Starting with preparing the clay

Bizen-yaki has a long history. It is said to have begun in the late 12th century, and is counted as one of the six old medieval pottery representing Japan.

Having such a long history, Bizen-yaki is so simple that it can almost be considered ”blunt”. No glaze is used and there are no designs. Only shaping the clay and baking. In spite of such simple methods, Bizen-yaki ware possess a deep allure.

First, there is the preparation of clay. With Bizen-yaki, earth from rice fields, mountains, and black earth is mixed and left to rest for several years. Skills such as determining how long the clay is left to rest and the make-up of the clay can influence the quality of the clay. When the fine, sticky Bizen soil is allowed to rest for several years, microorganisms grow producing more than 80 kinds of yeast. When the clay is baked, it results in beautiful pottery with an almost moist texture.

Baked at high temperature for long periods

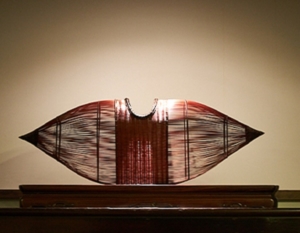

There is also a color variation called “yohen”. Bizen-yaki is baked in a kiln at 1300 degrees Celsius for 2 weeks. The part buried under the ashes becomes black or blue while the part exposed to flames turns red ochre. The color may depend on how the pieces are placed in the kiln, but coincidence is a large factor making no piece identical. The patterns which emerge from this process can even seem majestic.

Nakata visited Living National Treasure Jun Isezaki, and was shown Bizen-yaki pottery with these features. Born in 1936, Isezaki was designated a Living National Treasure in 2004. His works are displayed in museums and the lobby of the Prime Minister’s Official Residence. Nakata received a lecture about Bizen-yaki in front of a kiln, and also experienced kneading clay.

Bizen-yaki created by the interaction of clay and fire, is in a sense a small universe created by the unity of nature and people.