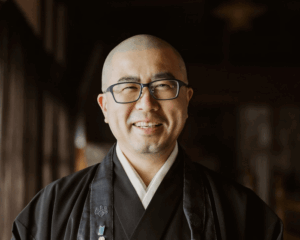

Higashimine Village in Asakura County, which stretches to the east of central Fukuoka Prefecture, is a pottery production area known as Koishiwara Pottery. Zenzo Fukushima, the 16th generation owner of “Chigaiwa Kiln,” which boasts a long history in this area, is a master potter who has been certified as a holder of Important Intangible Cultural Property (Living National Treasure). What is the charm of Mr. Fukushima’s pottery, which continues to pursue new possibilities for Koishiwara-yaki while sticking to local clay and glazes?

Traditions are created and evolved

Surrounded by 1,000-meter-high mountains, about one hour from the center of Fukuoka City, Toho-mura Village in Asakura County, Fukuoka Prefecture, is a beautiful satoyama with abundant nature. The Koishiwara area is blessed with soil suitable for pottery making, trees for kiln fuel, feldspar and straw ash for glaze, and rice and wheat for the raw materials.

Koishiwara Pottery has a variety of traditional techniques, the most representative of which are “tobikanna” and “hakeme. Tobikanna is a technique of applying the edge of a plane to a vessel while turning a potter’s wheel and making regular small cuts to create a pattern, while hakeme, as the name implies, is a technique of drawing a pattern with a brush while turning a potter’s wheel. Both of these techniques give a simple and warm atmosphere, and many of Koishiwara’s kilns use this technique to produce miscellaneous daily-life ware.

Feeling a sense of crisis in the age of quantity over quality, Koishiwara is seeking a new style of pottery making.

Fukushima’s gallery is not filled with so-called typical Koishiwara Pottery. Many of his celadon porcelain pieces are clothed in a unique blue color, and the beauty of their shapes and soft, transparent hues will make you wonder, “Is this Koishiwara-yaki, too? The birth of these styles was the result of Fukushima’s long and challenging years.

Since he was a child, Mr. Fukushima’s playground was the workshop where his grandfather, father, and other craftsmen turned the potter’s wheels. Since he had decided to take over the family business as a child, he traveled around the country during his college days to see other famous production areas. However, after visiting many production centers, he was reminded of “the high level of Koishiwara’s roku-roku technology. He decided to learn in his hometown, and after returning to his hometown, he worked hard at his apprenticeship, making 200 teacups and 100 sake cups in a single day.

At the time, the demand for folk art ceramics for daily use was rapidly increasing due to the growing folk art movement. Of course, the Kyushu region was no exception. Koishiwara-yaki, which was durable, simple, and easy to incorporate into daily life, was widely accepted by consumers, and the more it was made, the more it sold.

The number of pottery studios, of which there were only nine when Mr. Fukushima was a child, increased to nearly 30, but at the same time, price competition was beginning to outweigh quality. Concerned about this situation, Mr. Fukushima began to search for a new style of Koishiwara-yaki pottery that only he could make.

To the Prefectural Exhibition and the Japan Traditional Crafts Exhibition

The first thing he set out to do was to study glazes. Using Koishiwara clay, which has a high iron content and shrinks significantly during firing, and glazes made from local ingredients, he repeatedly made prototypes using traditional Koishiwara pottery techniques under the theme of how to create works that were uniquely his own. He repeated trial productions using the traditional Koishiwara pottery technique. It won a prize.

However, when visiting Fukuoka City, the venue for the prefectural exhibition, he stopped by the Japan Traditional Crafts Exhibition, the largest public exhibition of traditional Japanese crafts in Japan, and was shocked.

I didn’t realize how different the level of craftsmanship was,” he said.

That was the start of a new challenge for Mr. Fukushima. He read the catalog of the Japan Traditional Crafts Exhibition so thoroughly that he memorized it. For Mr. Fukushima, who was taking on the challenge of creating a new style of work that no one else in Koishiwara had ever produced, the catalog was his mentor.

While imagining the work he wanted to create, he went through endless trial-and-error, combining “clay x glaze x firing temperature” and “time x cooling time. Just around that time, excavation of the oldest kiln in Koishiwara, dating back to 1682, began, and many items were unearthed that would be unthinkable from today’s Koishiwara pottery, such as porcelain and tea utensils in underglaze blue. At that time, Koishiwara was under the patronage of the Fukuoka domain and produced a wide variety of pottery for the lord.

Witnessing these excavated items, Mr. Fukushima said, “Skipping planes and brush marks are techniques that were born in the Showa period, and are only a small part of Koishiwara Pottery’s 300-year history. My challenges may be called “tradition” in the Koishiwara of the future. I decided to believe in myself without being swayed by the voices of others.

Creating celadon that can only be made in Koishiwara

Thus, Mr. Fukushima began to produce celadon porcelain with a transparent appearance that is at odds with the rugged atmosphere of traditional Koishiwara pottery.

Koishiwara clay is difficult to handle because of its high iron content, but I want to turn this disadvantage into an advantage and create celadon that can only be made here,” he said. The celadon he produced was named “Nakano Tsukihakuji,” a combination of Nakano, the ancient name of the area where the kiln is located, and the beautiful color of the celadon, and has become one of Mr. Fukushima’s representative works. The soft, gentle blue color of this work, which was fired by applying a blue-white glaze called “Tsukihaku-glaze” to the Koishiwara clay, which is black with high iron content, immediately captured the hearts of those who saw it. The black edges were scraped off to bring out the original clay color, and one of the characteristics of the piece is that it retains the smell of Koishiwara pottery.

This piece was first exhibited at the 60th Japan Traditional Crafts Exhibition. At the time, some in the craft world questioned whether Koishiwara-yaki could be called Koishiwara-yaki because of the absence of the hopping plane and brush pattern. However, Mr. Fukushima replied, “This is genuine Koishiwara-yaki because we used all local materials, turned the potter’s wheel, applied glaze, and fired it in Koishiwara. He exhibited with confidence, saying, “If we do not continue to challenge ourselves with new styles, the traditions of the next generation will not be born.

For the next 10 years, he continued to exhibit his works while expanding the possibilities of expression of Tsukihaku-zashi by changing the shape and the way the porcelain was pierced every year. As a result, the beauty of Tsukihaku-zashi was recognized by experts who were initially surprised, and he received the Prince Takamatsu Memorial Prize at the 70th Japan Traditional Crafts Exhibition.

In order to express his one-of-a-kind worldview, Mr. Fukushima carries out all processes by himself, from clay and glaze making to wheel spinning and firing. He laughs, “If you compare the artists at a kiln, where the division of labor is still advanced, to the conductor of an orchestra, I am a singer-songwriter.

Recognition as Living National Treasure Encourages Disaster Victims

In July 2017, torrential rains in northern Kyushu hit Koishiwara, and of the 42 pottery studios in the area, 11 were damaged by mudslides and other disasters, casting a dark shadow over the whole district. Two weeks later, the disaster-stricken area received the bright news that Fukushima had been recognized as a “living national treasure” at the young age of 57.

“To be honest, I didn’t think I would be able to become a living national treasure for Koishiwara ware, and I also wondered whether it was appropriate to be happy at a time when the region was going through such a difficult time, but I also felt that it was extremely gratifying for the development of Koishiwara ware,” said Mr. Fukushima.

The news gave a great boost to the people involved in Koishiwara ware. Following Mr. Fukushima’s designation as a Living National Treasure, there was an increase in the number of young people who wanted to create new works without being bound by existing techniques. In addition, the flooding led to Koishiwara ware receiving nationwide attention, and the region began to enjoy a tailwind as a production center, bringing vitality to the area.

“I see my designation as a Living National Treasure in my 50s as a sign that I should take on more challenges in my future as an artist. There is a lot of pressure, and it’s not easy. I still make mistakes every day. But I believe that learning from your mistakes is the most important thing, and that is for sure.

Fukushima says that being given the honor of being a living national treasure has made him even more motivated to create.

His works convey the message that tradition is not just something to be protected, but also something that can be created anew.

We can’t wait to see what kind of Koishiwara tradition will be born from his hands in the future.