Long ago in snowy Aomori, cotton cultivation was difficult, so cloth was used with great care. Worn-out kimonos were eventually cut into strips and woven on a floor loom to make work clothes and other items. This later became known as Nanbu Saki-ori. Teruko Kobayashi carries on the founder’s vision and is striving to spread the appeal of Nanbu Saki-ori in the Reiwa era.

What is Nanbu Saki-ori?

The historical background of Nanbu Saki-ori, truly unique to this land

Born from the wisdom of women who cherished their possessions, Nanbu Saki-ori boasts a tradition spanning over 200 years, tracing its history back to the Edo period.In snowy Aomori, cotton was difficult to grow. Cotton and old cotton cloth transported by Kitamae ships were extremely precious, so farmers at that time wove the natural fiber hemp they cultivated into cloth for clothing. They didn’t discard scraps either; they layered them for sashiko stitching or, finally, tore them and joined them to create a single piece of cloth. This was the prototype of Nanbu Saki-ori.

When the railway opened in 1893, worn cotton fabrics began circulating in this region. Farmers started weaving them on floor looms, using threads from unraveled hemp sacks as warp threads and thin strips of worn cloth as weft threads.The thick, coarse-textured saki-ori weave was well-suited to this region’s harsh, cold winds and was used for work clothes and kotatsu covers. “In this way,” Kobayashi explained, “the people of this area have lived by devising various ingenious methods to overcome the cold.”

Diverse yet each a one-of-a-kind piece

Despite being a very simple weave—”hemp yarn and old cotton shredded into strips about 1 cm wide woven on a floor loom”—the variety of weaving techniques is by no means limited.The most basic plain weave, the saguri weave where cloth and thread are interwoven alternately, the ichimatsu weave and ajiro weave created by warping two colors of thread, the interesting diagonal pattern of the hikikaeshi weave, the tsuzure weave that creates patterns within the fabric, and many other variations exist.

Today, while utilizing traditional techniques on floor looms, it’s possible to create a wide range of items suited to modern life—such as vibrant kotatsu covers, tote bags, bedspreads, tapestries, and slippers.

One of the major charms of Nanbu Saki-ori is that “you can create original items found nowhere else in the world.” “Even if you use the same fabric, the texture changes completely depending on when you weave it in and how much force you apply while weaving,” laughs Kobayashi. “Even if you try to make the same thing, you can never make it twice.” This is why each piece of Nanbu Saki-ori is said to be one-of-a-kind.

The Beginnings of the Nanbu Sashiko Preservation Society: A Miraculous Encounter

It all started when Kobayashi’s sister, Eiko Kanno, then 35 years old in 1971, attended the distribution of her beloved aunt’s belongings.A purple sash made of split weave lay in a corner of the room, seemingly worn out and unwanted. Yet Kanno was deeply drawn to its rich color and the meticulous texture of its weave. “If no one wants it…” she thought, and took it home. The more she looked at that sash, the more captivated she became by the warm, handwoven character of the fabric, and she grew increasingly eager to learn about split weaving.

However, by that time, Nanbu Sashiori was already on the verge of extinction, as people considered “weaving worn-out clothes and rags shameful.” Persistently searching for someone who could teach her its roots and techniques, she eventually found Ms. Kiyé Higashiyama and Ms. Mise Akasaka in Towada Lake Town the following year.Both women initially refused, telling her, “You won’t earn a single penny doing rag weaving,” but through her sincere and repeated visits, she finally gained permission to learn.

A Life Devoted to Nanbu Saki-ori with Burning Passion

Kanno-san reevaluated the value of Nanbu Saki-ori, learned its techniques and spirit to become an inheritor herself, and established the Nanbu Saki-ori Preservation Society on July 7, 1975, Tanabata Day. She started a “Saki-ori Classroom” at her home, pouring her heart and soul into promoting the weaving. Her contributions were highly recognized, earning her the title of “Aomori Prefecture Traditional Craftsman” and many other honors.

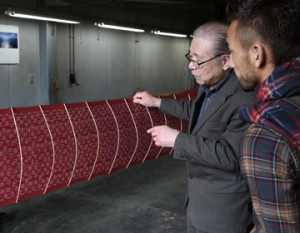

Driven by his desire to “introduce Nanbu Saki-ori to as many people as possible,” he lobbied Towada City for years. His efforts culminated in 2002 with the opening of the Towada City facility, the Master Craftsman Workshop “Nanbu Saki-ori no Sato,” adjacent to the Towada Pia Roadside Station.The sight of about 75 looms lined up is spectacular, most of which were collected by Ms. Kanno. “She gathered them not only within Towada City and the Nanbu region, but also traveled to places like Fukushima Prefecture whenever she heard about them,” Mr. Kobayashi told us, gazing fondly at the looms.

After successfully organizing the Nanbu Saki-ori Festival in Towada in October 2003 to commemorate the 30th anniversary of the preservation society’s founding, Kanno passed away in March 2004. He had been suffering from cancer but kept it hidden until the very end. He was 67 years old.

Sister Carries On the Legacy

Kobayashi-san explained that in an era when weaving rags was considered shameful, she initially faced social disapproval and was against Nanbu Sakiori. However, about ten years after Sugano-san began working with Nanbu Sakiori, Kobayashi-san tried it herself on a whim and was immediately captivated. “Sitting at the loom, touching the fabric, and weaving was truly enjoyable. It was a real healing experience for me, who was exhausted at the time.Before I knew it, working until 1 or 2 in the morning became normal. That’s when I truly began to take Nanbu Saki-ori seriously,” Kobayashi says with a smile.

Today, the Nanbu Sashiko Preservation Society has 130 members, most of whom are housewives. While women face various worries and hardships, like raising children, the society strives to embody the founder’s vision: “Leave all that behind when you come here.” They make every effort to ensure no one accumulates stress while participating.About 50 students attend the weekly Wednesday classes, which have no set start or end times. The group gets along so well that laughter is constant. They work to complete one item per year for the city’s cultural festival, ensuring everyone can submit their work.

Beyond the regular classes, they offer experiences, attracting many foreign visitors and groups of children and students. “It seems especially fresh for the kids; they weave with such enjoyment,” Ms. Kobayashi says, her eyes crinkling. She recalls one child who came for an experience and then pleaded, “Daddy, I want this loom. Please buy it for me.” The number of people who have experienced weaving here has surpassed 11,000.

Preserving the Founder’s Vision for Nanbu Saki-ori

The used cloth used for the weft threads comes from donations nationwide, including yukata from hotels and inns, and even sumo stables. “Some people send us cloth, saying, ‘My grandmother passed away,’ or ‘My mother passed away,’ but it feels wasteful to throw it away, so could you take it?'” says Kobayashi. “That’s why we’re supported by everyone.”

While Kobayashi wishes to spread Nanbu Sashiko with this widespread support, he also states, “This isn’t a facility for training artists. Passing on sashiko to future generations and keeping it alive is the most important thing.”Back when Ms. Kanno was still running the workshop, other municipalities with growing numbers of enthusiasts apparently offered, “We want to hold a contest. Please plan it and judge it for us.” However, Ms. Kobayashi firmly refused, believing that裂織 is absolutely not something to be competitive about. “裂織 isn’t about competition,” Ms. Kobayashi told us. “Everyone is a first-place winner. You should just do it freely, following your own sensibilities. That’s one of the strong convictions I inherited from my sister.”

The Society’s Half-Century Journey and Future Initiatives

In 2025, the Nanbu Saki-ori Preservation Society will celebrate its 50th anniversary. As part of the commemorative events, themed “Connecting to the Next Generation,” they are holding a commemorative exhibition and free hands-on sessions. They are showcasing over 500 pieces demonstrating the inherited techniques, displaying a 50-meter-long woven fabric created collaboratively across all their classrooms, and attempting various other challenges.Driven by the belief that “Nanbu Sashiko is a cultural treasure our region can be proud of and has the potential to become a future local industry,” the association is producing and selling not only traditional pieces but also sashiko designs suited to modern tastes. They even received an order from a Japanese designer living in France for indigo-dyed sashiko fabric to be used in men’s suits.

“Nowadays, everything runs on electricity with the push of a button. I feel it’s essential to teach children that, just like in the past, their own hands and feet can be the energy to create things.The reason Nanbu裂織 remains timeless is probably because everyone shares that feeling of cherishing things. My mission is to make more people aware of it,” says Kobayashi. Carrying on the tradition of Nanbu裂織 and the founder’s vision, and striving to create a society where everyone has a place, Kobayashi and her team continue weaving today. They weave, one step at a time, using colorful warp threads and strips of fabric as weft threads.