In the southern part of Fukuoka Prefecture, in the satoyama of Tanushimaru-cho, Kurume City, there is Aiseian, a Kurume-gasuri weaving company that has been in business for seven generations. Kurume kasuri is one of the three major kasuri fabrics in Japan. More than 200 years after its birth, Kurume kasuri still attracts people with its simple texture of cotton, elaborate kasuri patterns, and beautiful indigo color that can only be achieved by indigo dyeing.

Kurume Kasuri, Born of a Young Girl’s Curiosity

Kurume City is located in the Chikugo region of southern Fukuoka Prefecture. In the late Edo period (around 1800), Kurume-gasuri was invented by a girl named Inoue Den, who was born under the castle of the Kurume Domain.

Inoue Den was intrigued by the spotted pattern on faded old clothes and unraveled the cloth to find out how it worked. He found white spots on the threads themselves, and using this as a clue, he tied white threads together, dyed them with indigo, and wove them, resulting in the appearance of a white pattern in the cloth. This was the beginning of the history of Kurume kasuri, a craft born of one girl’s curiosity and inspiration.

Since then, Den has continued to teach this technique to many people throughout her life and has worked hard to popularize Kurume kasuri. Kurume-gasuri became popular as a side job for farmers during the off-season, and from the Meiji period onward, it became popular throughout the country as clothing for the common people. In the early Meiji period, when production began to flourish, “Aiseian” also began its history as a weaving company.

Integrated production of about 36 processes

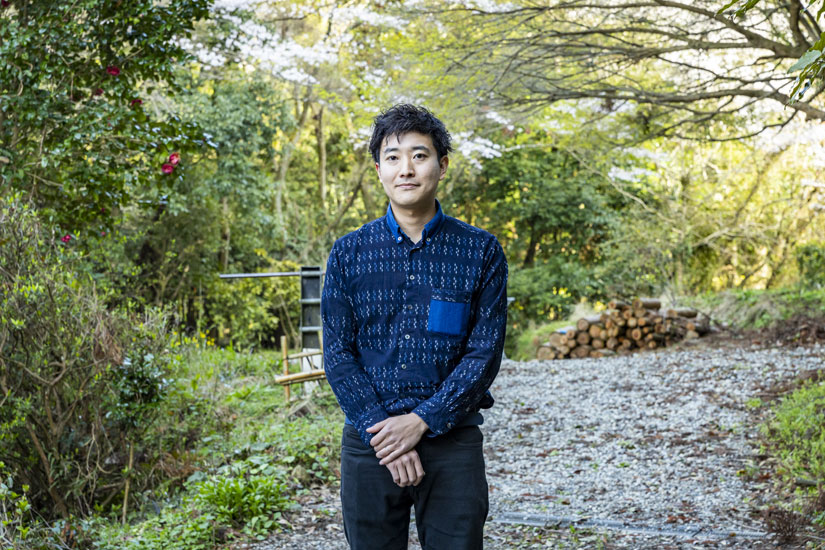

Aiseian’s current workshop is located in Tanushimaru-cho, Kurume City, at the foot of the Mino Mountain range. 30 years ago, the workshop was relocated to its current location in search of water, which is important for indigo dyeing. Takahiro Matsueda, the seventh generation, and his mother Sayoko, the sixth generation, produce Kurume-gasuri in the workshop surrounded by rich nature.

Kurume kasuri was the first cotton fabric to be designated an Important Intangible Cultural Property of Japan in 1957. The three requirements for certification are: “use of hand-knotted kasuri yarn,” “dyeing with genuine natural indigo,” and “weaving on a handloom. The process involves 36 steps, including designing (pattern design), weaving (dye-proofing), indigo dyeing, washing, hand weaving, drying (……), and so on. In its heyday, the division of labor was well advanced, but as times and demand changed, the number of weavers decreased. Today, there are only about 20 weavers left, and most of them are engaged in integrated production.

Ai fabric is made the old-fashioned way, using only the finest raw materials.

Among the many processes, one of the most distinctive of “Aiseian” is the indigo building process. Ai-kenchiku is the process of fermenting natural indigo in a jar to produce the indigo solution used to dye the yarns. The quality of the water is said to affect the quality of the dyeing process, and each weaver has its own method.

We do not use chemical dyes or chemicals, but use a technique that has been handed down since the Muromachi period (1333-1573). Natural indigo produced in Tokushima Prefecture, maltose and pure rice wine are added to the indigo jar, and fermentation is promoted by the action of microorganisms. My father loved to drink, but the indigo jar also loves to drink (laughs),” smiles Takahiro.

Takahiro first came into contact with Kurume kasuri when he was seven years old. His father, Tetsuya, would playfully let Takahiro help him dye the threads. In addition to the dyeing process, Takahiro also tried his hand at weaving by sitting on his mother Sayoko’s lap and learning as he went along. The workshop was close to where he lived, and the smell of indigo and the sound of weaving embraced him during his childhood. It did not take long for Takahiro to decide to pursue this career.

What is the unique way of expression at Aiseian?

Kurume kasuri is characterized by the various patterns expressed by the warp and weft threads. Because the threads are dyed before weaving, the outlines of the patterns become slightly out of alignment and blurred, which is what gives the kasuri its unique texture. In 1839 (Tempo 10), dyeing and weaving artist Taizo Otsuka invented the traditional pictorial kasuri technique using a picture stand, a technique that has survived to this day. This was an opportunity that greatly expanded the expressive possibilities of kasuri.

Even within the Kurume kasuri, there are regional differences in the kasuri pattern. In the Chikugo region, which is dotted with Kurume kasuri weavers, small patterns are specialized in Hirokawa Town and Yame City. In the area of Sanma-gun, where the head family of Aiseian is located, they produce large patterns, medium patterns, and even pictured kasuri.

The pictured kasuri technique is said to have been pioneered by Takahiro’s great-grandfather, Matsueda Tamaki, the third generation of the Aiseian family and a living national treasure. His outstanding technique and deep knowledge of waka poetry led him to create unique patterns, further expanding the range of expression of Kurume kasuri. His large, poetic, pictorial patterns inspired by the nature of Chikugo and the beautiful gradations of indigo color. This creativity has been passed down through the generations to Takahiro’s father, Tetsuya, who is certified as an Important Intangible Cultural Property Kurume-gasuri Technician, his mother Sayoko, and the current owner, Takahiro, and has shaped the current “Aiseian” style.

Chasing the Light Left Behind by My Father

After graduating from university, Takahiro left his hometown and worked for a company, but in 2020, when his father Tetsuya became ill, he decided to follow the path of Kurume-gasuri. For Takahiro, the Kurume Kasuri workshop is a part of his life and a place that holds fond memories of his parents. He had no hesitation in returning to his parents’ home. At the time, however, Tetsuya was a nationally renowned artist who had won numerous titles at prestigious exhibitions in the craft world, including the Japan Traditional Crafts Dyeing and Weaving Exhibition and the Japan Traditional Crafts Exhibition. Tetsuya was somewhat apprehensive about following in his father’s footsteps.

I am familiar with Kurume kasuri,” he said. Even after I returned to Kurume as his successor, even though I was anxious, I did not feel any gap or discomfort. My father never showed any pain in his face until he passed away, and he passed on his skills and heart to my mother and me to the best of his ability. It was a really good father-son time,” Takahiro recalls.

Tetsuya passed away shortly after Takahiro returned to his parents’ home, but coincidentally, Tetsuya’s posthumous work, Kurume-gasuri kimono “Hikaraku” won the Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Award at the 67th Japan Traditional Crafts Exhibition (FY 2020), the largest publicly-collected exhibition of its kind in Japan. This achievement was a ray of hope for the two surviving members of the family.

The two men took each other’s hands and wiped away their tears in a desperate attempt to look forward. However, just as they were gradually regaining their normal lives, the next disaster struck the workshop.

In the summer of 2023, the workshop was hit by a massive landslide caused by heavy rain. Sand and muddy water poured into the workshop. The indigo jar and loom were damaged, and valuable materials were covered in mud. I think we may be doomed. ……,” she said. Seeing his mother’s despondent look, Takahiro also felt a complete loss of hope.

Immediately after the disaster, the two were at a loss. Soon, however, Takahiro’s friends from his days as an office worker, as well as Kurume City and Oki Town officials involved in the protection of cultural properties, arrived to help clean up the workshop, and the two gradually regained their composure. The two gradually regained their cheerful spirits. “The production of Kurume kasuri is a self-contained process, so sometimes there are moments when we feel lonely,” said Mr. Takahiro. However, the disaster made us realize once again that we have the support of many people.

Now, I am also pursuing the theme of “light,” which my father had set as the theme of his work. I am trying to dye not only with indigo but also with yellow, green, and various other colors of plants and trees. I would like to find my own unique way of expressing Kurume kasuri by getting various hints from nature, such as the wind blowing in the mountains, the murmuring of rivers, and the sound of leaves rustling in the wind. Takahiro’s journey of exploration continues, using the light left behind by his father, Tetsuya, as a guide.