In Ichikawa Misato Town in southwestern Yamanashi Prefecture, where the Fuji River, one of the three most rapid rivers in Japan, flows, industries such as “Wabishi” (handmade Japanese paper) and “rokugo no insho” (seal) have developed since long ago. One of these industries is “Ichikawa Hanabi,” which has fascinated fireworks master Gen Sasaki. What is the creator’s passion behind “Wabi,” a traditional technique passed down from generation to generation, which lights up the world with a new light?

Fireworks Town, Ichikawa Misato

Ichikawa Misato’s fireworks industry is said to have originated from the Takeda clan’s military “wolf smoke” technology, which was used in the Warring States period. The largest fireworks display in the prefecture, “Shinmei no Hanabi,” held every August, attracts many tourists who come to see the spectacular night sky decorated with some 20,000 shots of fireworks produced by long-established local fireworks companies. In this town of fireworks, Mr. Sasaki specializes in “Japanese fireworks,” which have long been produced only in Japan. Currently, “Western-style fireworks,” which use chemicals imported after the Meiji Restoration and produce colorful colors through a combination of flame reactions, are the mainstream, but “I was fascinated by the traditional Japanese lights that have been handed down since the Edo period,” he says.

Traditional Japanese Fireworks “Wahi

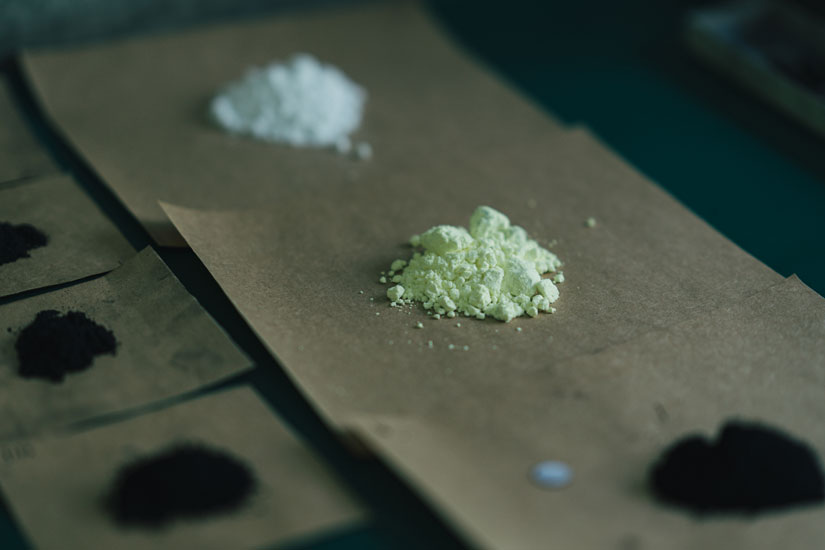

The raw materials of Wahi are only natural materials such as charcoal, gunpowder, and sulfur, all of which can be obtained in Japan. Although not flashy or showy, the delicate shades of red and orange in the charcoal’s original reddish-brown color give the fireworks an air of Japanese “iki” (style). At fireworks festivals, Japanese-style fireworks are often set off between the gorgeous Western-style fireworks. He has been working for a long-established fireworks company in Yamanashi for six years, learning everything from launching to manufacturing fireworks, but since becoming independent, he has taken on the title of “wagi-shi,” and is now involved in a wide range of activities both in Japan and abroad.

What is the purpose of making and launching fireworks?

Sasaki says he has had a yearning for a traditional Japanese occupation since he was a university student. When he came across a movie titled “Heaven’s Bookstore: Love Fire,” he was fascinated by the sight of a pyrotechnician setting off fireworks for his lover in heaven, and decided to pursue a career in the field of fireworks. After graduation, he contacted and joined a well-established fireworks company in Ichikawa Misato Town, which he found particularly attractive among the fireworks launched by fireworks companies nationwide. Leaving his hometown of Saitama Prefecture, he learned the entire process of making and launching Western-style fireworks. While devoting himself to making fireworks, he achieved a second place finish at the 2012 Omagari Fireworks, a competition held in Akita Prefecture, which is renowned as one of the three largest fireworks festivals in Japan. While he was delighted to be recognized for his advanced techniques and ideas, he also asked himself, “For what purpose do I make and shoot fireworks?

Becoming a “Japanese pyrotechnician” instead of a pyrotechnician

The Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011 triggered a conflict in his activities. He could only mourn the horrific situation in the affected areas from afar, and the helplessness of not being able to do anything as a pyrotechnician has always stuck with him. He re-learned about fireworks again and wondered if there was any way he could launch fireworks that would be meaningful to society. He learned that fireworks have been used since ancient times for prayers, such as “memorial services,” “repose of souls,” and “dedication. I learned that the origin of fireworks is that they were set off to pray for the souls of the dead, for the repose of souls, and for votive offerings. For example, the Sumida River Fireworks Festival, which has become a summer tradition in Tokyo, is said to have originated from the Ryogoku River Festival held in 1733. It began when fireworks were set off on the day of the river opening, the first day of the noryo period, as a memorial to those who died in the famine and epidemic of the Kyouho period and as a prayer for the removal of calamities. In addition, the ancient Japanese custom of paying homage to gods and Buddha, ancestors, and the bounty of nature has been passed down in the dedication fireworks. The Japanese firework was filled with such prayers for peace and gratitude. In 2014, Sasaki became an independent Japanese firework artist and started his own business.

The desire to set off fireworks not for self-satisfaction, but to bring joy to others, was the driving force that pushed me forward.

Establishment of the Japanese firework brand “MARUYA

The first thing he did after becoming independent was to launch “MARUYA,” a brand specializing in Japanese-style fireworks. Starting with “toy” handheld fireworks such as senko-hanabi (sparklers), he gradually expanded the scope of his production to include small fireworks called teien-hanabi (garden fireworks), fountain fireworks, and fireworks for launching. The company has been working on various forms of expression of Japanese firework regardless of the type of fireworks it produces.

Mr. Sasaki says, “I start by going into nature and obtaining materials such as charcoal and sulfur, which are used as raw materials. He says, “I go into nature to obtain raw materials such as charcoal and sulfur.” The selection of wood is the most important process in making wahi, which expresses the true color of charcoal fire.

The Appeal of Charcoal in Japanese-style Fire

Pine wood is the most commonly used material for making wagibi. For example, paulownia charcoal is a reddish orange color, and the color of the sparks varies depending on the characteristics of the wood. This is related to the combustion temperature: the lower the temperature, the more reddish, and the higher the temperature, the more yellowish.

The expression also varies depending on the grain size of the charcoal. In fireworks, before forming the spherical gunpowder called a “star,” the charcoal is sifted once to make it into a powder. This process is said to create a difference in the degree of burning when the tinder is ejected. Coarse-grained charcoal leaves a slow burning ember, while fine-grained charcoal extinguishes quickly. By combining powdered charcoal with other raw materials such as potassium nitrate and sulfur and devising the mixing ratio, the color and the combustion of gunpowder can be made stronger or weaker, producing subtle colors.

The Japanese firework, which requires precise balancing, is filled with the wisdom and techniques of fireworks makers from the olden days, and if you look at an old blending book, you will find that the blending patterns are so subtle that you may overlook the differences. The depth of the firework is because it uses only reddish-brown colors,” says Sasaki.

Fire of Prayer

In addition to the manufacture of Japanese fireworks, there is the “inoribi” project. It means “prayer fire,” a firework that contains prayers for the repose of souls and the repose of souls, and it travels to various places to offer prayers for the repose of souls and the repose of souls of those who have suffered from natural disasters and wars. The first such event was the “Kofu Air Raid Memorial Fireworks” held in July 2020 to pray for the repose of the coronavirus and to exorcise the evil spirits. The theme was “to feel the sound, vibration, and lights, and to offer prayers. The Japanese fire for the repose of the soul is called “Kiku-gata,” which imitates a chrysanthemum, and on the day, 10 Japanese fires were launched alternately with silence in a slow pause. As they gradually expand their activities to include fireworks for the repose of souls in Okinawa and Chiran and votive fireworks at festivals in various regions, the number of local collaborators who support their efforts is increasing.

Believing in the Power of Japanese Fireworks

In 2022, a long-desired fireworks factory will be completed in Ichikawa Misato Town. Mr. Sasaki looks back on the eight years until then as a series of hardships. When he decided to start his own business specializing in Japanese-style fires in an industry dominated by Western-style fires, many people around him were concerned about demand, and he was often told by his peers that he could not do business only with Japanese-style fires. In the face of adversity, he continued his own research, starting with the basic sparklers, and it was only when he obtained a license to manufacture fireworks that he felt he had “finally made it to the starting line.

I was convinced that WA-HI was a firework with the power to make people happy,” he said. Perhaps it was my strong belief in myself and my determination to keep going that led me to this point.

Spreading the Spirit of Japan to the World

Mr. Sasaki’s future prospects are focused on activities in accordance with two themes. First, to “convey Japanese spirituality and culture through Japanese fire,” he will hold events where people can fully enjoy Japanese culture, and use Japanese fire as a stage for such events. Currently, he gives lectures at educational institutions and cultural events, and holds workshops on making sparklers, but he is eager to expand the scale of his events. Another indispensable activity is that of “inoribi. He said, “From now on, I would like to go around the world, not only to Japan, to shoot fireworks to pray for the souls of the dead, the repose of souls, and peace.

I think the road is not that long. If you have a strong desire, you will meet various people, and that will be a good opportunity for you. That is the one thing I want to keep in mind as I move forward.

Traditional fireworks continue to be lit in the modern age

The shading of the charcoal fire, the intensity of the sparks and how they remain. My goal is to create a world view by using these expressions.

The reddish-brown fire that lights up the night sky today is made using a process that has not changed since the Edo period. How many people know about the prayers and history behind it? As a bearer of wahi and an inheritor of the culture, he says, “You can fully feel the charm of wahi not only with fireworks, but also with sparklers. I would like to express the spirituality of the Japanese people with forms of wagashi that suit the time and place,” says Mr. Sasaki, a wagashi master. The day is not far off when his challenge and unwavering faith will bear fruit.