Gunma Prefecture has developed as a country of sericulture. Takasaki City, in particular, has a history of the development of dyeing techniques, as when Ii Naomasa, the lord of Minowa Castle, moved to Takasaki Castle, dyeing artisans also moved with him. In Takasaki City, Gunma Prefecture, there is a workshop that dyes Edo komon. It is Aida Senko Co., Ltd. established by Masao Aida, the predecessor of the company. Currently, his apprentice, Aida Airo, has taken over the business and continues to produce works that convey the tradition, technique, and spirit of Edo komon.

Creating Edo komon that live on today

Aida Dyeing Co., Ltd. in Takasaki City, Gunma Prefecture, is a workshop that carries on tradition and craftsmanship in the field of “dyeing” in Gunma Prefecture, where industries related to silk fabrics have developed.

His predecessor, Mr. Masao Aida, who honed his skills as a migratory craftsman and returned to Takasaki to establish Aida Dyeing Co. in 1977, was recognized as an important intangible cultural property holder designated by Gunma Prefecture, and was awarded the Order of the Rising Sun in 2011 and the 60th Commemorative Award at the 60th Japan Traditional Crafts Exhibition in 2013, as the leading expert on Edo komon In 2013, he received the 60th Commemorative Award at the 60th Japan Traditional Crafts Exhibition. At the same time, he devoted himself not only to training successors of Edo komon artists, but also to training successors of Ise-katagami, an essential part of Edo komon.

After Masao passed away in 2017, his apprentice Airo Tanaka inherited the name and techniques of Aida, and under the name “Aida Airo” continues to make products that convey the beauty of Edo komon made with Isekatagami and the excellence of hand-dyeing. Just as his master Masao did, Airo is also creating works that blend in with the lifestyles of modern people.

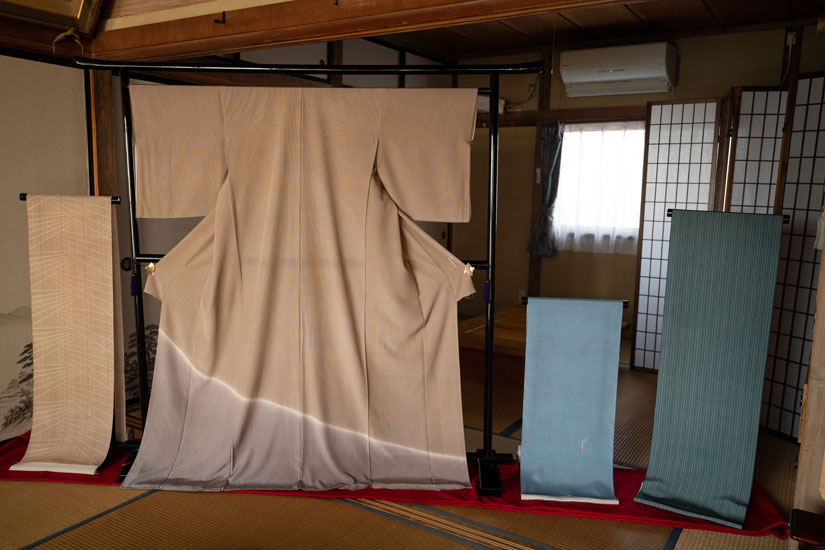

Precise and delicate Edo komon

Compared to woven fabrics, in which the threads are dyed first and the pattern woven, dyed fabrics, in which the fabric is dyed afterward, can express more delicate patterns. Among these, the Edo komon, dyed using the katazome technique that has been handed down from the Edo period (1603-1868), uses a particularly precise and detailed pattern paper. It is said that a high level of skill is required to dye patterns so fine that they appear plain from a distance, and the finer the pattern, the higher the value of the dyed item.

It is said that the Edo komon originated in the Edo period (1603-1867), when samurai wore a plain kamishimo (kamishimo) with a clan pattern on it as a samurai’s kamishimo (kamishimo).

Since the Meiji period (1868-1912), the Edo komon has gradually changed to reflect the times. With the motto of “not only valuing tradition, but also creating Edo komon that matches the times,” Airou’s master, Masao, started blotch dyeing himself and devised his own unique technique that went beyond mere dyeing.

Collaboration with a stencil carver

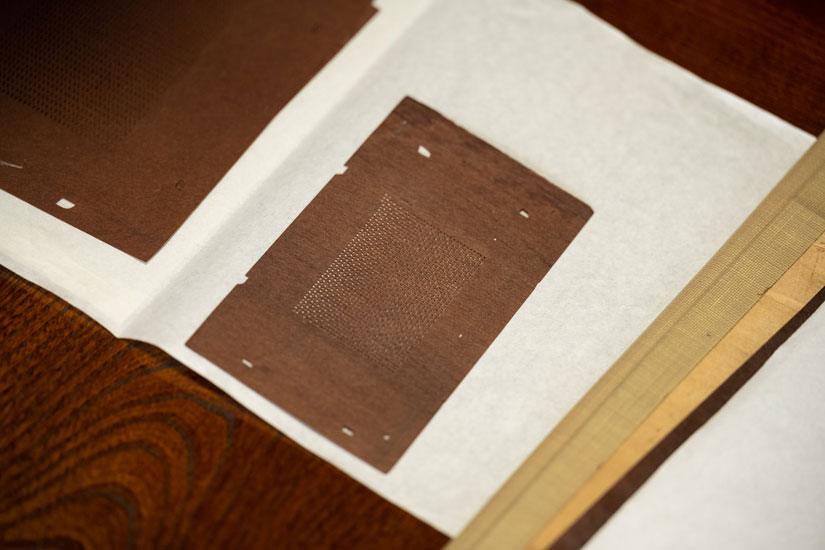

In the workshop, all the processes of dyeing Edo komon are done by hand using the precious Ise-katagami inherited from Masao.

Before his death, Masao once said, “An Edo komon artist has no skill.

Even if an Edo-komon artist has the skill, he cannot do any work without katagami. I think it is my mission as a craftsman to preserve katagami for the next generation and to encourage katagami carvers in Ise to make as many katagami as possible.

True to his words, Masao frequently visited Shiroko-cho, Suzuka City, Mie Prefecture, where Ise katagami is produced, and even begged Mr. Hiroshi Kodama, a living national treasure, to make katagami for him. Later, he received valuable katagami from Kodama and asked a kata carver in Shirako-cho to make the katagami he wanted, thereby nurturing and preserving the valuable katagami techniques essential to Edo komon.

Fascinated by the charm of Edo komon

Mr. Aida Airo’s first encounter with Edo komon was at his coming-of-age ceremony. She was drawn to the charm of Edo komon after attending a coming-of-age ceremony wearing an indigo-dyed Edo komon kimono and haori, dyed by Mr. Aida’s mother, Masashi Naka, who is the youngest brother of Mr. Aida Masao.

I didn’t know anything about kimonos at the time, but I remember that the kimono I wore for my coming-of-age ceremony was very comfortable and it was the best day of my life,” she said.

Unable to forget the excitement he felt at that moment, after graduating from college, he knocked on the door of Aida Dyeing Co. and became Masao’s apprentice. He spent his apprenticeship watching his master’s back, learning the techniques of the heart, and sincerely confronting himself.

He says, “I learned not only technical skills, but also the practical use of the master’s experience.

It did not take long for Airou, who quickly absorbed Masao’s teachings, to emerge as a master of Edo komon, thanks in part to his natural sense of style and dexterity.

What I want to express in the age of 2025

Inheriting Masao’s belief that “what we make must be used in accordance with the times,” Airou is also actively challenging himself to create new works while preserving traditional techniques.

In 2025, when fewer people wear kimonos on a daily basis, Mr. Airou wants to create items that go well with both Japanese and Western clothing, and he is taking on new challenges, such as dyeing an organdie stole with Edo komon (a traditional Japanese pattern).

My master told us to think about what we, living in that era, want to express now. At the same time, he also told us that we cannot express anything unless we have the basics.

He was taught that, as a craftsman, he should be able to express what he wants to express only when he has the skills to dye whatever he is asked to dye.

One of the most important messages that Masao has passed on to me is that when I receive an order to make something like this, I should not become a craftsman who says, “I can’t do it.

The pattern will break someday.

Edo komon requires a steady and precise technique, as a single pattern is used 70 to 90 times to dye a single piece of cloth. At the same time, the katagami must be able to withstand such a large number of uses, and it is important that the stripes are not crushed and that the glue is applied evenly and cleanly.

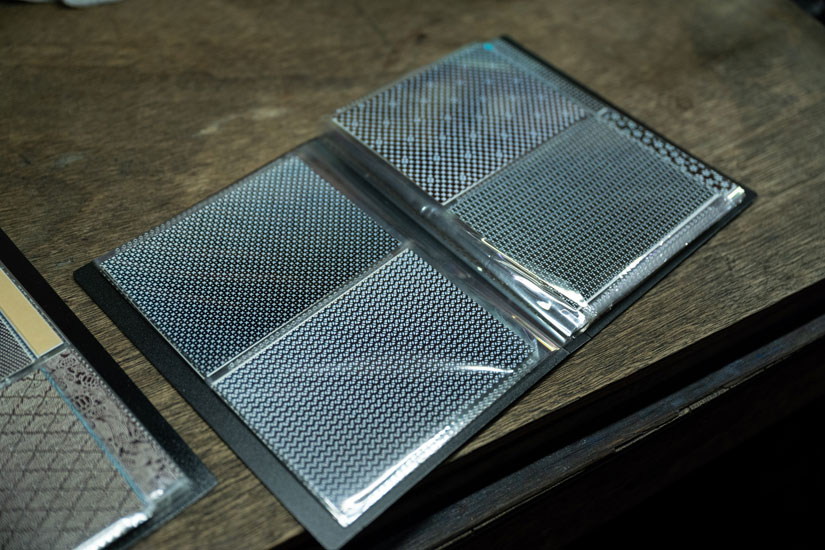

Ise katagami used for Edo komon is made of strong and well-preserved Mino washi coated with persimmon tannin, and patterns and designs are carved on katagami made by pasting three or four layers of alternating longitudinal and transverse fibers together to increase the strength of the paper.

The shimabori technique is so delicate that only a few craftsmen are able to carve it, and the aging of katagami craftsmen and the lack of successors have become serious problems.

Aida Dyeing still has many of the valuable Ise katagami that Masao raised and protected. If used, they become worn and their durability deteriorates, and one day they will break and become unusable. When dyeing Edo komon, Airo takes great care not to put too much strain on the stencils and trusts in his own skills.

While preserving traditional techniques, he also challenges new expressions.

Masao Aida, who has mastered the Edo komon technique in dyeing, served as a member of the judging committee for the “Japan Traditional Crafts New Works Exhibition” and the “Japan Traditional Crafts Dyeing Exhibition” during his lifetime, and has worked hard to pass on and develop the Edo komon technique while building a close relationship with pattern makers. Having witnessed Masao up close, Airou says, “One day, I will be able to see the precious kata in his workshop.

I would like to use the valuable katagami in the workshop in a way that I am satisfied with,” he said.

Some of the katagami in the workshop are so elaborate that one wonders if there are craftsmen in the world who have carved such katagami. Looking at such formidable katagami, one gets excited just thinking about how they can be used to create interesting works of art. At the same time, he says that the fact that such katagami are still in the workshop makes him feel great appreciation for his master’s greatness and his achievements.

Dyeing organdie with Edo komon

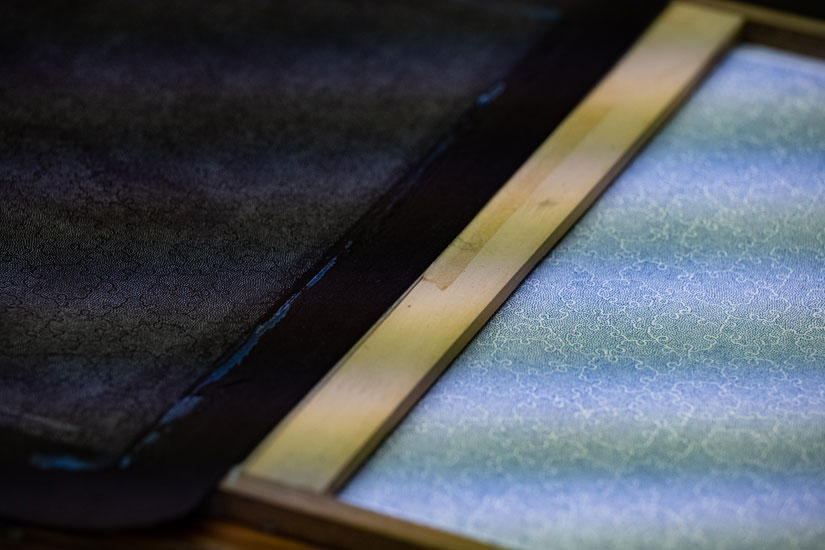

In addition to traditional Edo komon kimonos and fabrics, Airou now produces scarves made of 100% silk organdie, dyed with a single pattern to avoid monochromatic colors.

Thin and soft organdie cannot be patterned unless it is attached to a board. The fabric is so thin that at first it tore.

At first, it was difficult to peel off the board because it tore, and the lightness of the fabric made it easy to slide off the board, and it also made it stick. We then devised the quality and quantity of glue and the method of application, and finally succeeded in attaching the Edo komon pattern to the organdie.

For Edo komon with fine patterns, the artisan’s skill is to dye the pattern so beautifully that the seam between the pattern and the mold cannot be seen. The same is true for thin and light organdie. After successfully applying the Edo komon to organdie, Airo used the patterns in his workshop to add various colors and patterns.

I think this is also Edo komon of 2021.”

Making things that are used by people according to the times

While preserving the traditional dyeing techniques of Edo komon, Airo is now taking on the challenge of new expressions.

I believe that culture must change along with the changes in our lives, because culture is something that is connected to the way we live at a given time. I think it is important to create works that people want today, not just to change nothing because they have traditional value.

While preserving traditions, such as dyeing on thin fabrics, the company is also working to develop new techniques for materials and dyeing. Living in 2038, he says that they need to make not only traditional Edo komon kimonos, but also stoles, pocket chiefs, and other items that match the times. From the works created by Mr. Airou, one can feel the “iki” of Edo that is in tune with the times, which can only be expressed by a craftsman with traditional skills.