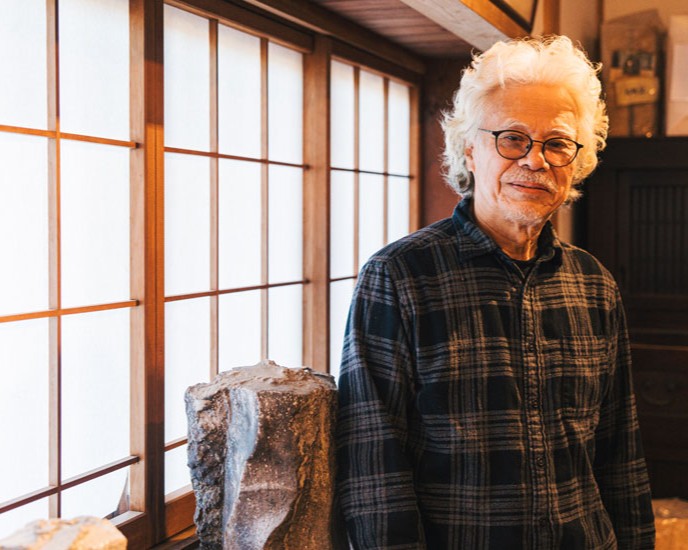

Mr. Ken Matsuzaki is a ceramic artist whose teacher is Tatsuzo Shimaoka, a so-called Living National Treasure and holder of the Important Intangible Cultural Property technique for ceramics. He learned Mashiko pottery, which flourished as folk art pottery, under Mr. Shimaoka, and thought he would go straight into folk art, but his style went in a completely different direction. He began by thinking, “This looks interesting,” and then asked himself, “How can I do this?

Works created by “doing what I wanted to do” in Mashiko

It has been about half a century since potter Ken Matsuzaki, who has been active not only in Japan but also in other countries such as New York, Boston, and England, opened his “Yushin Kiln” in Mashiko Town, Tochigi Prefecture. Among the wide variety of pottery produced by Mr. Matsuzaki, his “Anagama Yohhen” pottery, fired in a primitive, wood-fired anagama kiln and featuring accidental colors produced by the kiln’s flames, is particularly powerful and striking.

Why was Mr. Matsuzaki, who seemed to have mastered the folk art under Living National Treasure Tatsuzo Shimaoka, attracted to kiln-change?

Mashiko, home of ceramics

The hilly town of Mashiko, located on the border of Tochigi and Ibaraki prefectures, is famous throughout Japan as the “Mashiko pottery production area. In the late Edo period (1603-1868), the lord of the Kuroba domain granted land to Mashiko potters, who steadily increased their production, and Mashiko Pottery became a “go-yo-gama” (a kiln under the control of the lord). The term “imperial kiln,” in the broadest sense of the term, refers to a kiln in which the clan assisted the potter and ceramic industry by protecting and fostering it. After the Tokugawa Shogunate disappeared with the Meiji Restoration and the prefecture lost its patronage due to the abolition of feudal domains, each kiln began to operate and expand its sales channels. Mashiko ware was produced as daily necessities such as braziers, mortars, kettles, and cauldrons.

Recognized as a Living National Treasure by Mashiko Pottery

In Mashiko, there was Shoji Hamada, who was recognized as the first holder of the Important Intangible Cultural Property (Living National Treasure) in 1955. Mr. Hamada was a central activist in the “folk craft movement. In addition to Mr. Hamada, there was another person who was certified as a Living National Treasure. Mr. Matsuzaki’s mentor, Tatsuzo Shimaoka. He became interested in folk art after visiting the Japan Folk Art Museum, and in 1940 he became a student of Hamada’s. In 1954, he opened a kiln in Mashiko and began to make pottery in earnest.

Influenced by his father, he became familiar with folk art at an early age and eventually became a potter

Mr. Matsuzaki says his father was a Japanese-style painter and folk art collector. Since he was a child, he has been surrounded by objects from the Edo and Meiji periods, and was excited to see them being bought and sold when he was taken to antique fairs. Perhaps because of his father’s influence, he became fascinated with ceramics after using a potter’s wheel in a high school art class.

Career path changed at the recommendation of a high school teacher

A ceramics class encouraged Mr. Matsuzaki to enter an art course, and he enrolled in the Tamagawa University Art Department, majoring in ceramics. He finished his assignments early and competed with his friends to see how many teacups he could make in an hour, grinding more than 20 of them on the potter’s wheel. He learned the basics of the potter’s wheel by the time he was a freshman in college. Matsuzaki analyzes himself as “an artist and a craftsman,” and the sense of speed he acquired during his college years is now utilized in the craftsman part of his work.

Studied under Tatsuzo Shimaoka

He decided while still in college to train under Tatsuzo Shimaoka, who was an acquaintance of his father’s, and became his apprentice after graduation. During the three years he was promised and the two years he was given to extend his training, he was able to learn from Mr. Shimaoka the importance of a philosophical approach to ceramics and the attitude one should take when creating something.

During the additional two years, he made his own original tableware, studied patterns, and experimented with white-lacquered mud, and by the time he became independent, he had his own style. The Gosuyuu-sagimon, Shirogake-senmon, Tetsu-ji Hakeme-mon, Ao-ji Hakeme-mon, Budou-mon, Usagi-mon Tsutsugakiryu-sui-mon, and other original patterns created during this period would support Matsuzaki for the next 15 years. Matsuzaki’s original designs would sustain him for the next 15 years.

Away from Mr. Shimaoka and trying what he wanted to do

After becoming independent, Matsuzaki thought he was making good progress, but one day, when an overseas art professional called his work a “copy of Mr. Shimaoka’s,” he was prompted to ask a question he had never considered before. Since then, he has been thinking, “The glaze and shape are similar, only the pattern is different. Then, when the pattern is changed, whose work is it? I could not even get any work done. He then began to struggle to master new techniques, for example, switching from the potter’s wheel and mashiko materials he was using at the time to hand-binne (hand-painted pottery).

Learning from Oribe Furuta’s philosophy

Mr. Matsuzaki decided to distance himself from the techniques and style he learned under Mr. Shimaoka. Soon after, he began to find Furuta Oribe’s philosophy and Oribe’s style interesting, considering it to be a “Japanese renaissance. Furuta Oribe was a warrior of the Momoyama period and a famous tea master. Oribe, which bears his name, is a pottery characterized by its innovative shapes and designs, and the name derives from his fondness for the patterns, shapes, and color tones of his pottery.

While learning the basics of the Oribe style, Mr. Matsuzaki independently interpreted the energy that spread the Oribe style from Kyoto to the west at once, and went through a series of trial and error, considering Kizeto, Setoguro, and even Shino as Oribe. He believed that by experimenting and learning what he was interested in without having a master, he would obtain a style that was not an imitation. He started without telling his master, Mr. Shimaoka, and lost contact with him for about two years after he became known to Mr. Shimaoka. He says he felt much better when Mr. Shimaoka said to him, “I would have excommunicated you, but you told me to go to .

From 1978, he held a solo exhibition at the Shinjuku branch of Keio Department Store every year, which was well received and gradually led to solo exhibitions not only in Japan but also in New York, Boston, and the U.K. In 1980, he was invited to exhibit at the National Exhibition Hall in Tokyo.

In 1980, he was awarded the Nojima Prize at the National Exhibition of Japan, and in 1984, the Yusaku Kaiyu Prize at the National Exhibition of Japan. He has won a number of prestigious awards.

Feeling the energy of the soil without setting an end point

In the world of ceramics, where many people stick to one technique, he creates his works with the idea that he should be sensitive to various things and constantly change. Matsuzaki says, “There are not many people who do as many different things as I do, but I can only do it that way. However, I have always sought the energy of soil. When he encounters interesting clay, he thinks, “I wonder if I can somehow express it,” and then he thinks, “I can’t wait to make it into a vessel. His attitude of starting a new experiment when he thinks something is “a little interesting” is still alive and well.

A style that has been discovered, and will continue to be discovered

As times change, what is required may also change. We accept change and change ourselves. He launched GENDO, a project to create vessels with a new interpretation, which is created by a Mashiko artist and a chef. The designs of the vessels are different from his usual style, but Matsuzaki, who says he is both an artist and a craftsman, says that the craftsman part of him comes out and “it’s fun to do.

Never-ending challenge because it is always unfinished

When I get new clay, I get excited thinking about what I’m going to make and where I’m going to put it in the anagama and fire it.

I think I will do what I want to do until the end. I continue to take on various challenges. It’s not like I’m trying to find a landing place, so I’m fine with the work being unfinished for a long time.