I learned to operate a high loom, a type of handloom used for silk weaving, and began to weave cloth. I learned to dye cloth and weave by hand on a loom through trial and error, although I sometimes learned from local dyeing and weaving experts.

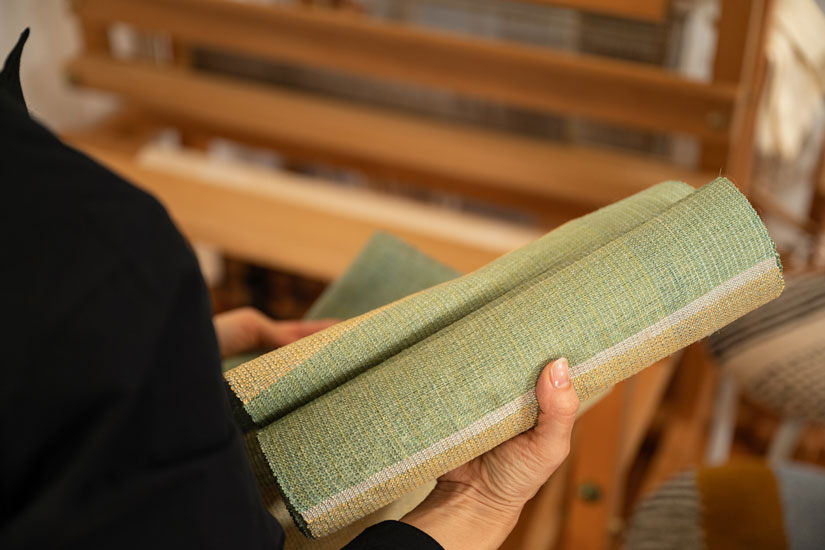

Having mastered the techniques of thread-making, dyeing, and hand-weaving one after another, Nakano began making kimonos, obis, and scarves that emphasize the texture and quality of the threads, which could not be achieved through the division of labor.

He dyes threads ground from cocoons with herb dyes and weaves them by hand into fabrics. I am fascinated by the depth and mystery of the consistent cloth-making process, which is done by hand as much as possible, using only natural materials.”

Dyeing with plants and trees, focusing on natural products

Nakano says that the charm of herb-dyeing lies in the fact that any combination of colors obtained from nature can be harmonized in a mysterious way.

He says, “I sometimes go to the mountains myself to gather materials for dyeing. I have more opportunities to get in touch with nature, and even with the same dye, the finished color differs depending on the environment in which it was grown, the season when it is dyed, the quality of the water when it is boiled, and other factors.

The Jyoshu Zaryo yarn, which has excellent dyeability, is dyed in natural colors by herb-dyeing, using only natural plants. When these yarns are woven on a high loom, they have a rich and deep expression depending on the fineness and color of the dyeing process, resulting in a beautiful silk fabric that is both fluffy and smooth, a quality that can only be achieved by handwork.

Preserving traditional techniques while making products that can be used in modern life

The silk industry that Mr. Nakano is engaged in is generally regarded as a niche industry that does not attract much attention.

Until now, the value of machine-made threads was that they were more neat and beautiful, but recently, more and more people understand the quality of handwork and the desire to preserve traditional techniques, and we are doing business with people with whom we have such relationships,” he says.

Because he adjusts the thickness of the thread as he designs, he often receives custom-made orders, but he also sells his own creations at exhibitions and private shows. Mr. Nakano believes that having more people use his zarrow thread creations will help pass on the traditional technique and convey the importance of the cultural background.

Aiming to create a traditional culture that can be worn easily

Mr. Nakano, who handles everything from yarn making to dyeing and weaving by himself, uses traditional methods to perform all processes by hand, which naturally limits the number of pieces he can make.

He says, “I want many people to use my products, but because they are not mass-producible, it is difficult for me to reach my customers.

Because they cannot be mass-produced, we aim to create products that will be used for many years to come.

Kimonos are characterized by their unprecedented lightness, and obis are highly regarded for their elasticity and ease of fastening. Scarves are also light and warm, and have a comfort that is different from machine-made products.

Although only a small number of scarves are made, the longer they are used, the more they become more comfortable to wear, as evidenced by the large number of repeat orders from people who have used them once.

Passing on skills and the possibilities of traditional crafts

Nakano has been an inheritor of Gunma Prefecture’s traditional crafts for more than 20 years, opening the Zaruri Dyeing and Weaving Studio and launching his own brand to preserve and disseminate the techniques and culture of Zaruri yarn-making in Jyoshu.

In order to promote awareness of traditional techniques and culture, I not only exhibit and sell my work at gallery exhibitions, but also demonstrate the Jyoshu Zaruri technique.”

In the future, he hopes to create a place where the process from thread to fabric can be conveyed in a more realistic manner. He said emphatically that he would like to expand awareness of traditional techniques and convey the charm of Jyoshu Zaruri to more people by having people who come into contact with silk fabrics there learn about and experience the world of sericulture and silk industry, which they had not known before.