Hirudani, Asahi Town, Toyama Prefecture, is a small village by a creek that originates from Mt. There is only one washi craftsman who has inherited the “Birudani washi” that was born here about 400 years ago. He is Mr. Takakuni Kawahara of Kawahara Seisakusho. Mr. Kawahara handles everything from growing the raw materials to making the paper by himself. His unique ideas and sense of style are now attracting attention not only in Japan but also from around the world.

Traditional Japanese paper making, taught orally by a master in his 80s

The origin of Hirutani washi paper dates back to about 400 years ago. People from Hiru Valley in Higashiomi City, Shiga Prefecture, moved to Asahi-cho, Toyama Prefecture, near the border with Niigata Prefecture, and named the area Hiru Valley after their hometown, where they worked in the mountains in summer and at home in winter. One of their winter domestic jobs was making washi paper. In the early Showa period (1926-1989), about 120 households made washi, and it was a major production center. Hirutani washi, carefully made from natural materials, is strong yet soft, and is said to be durable enough to be preserved for 1,000 years. Together with Yatsuo washi and Gokayama washi, also from Toyama, it is collectively known as “Ecchu washi” and is recognized as a traditional national craft.

However, Hirutani washi, which was often used for shoji paper, lost its luster as demand declined with the changing times. One day, a woman wanted to preserve Hiruya washi, so she learned washi making from a papermaker and revived it. After falling ill, her husband, who was over 60 years old at the time, learned the art of papermaking orally from his sick wife, who had been making the paper for over 20 years. Just as the light of Hirutani washi, which the couple had been preserving for more than half a century, was dying out, they met a young, 23-year-old Mr. Kawahara.

Torakichi Yoneoka was 83 years old at the time. However, Mr. Kawahara was moved by Torakichi’s way of life before, during, and after World War II, as well as his sincere approach to washi making, and decided that he would like to carry on Mr. Yoneoka’s ism.

He was so moved by Yoneoka’s life and his sincere approach to washi making that he wanted to carry on Yoneoka’s ism. “I was determined not to let my hometown culture die out,” he said. Despite repeated failures, Kawahara diligently learned the traditional Hirutani Washi manufacturing method and papermaking techniques with his body.

There is no future in simply preserving tradition. We need to create products that do not depend on the place of production.

At the time, however, traditional crafts were tapering off, Kawahara says. When I was working alone, I suddenly realized that it was not a matter of preserving traditional culture. It was not a question of preserving traditional culture. Washi itself is a declining industry. Older people have pensions and can continue to do it as a hobby, but younger people can’t do it. If you look at the history of washi making, it was something that people did only during the winter months while making a living. It was impossible for them to make a living with just washi.

For a while, he worked part-time at a zoo in Toyama City and at a local office, while still being involved in washi making. But he was able to continue because of his conviction: “Don’t just fall in love with washi. It is okay to do various things while making washi,” his teacher told him.

One of the answers that Mr. Kawahara came up with in the face of washi was to venture out of the production area. One of the answers he came up with was to go out of the production area. However, the time has come when people no longer choose washi because it is made in a particular place. It would be great if washi could be made in a variety of places and craftspeople could play an active role, regardless of where the paper is made. I thought it would be interesting to see people making washi that is not bound by tradition.

As long as you have the technology, you can make paper anywhere. The era of “one-man production centers” will surely come in the future. As a pioneer, I would like to try various things. With this in mind, Mr. Kawahara left Asahi-machi and moved to Tateyama-machi after his master passed away.

In a peaceful village, he grows his own raw materials and makes washi paper from scratch.

I want to do it from scratch in as small a place as possible. I wanted to put aside the title of “traditional” in order to make washi in my own style,” he said. Mr. Kawahara chose the Mushitani area of Tateyama Town, a small community with only 14 private homes.

First, he cleared the mountain and planted 700 kozo (paper mulberry) plants, the raw material for washi, on a gentle slope. They then rented a nearby field and grew tororoaoi, a mallow tree that is essential for making washi, or “neri. He took over a vacant house that used to be a farmer’s barn, renovated it, and turned it into his workshop. At the same location, his wife, ceramicist Sakae Nagayo, also has a studio where she makes ceramics.

From April to November, he works in the mountains and fields. In the spring, he sows seeds of tororoaoi, and in the summer, when the flowers bloom, he picks them one by one to nourish the roots, which will be used as a mucilage. In the fall, they go into the mountains to cut off the branches of straight-growing mulberry trees and steam them in the workshop to soften them before peeling off their skins. The temperature and time of steaming are adjusted according to the condition of the branches and based on past experience. Once the skin is removed, the surface is scraped off, leaving only the inner white part, which is then dried in the sun.

By the way, it is said that there are only a few washi makers in Japan who grow their own kozo and tororoaoi, but Kawahara’s involvement in cultivation is both characteristic of Hirutani washi and a reflection of his concern for the future of washi.

I read an article in the newspaper once that farmers in Ibaraki Prefecture are going to stop growing tororoaoi, and I heard that if the five tororoaoi farmers disappear, there will be a shortage of 80-90% of the raw material for handmade washi in Japan. This is a crisis for the washi industry. If we depend on someone else, if that person goes bankrupt, we will also go bankrupt. There are cheap Kozo paper from overseas, and many craftsmen rely on imported products. However, it is better to procure one’s own kozo from the mountains near one’s home,” says Mr. Kawahara.

With the arrival of winter, the papermaking process finally begins. The process of making washi from kozo (paper mulberry) and tororoaoi (Japanese mallow), which are grown with great effort and care, makes the process even more intense.

In the workshop, a large kiln inherited from his master is heaving with steam.

The process of making washi involves boiling kozo (paper mulberry) in a kiln, washing it in water, beating it with a mallet, making the paper, weighing it down to drain off the water, and drying it (……). In most cases, these processes are carried out under the division of labor, but here Mr. Kawahara carries out the entire process by himself. For this reason, he changes the work he performs each day.

When boiling kozo in a kiln to remove the lye, he uses firewood. It is a time-consuming process, so we start boiling in the evening and boil it in the morning. The firewood keeps the fire hot for a long time, and the fire source is safe even if you are not near the fire. It’s more rational than sticking to the old-fashioned style.

While every step of the process requires careful attention, what is especially important is the process of pounding the paper mulberry with a mallet. If the paper is beaten well, it becomes fine-grained washi, and if it is beaten roughly, the fibers become more prominent. Because the texture of the paper becomes so different in this process, it is important to have a clear image of what kind of washi you want to make and what the finished product will look like.

Full customization to create the washi required by the customer.

Mr. Kawahara does not sell what he makes, but makes washi completely on a made-to-order basis. When he had mastered the art of papermaking, he once went to paper wholesalers and specialty stores to sell his products. But he realized that the washi he made himself, which he made by gathering kozo (paper mulberry trees) from the mountains, getting covered in mud, and putting his own hands and salt to it, was very precious to him and was not something he could sell with his head held low.

What do you think makes good washi? It is not something that was made in a particular place or by a traditional method. Good washi is what is easy to use and what the person is looking for.

In this way, Mr. Kawahara pursues what sticks in people’s minds and focuses on making washi not as stationery, sundries, or folk art, but as a craft and art. He has established a unique technique and method of expression by layering ultra-thin sheets of washi to make designs and patterns appear through the layers.

After receiving numerous awards, including the Silver Prize in the Toyama Traditional Crafts Competition, the company began to receive orders from various fields, such as the entrance exhibit at the Japan Expo in Paris, the presentation of a city emblem made of washi to the mayor of Florence, the interior of the Kurobe Unazuki Onsen station of the Hokuriku Shinkansen Line, and the walls of the TOYAMA Kirari, designed by Kengo Kuma The Toyama Prefectural Citizen’s Hall lobby interior.

For the order of washi paper for the lobby interior of the Toyama Prefectural Citizens Hall, he mixed mulberry bark with Tateyama cedar bark and combined it with glass, another Toyama specialty, to create a beautiful ooze of Tateyama-like hues.

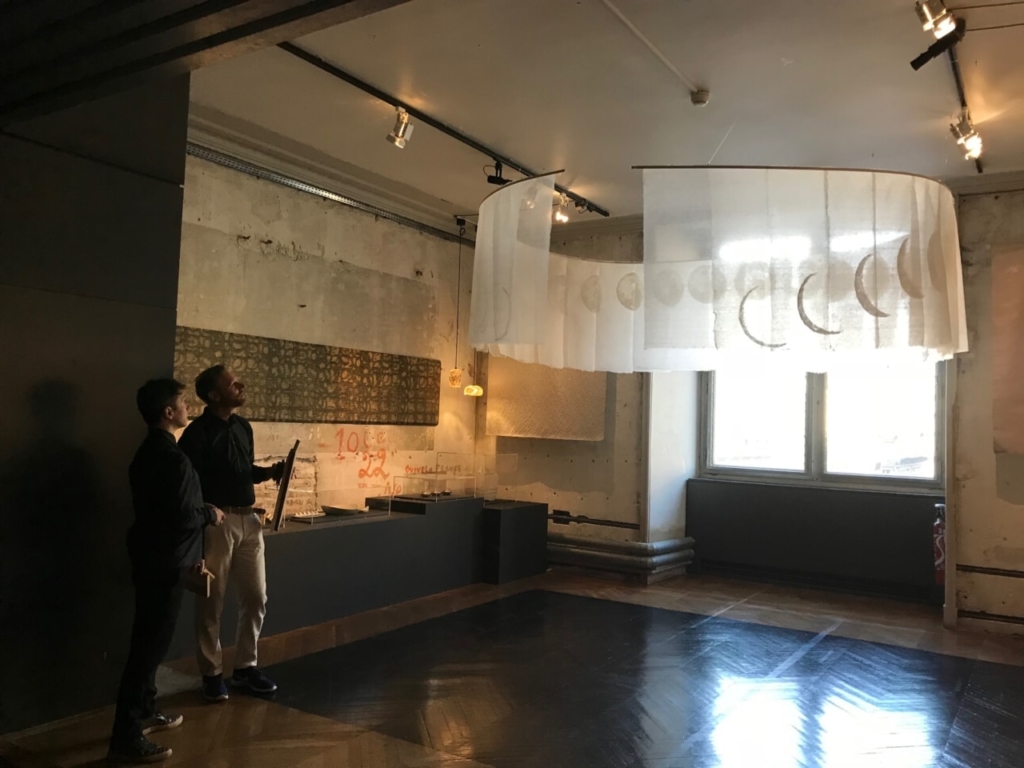

In 2017, he won the Grand Prize at the U-50 International Hokuriku Awards. The following year, he was invited to an event at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs at the Louvre in Paris, where he exhibited a fantastic washi paper work on the theme of the phases of the moon. The transparent thinness and unique texture of washi, not found in any other material, fascinated people around the world.

On the other hand, “Tateyama Goyou (talisman for Mt. Tateyama),” which is given at New Year’s at the Oyama Shrine in Ashikuraji, which is rooted in the Tateyama faith, is also something that Kawahara-san makes every year. The design is based on the Edo period woodblock prints and is hand printed one by one on handmade Japanese paper. It is sure to be a memorable and appreciated piece of paper for the local people.

The Potential of Washi Expands through Encounters with Expressionists

One of his recent masterpieces is the wall artwork in Tokyo’s Toranomon Global Square. Kawahara’s washi work decorates the entire wall of the escalator directly connected to the subway station, and the permanent installation of this large-scale washi, covering more than 200 square meters, is an unprecedented attempt in the world. The light-permeating washi paper gives the inside of the paper the appearance of being softly illuminated like a paper lantern.

At the reception desk of the main entrance is a magnificent piece of washi paper with contour lines of the Toranomon area made of 12 colors of colored threads. The paper was made using a special mold frame to create a single sheet of paper measuring 3.5 meters in length by 10 meters in width. The work required not only the creation of something large, but also a great deal of technical ingenuity. I had a lot of discussions with the building’s designers to see what kind of thing we could create, and I thought it would be interesting to create contour lines that were unique to the area. Eriko Horiki, a Japanese paper artist, was also involved in the direction of the design, and we worked together on the colors and other aspects.

Kawahara says that what he would like to do in the future is to team up with a chef, such as a French master. It would be nice to use carrots, spinach, or other ingredients to make washi paper,” he says. I want to be the kind of person who people think, ‘If you ask this person to create an interesting space,'” he says with a twinkle in his eye. He will continue to meet designers, architects, and chefs (……) and multiply their ideas. He will continue to meet with a variety of people and multiply their ideas. He will incorporate new ideas that cannot be found anywhere else into the essence of Hirutani washi, which he has single-handedly inherited from his master. From Toyama to the rest of Japan and to the world, traditional washi will spread its wings. The challenges to achieve this goal are endless.