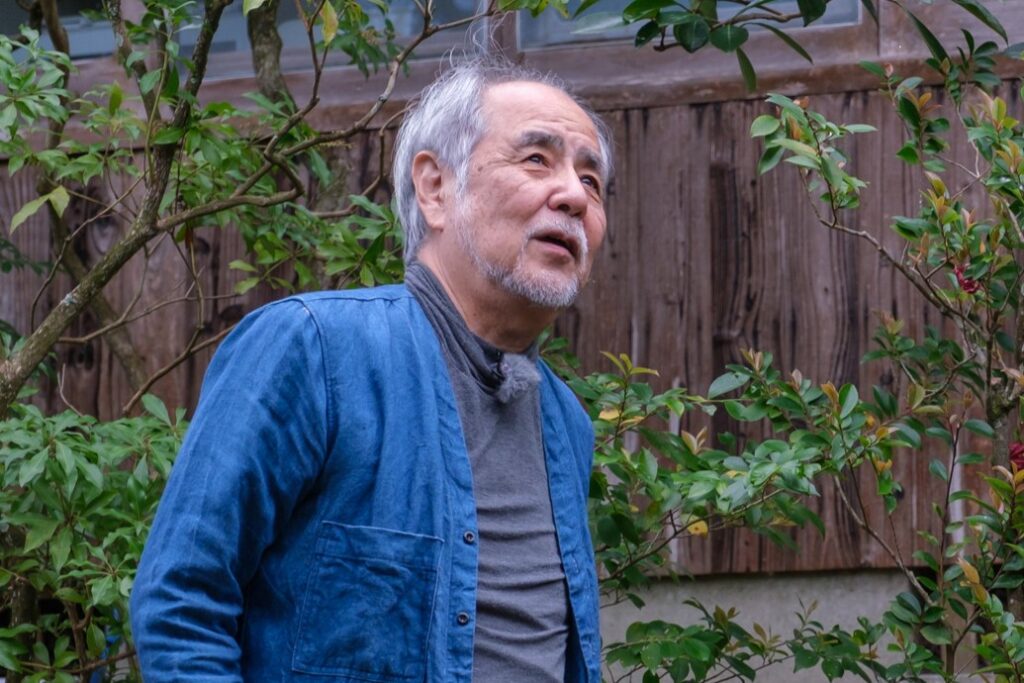

Hagi-yaki is a renowned tea ceremony ware that has been described in the tea ceremony as “Ichiraku, Ni-hagi, San-karatsu” (one for Raku, two for Hagi, and three for Karatsu ). The 15th generation of the family, Shinbe Sakakura, is the keeper of this venerable kiln, which has roots that go back more than 400 years to the time of Hagi ware’s inception. He is an artist who continues to challenge new possibilities for Hagi ware with his unique style, using both traditional techniques that bring out the unique charm of Hagi clay and cutting-edge expressions.

The History of Fukagawa Hagi, One of the Old Streams of Hagi Ware

Nagato Yumoto Onsen, located in the mountains of northwestern Yamaguchi Prefecture, almost at the western edge of Honshu, is the oldest hot spring resort in the prefecture, with a history dating back several hundred years to the Muromachi Period. Leaving the hustle and bustle of this popular hot spring resort, which still attracts a constant stream of tourists, visitors can proceed down into the valley to an area called Sounose, where the potters of Fukagawa Hagi, a prestigious Hagi-yaki pottery family, live.

Protecting the kiln for 400 years since the founding of Hagi ware

Hagi ware has its roots in Koryo tea bowls, a type of pottery derived from continental culture when the Sea of Japan was the center of trade. 1605, Terumoto Mori, the ruler of China, invited potters from Koryo (present-day Korea), and for a long time Hagi ware was patronized as the official kiln of the Mori clan (another name for the Choshu clan), and in the mid 17th century, the kiln was established in Hagi In the mid-17th century, the kilns were moved from Hagi Castle to present-day Nagato City and Fukagawa. The Shinbei Kiln here is called “Fukagawa Hagi,” and it is a famous kiln that has continued for 360 years in this Fukagawa area, generation after generation.

Shinbei, the 12th generation, is known for finding new sales channels throughout Japan and preserving the name of Hagi ware for future generations at a time when Hagi ware was in the most difficult situation in its history due to the dissolution of the Choshu domain in the Meiji era and the loss of the feudal lord who had been its largest supplier. He is known as the “founder of the Hagi-yaki revival,” and was a key figure in spreading the name of Hagi-yaki in the modern era, as well as being the grandfather of the current generation.

Hagi Ware Tradition

Hagi ware is characterized by the use of a mixture of three types of clay: the white Daido clay, the reddish Mishima clay, and the iron-rich Mitake clay, all of which are mined in the Hofu City area of Yamaguchi Prefecture. The combination of these three types of clay, which have been used for generations, has many merits. The high content of gravel and sand prevents the clay from hardening, and the “rough” Hagi clay retains its original flavor. In addition, the lightness and ease of use as a tea bowl, as well as the durability and fire resistance of high-temperature firing in a climbing kiln that takes advantage of the steep mountain slopes, are also demonstrated.

The beauty of the surface cracks caused by the difference in shrinkage between the glaze and the clay, called kan-in (penetration), and the “Hagi no shichikake,” or “seven transformations of Hagi,” which refers to the way the bowl changes and grows more beautifully as it is used over the years, as matcha (powdered green tea) soaks into the cracks.

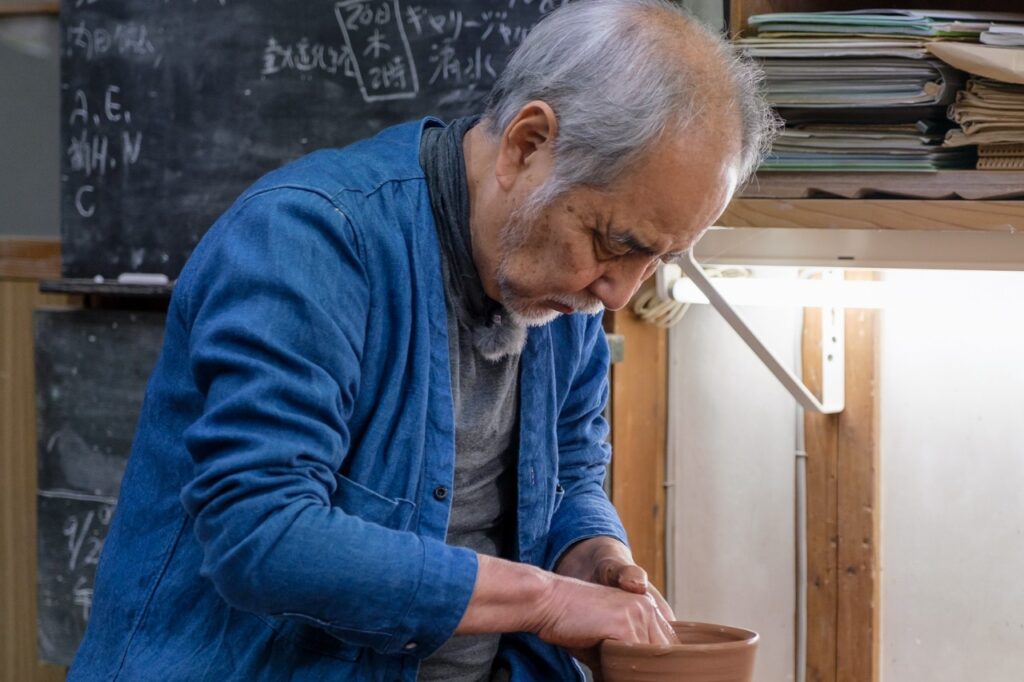

Shinpei-gama has inherited this extremely difficult-to-handle and difficult-to-form clay from generation to generation, and has preserved the “scenery created by the Hagi clay” and “earthy flavor” while maintaining a symbiotic relationship with it and its beautiful contours. In essence, the question continues to be, “Is the clay being used to its fullest potential? In particular, he pursues whether the “earthy flavor” of the clay is expressed in his pottery.

Tsuchiai” refers to the charm of the original clay that is expressed in pottery after firing. It is an expression in which the contrast between the simple and rough texture of the clay and the design of the decoration, such as glossy glaze, brush marks, and clay, is brought out as a synergistic effect of beauty. The power of the Hagi clay and the delicacy of the glaze create an odd contrast that captivates those who hold it in their hands.

As a potter and an artist who has inherited a long tradition

Mr. Shinbei Sakakura, the 15th generation of the current generation, is not only commissioned by tea masters from all over the country who seek tea ceramics of prestigious names, but also has his solo exhibitions held in various places in Japan, gaining popularity. He is a rare artist who creates innovative works of art while preserving the axis of “expressing the charm of clay” of Hagiyaki, which has been cultivated over many years.

In 2013, he was certified as a Yamaguchi Prefecture-designated holder of intangible cultural assets for Hagi-yaki pottery. He continues to create works that elevate the appeal of Hagiyaki to the realm of art, not only as tea ceremony utensils, and continues to propose figurative expressions that give Hagiyaki a new evolution.

His decision to enter the sculpture department of Tokyo University of the Arts was of his own volition, without the pressure of taking over the family business. However, soon after graduation, his father fell ill, and at the age of 29, he succeeded to the family name before he had time to catch his breath. Although he was only able to work in the same kiln with his predecessor, the 14th generation, for a few months in his later years, his three-generation life with his grandfather, Shinbei the 12th, until he was in elementary school, formed the foundation of his career as a ceramic artist. () The name Sakakura Shinbei XIII was given to his brother Kotaro, the 14th generation, who was killed in battle.

Hagi-yaki lost its largest clientele with the dissolution of the shogunate and domains following the Meiji Restoration. While each kiln needed to find new methods and sales channels, Hagi ware was not well known to the private sector, even in the kiln’s own neighborhood. The 12th generation was born at such a time of decline. Hagi ware was originally positioned as an official kiln of the domain, and it was not until the 12th generation, after the abolition of the domain, that the potter began to stamp his own seal of approval as an artist.

The 12th generation, with his dynamism and foresight, decided that he should send his works to the center of the country and to places with more people, so he would make a piece for six months and then go out with a large baggage for the remaining six months. He spent the remaining six months of the year making artworks, and then spent the rest of the year going out with a large pack on his back.

In particular, he frequently traveled to Kyoto, where the population of the tea ceremony was increasing at the time. He was initiated into the Urasenke school of tea ceremony, and under the guidance of his master, he produced many prestigious tea ceremony utensils as “Sakakura Shinbei” and established his reputation as a tea ceremony hagi (tea ceremony potter). In addition to being an excellent artist, he was also a producer and a great marketer, so to speak.

The influence of the 12th generation was so great that he said, “He has left a form for posterity in the form of his works. I respect him as a potter and as a human being,” he says softly and calmly.

It is precisely because the previous generations understood what the essence of Hagiyaki is, and passed down the tradition of preserving the basic principles, that today we are able to freely express ourselves and take on new challenges.

What is Hagi ware? Continuing to pursue the question “What is Hagi ware?

Hagi ware is popular in the tea ceremony because its minimal decoration and ease of use do not interfere with wabicha, the art of tea ceremony. The soft colors of the glaze, such as gentle white, pale pink, and the typical orange-tinged loquat color, as well as the comfort of holding the bowl, have made it a favorite of all generations. In recent years, Hagi ware has been used not only as matcha bowls, but also as elegant serving vessels for food in restaurants and ryotei (Japanese-style restaurants), as well as for daily use.

Clay: Hagiyaki “Tenohirano Scenery” is interesting precisely because it is nurtured.

In contrast to the beauty of the glossy glaze, Shinpei-gama tea bowls have a heavy appearance at first glance. However, the moment you hold it, you will be surprised at its lightness, and you will feel as if the tea bowl will fit comfortably in your hands.

He says that it is his greatest pleasure to be appreciated and appreciated by people who hold the tea bowls made by the traditional technique, saying, “It feels good in my hands” or “It feels comfortable when I lift it up. He says that the appearance of the tea bowl and the expression it shows when it is wrapped in the palm of one’s hand has a warmth that soothes people.

Kiln: “Improvisation” is the charm of Hagiyaki

Our generation says that the interesting thing about Hagi ware is its “improvability. The one-time use of clay and glaze that makes Hagi tea bowls unique can only be achieved in a climbing kiln, which is the most distinctive feature of Hagi ware. In the climbing kiln, pine firewood filled with oil is used to fire the bowls at a high temperature of 1,200℃ or higher all at once. Various surface changes, or yohen, appear each time the piece is fired, and the way the color appears and the glaze melts changes depending on where the piece is placed in the kiln. The kiln changes that are produced by the complicated kiln conditions unique to the wood-fired climbing kiln are what give the work its deep flavor, as well as the unexpected variations in pattern, color, and surface texture that are characteristic of Hagi’s traditional clay.

Because of this, no two pieces are exactly alike, and many failures occur. It would be better if only half of the pieces he bakes are ready for the world to see. Taking advantage of this feature, he challenges improvisational firing expressions by adding the oddities of firing results by mixing glazes and a further color change technique called “ash covering” during the firing process.

He says smoothly, “I can express yellow when fired with an oxidizing flame, blue when fired with a reducing flame, and the strange mix of colors when fired neutrally,” with a smooth tone that suggests his unstinting creativity and his enjoyment of experimentation.

He expresses the characteristics of Hagi clay and changes in glaze in each and every moment. Perhaps it is our generation that is most attracted to the improvisational charm of Hagi ware, which can be enjoyed as a chemical reaction.

Expression: A radical technique that makes use of Hagi clay as a point of reference

An insatiable pursuit of making the most of the “earthiness” of Hagi ware. This generation wanted to make the Hagi clay stand out even more. This is a form of figurative expression that he began in his 30s. The design of adding fine incisions in the form of stripes adds a roughness to the surface of the clay, while at the same time giving an impression of precision. In the case of his “kakegami” vases, the contrast created by layering two or three different types of glazes on top of the base clay creates a somewhat modern atmosphere.

Painting knives used in oil painting

Painting on Hagi ware was an unusual technique at the time. Flowers were painted not with paint, but with a heaping of decorative clay, and a painting knife was used, which was unusual for ceramics.

He also adopted a technique called zogan (inlaying), in which the clay is pasted on the surface while it is still in the raw drying stage to bring out beautiful pictures in three dimensions, and continued to make prototypes and think about ways to sublimate Hagi clay. The lilies, camellias, and irises that float in the rugged colors of the Hagiyaki base express a natural beauty, as if one’s eyes suddenly come into contact with wild flowers growing wild.

The glassy transparent glaze is applied as thinly as possible to bring out the three-dimensionality of the underlying clay surface and the painted relief-like raised clay, so that the unevenness of the clay appears honestly. In order to dynamically express the beauty of the kiln change, the vessels are placed near the fire and covered with ashes to about half the depth of the vase, creating a rich expression of the vase’s skin and surface. The contrast between the clay and the expression is fascinating.

The Origin of His Creative Motivation and Thoughts for the Future

The current generation hopes for the future of Hagi ware, not only for the family and the kiln itself, but also for the further prosperity of the Hagi ware culture itself. The reason for this is that he considers his grandfather, the 12th generation, who brought Hagi-yaki out of its current predicament and accelerated its popularity, as the starting point for his creative aspirations.

He says he wants to continue to preserve the reputation and dignity of today’s Hagi ware, which was gained through his grandfather’s skills and efforts.

Inheritance and Passing on to the Next Generation

The population of Hagi potters is not large, and there are no specialized schools in the local area, such as the Ceramic Research Institute in Kyoto, so they inevitably go outside the prefecture to study. The diversity of learning gained from studying in Tokyo and Kyoto and engaging in friendly competition with other artists of the same generation has been applied to the expression of Hagi-yaki pottery today. Today, as in the past, he shares his kiln with his eldest son, Masahiro, now in his 16th generation, and his grandchildren can be seen near the kiln.

Exchange with the Raku Family in Kyoto and Further Challenges

In addition to presenting his traditional works as an artist, he also actively promotes his works as crafts and art. A representative example is “Yoshizaemon X (X) Shinbei no Raku: Kichizaemon no Hagi” held at the Sagawa Art Museum in Shiga Prefecture in 2016. Some of you may know that it was a hot topic at the time.

This is an art collaboration between two of the current owners of one of Japan’s most famous kilns. Raku Kichizaemon (Naoiru), the 15th generation of Raku ware artist, happens to be an alumnus of the Raku Ceramics Department of the University of the Arts, and they still have a close relationship, including family dinners. Despite the buzz and attention in the art world, the collaboration of the century took several years to realize, and both Raku and Raku Kichizaemon greatly enjoyed the experience of working with each other’s clay in each other’s kilns. The experience of making things in a fresh environment was full of new discoveries, and it was like returning to the mind of a child. The stimulation of creating and presenting each other’s works in different firing methods, Raku ware and Hagi ware with different shrinkage rates, and in each other’s studio, must have influenced not only the artists themselves, but also their friends who were present, the audience, and above all, the young ceramic artists who came after them.

The phrase ” one million, one heart” is written as“one day, one power, one heart. This phrase has been handed down from generation to generation in the Mori family, and it tells of the importance of everyone working together as one and accumulating all their efforts.

The history of improvement and research by these potters, who had been building up their skills day by day in response to the expectations of users, was passed down to the 15th generation, Shinbei, and now we can hold the kiln in our hands. By knowing the history and background of Hagiyaki, and by using and nurturing Hagiyaki, we may become bearers of history, passing on the dynamism of Hagiyaki to future generations.