Wajima-nuri is one of Japan’s most representative lacquerware crafts. The pieces created by Akito Akagi are admired by many for their sophisticated designs and warm appearance. In 2024, Wajima City in Ishikawa Prefecture, the birthplace of Wajima-nuri, suffered severe damage from the Noto Peninsula Earthquake. Akagi is working to revive and regenerate the region while reflecting on the origins of Wajima-nuri.

Strong and beautiful Wajima lacquerware created through meticulous craftsmanship

Located at the tip of the Noto Peninsula, Wajima City in Ishikawa Prefecture is renowned as the birthplace of Wajima lacquerware. With a history spanning over 500 years, Wajima lacquerware is designated as an Important Intangible Cultural Property of Japan and is celebrated worldwide as a masterpiece of lacquerware.

One of the key features of Wajima-nuri is its exceptional durability. For example, the technique of “nuno-kise” involves applying fabric to the edges of bowls to reinforce vulnerable areas, significantly enhancing durability. Another unique material used in Wajima-nuri is “jino-ko,” a type of ground powder made from diatomaceous earth mined in Wajima. Jinoko is made by burning diatomaceous earth, which is mined in Wajima, into a powder and mixing it with the base lacquer. This meticulous craftsmanship results in Wajima lacquerware that is said to last for over 100 years.

The production process involves 124 distinct steps, each carried out by specialized craftsmen.

Another distinctive feature is the division of labor that supports the 124 processes involved. Specialized craftsmen are responsible for each stage of production, such as the “woodworkers” who shape the wooden bases, the “lacquerers” who apply layers of lacquer, and the “makie artists” who decorate the pieces with gold powder and other materials. This division of labor not only enables efficient production across the entire region but also allows craftsmen to specialize in their respective fields and refine their skills. In this way, the entire town of Wajima functions like a single lacquerware workshop, producing Wajima-nuri of exceptional quality.

Discovering Wajima-nuri and transitioning from editor to lacquer artist

Akagi Akito, a lacquer artisan specializing in Wajima-nuri, handles the final coating process known as “upper coating” while also directing the creation of vessels. His solo exhibitions held across the country are always well-attended. His works are also highly regarded overseas, with pieces collected by the Di Neue Sammlungen Museum in Germany.

Akagi entered the world of Wajima lacquerware in 1988. At the time, he was leading a busy life as an editor in Tokyo when he came across the works of Kado Isaburo, a master craftsman of Wajima lacquerware.

Kadoi was a figure known as both an “outsider” and a “revolutionary” in the world of Wajima lacquerware. He gained recognition early in his career as a Wajima lacquerware artist, winning numerous awards in public competitions. However, he was captivated by the traditional vessels rooted in the lifestyle of Noto and withdrew from public competitions to focus on creating everyday utensils. Kado’s vessels, which constantly questioned the essence of lacquerware, were brimming with vitality, and Akagi was deeply moved by their powerful presence.

Drawn to the charm of Kado’s vessels, Akagi moved to Wajima, apprenticed under a base coat artisan, and learned the techniques.

Creating vessels that harmonize with daily life

What Akagi creates are not vessels for display, but vessels for use. They possess a simple, refined beauty.

“Wajima lacquerware is often associated with glittering works of art, but it was originally a vessel deeply connected to the daily life of Wajima,” says Akagi. ”The true beauty lies in the shapes and colors of vessels that are deeply connected to daily life.” Akagi has always believed this, and during a time when Wajima lacquerware was still used as practical vessels, he created numerous replicas of vessels from the Edo period. What is the beauty and richness that lives in Wajima? Akagi continues to ask himself this question as he pursues the form of vessels.

Project to rebuild the workshop destroyed by an earthquake

The 2024 Noto Peninsula earthquake struck the region famous for its lacquerware, directly affecting the industry. Over 80% of the lacquerware businesses in the area were damaged by the earthquake. Many artisans lost their livelihoods and their places of work, with some forced to close their businesses or evacuate to other parts of the country.

Among the affected artisans was a woodworker who had spent decades alongside Akagi-san, striving to create beautiful forms. He was 86-year-old Mitsuo Ikeda. When Akagi visited Ikeda after the earthquake, his workshop lay in ruins. Ikeda sat motionless in front of the collapsed workshop for two days before losing consciousness and being rushed to the hospital on the third day. “I couldn’t let Ikeda die in despair,” Akagi decided immediately to rebuild the workshop.

“Ikeda-san’s family has been a woodworker in Yoyogi since the Edo period. The beautiful traditional Wajima lacquerware patterns are deeply ingrained in his body. Working with him felt like working alongside his ancestors,” Akagi says. He couldn’t let that skill disappear.

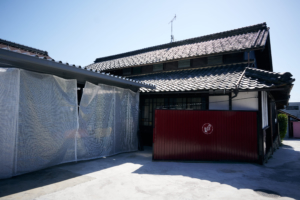

Akagi launched the “Small Woodworker’s Workshop Revival Project,” which garnered widespread support, and the reconstruction of Ikegami’s workshop was completed in just three months after the earthquake. A single light shone in the rubble-strewn town. Ikegami, who had returned from a secondary evacuation center outside the city, rejoiced at the reconstruction of his workshop and began turning wood again.

From one woodworker, the baton was passed to the next generation.

However, since Ikegami-san had no successor, two apprentices from Akagi-san’s workshop were sent to learn woodturning. Ikegami-san was determined to live long enough to see them become skilled craftsmen, but he passed away quietly in July 2024, just a few years after the reconstruction.

After Ikegami’s passing, a wood turner who had once worked on Kaku Eisaburo’s bowls took over the workshop. However, perhaps due to the stress of the disaster, he collapsed after turning 20 bowls and passed away. His son now runs the workshop. He had left his job as a woodworker after the disaster and found work outside the prefecture, but after being persuaded by Akagi, he returned to Wajima to resume his craft. Two apprentices who had been sent from Akagi’s workshop are now striving to master the techniques under their new master. The “small woodworking shop” where Ikegami’s skills and spirit lived on has thus been passed down to the next generation.

Rebuilding the disappearing landscape of Noto

Akagi has also been actively involved in efforts to restore the landscape of Wajima after the earthquake. He had previously operated an auberge and a publishing company in a renovated traditional house in Wajima City, but both buildings were damaged in the earthquake. The damage to the auberge was particularly severe, and it became clear that reconstruction would take a long time. As a result, he decided to repair the publishing company’s building in a coastal village and open a temporary auberge there.

While working on the temporary store in the coastal village, Akagi learned that many of the houses in the village were either completely or partially destroyed and awaiting demolition. While the demolition of completely or partially destroyed buildings is fully funded by public funds, repairs or reconstruction are原則 self-funded. Due to the aging population, depopulation, and many vacant houses in the village, reconstruction is difficult, and many people are forced to apply for public funding for demolition.

The village is characterized by traditional houses with wooden walls adorned with latticework and black tile roofs, creating a unified and beautiful landscape. If public-funded demolition proceeds, this landscape will be lost forever. Akagi decided to purchase two houses surrounding the temporary store and rebuild them in their original form to preserve the historical and cultural value of Noto’s landscape.

Furthermore, he believes that “if we can revitalize this area as a base, it will encourage young people to settle here,” and plans to use these houses as residences for his apprentices and a book café.

As of March 2025, the number of applications for public demolition due to the Noto Peninsula earthquake has reached approximately 38,000 buildings. Among these, there are many buildings that could be repaired and continued to be inhabited. “If we continue with demolition without considering the landscape, the town will become a uniform, characterless area. I hope people will pay more attention to the value of the landscape.” While Akagi-san’s ability to rebuild on his own without public support is limited, he aims to continue spreading awareness of the importance of preserving Noto’s traditional landscape for future generations and expand his efforts.

He aspires to be a ‘pottery shop’ that connects the hometown of Wajima lacquerware to the future.

The work of a lacquer artisan and the restoration of landscapes may seem unrelated at first glance. However, for Akagi-san, they are all part of the same “craftsmanship.” “All things with form eventually break down. That is an inescapable fate. For me, craftsmanship is about continuing to strive against the inevitable breakdown and loss of things. I felt this deeply after experiencing the earthquake.”

Uncovering the lost beauty of traditional Wajima lacquerware, reconstructing the collapsed workshops of woodworkers to preserve their techniques, and reviving the vanishing landscapes of Noto—Mr. Akagi’s “craftsmanship” takes shape through relentless perseverance.

“I’m a potter,” Akagi says. ‘Of course, bowls are vessels, but so are houses where people live. And so are towns where many people gather. Through craftsmanship, I believe my role as a potter is to connect Wajima’s vessels to the future.’ What form will Akagi’s ‘vessels’ take in 50 or 100 years? The story of connecting Wajima’s beautiful vessels will continue onward.